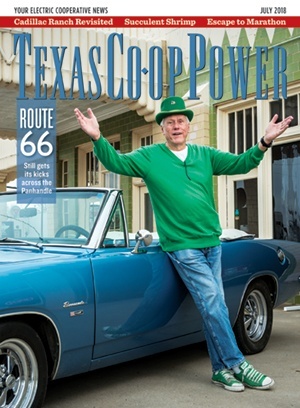

Rufus Duncan doesn’t fish, hunt or golf. For outdoor recreation, he walks in the woods. But not just any woods—a short drive from his Lufkin home, Duncan retreats to his family’s 1,885-acre property in Newton County, part of an area known as Scrappin’ Valley. For Duncan, you might as well call the place heaven.

Hills of native grasses and myriad other plants roll across a savanna lorded over by soaring longleaf pines.

“It’s absolutely the prettiest place in the woods to walk,” he says about the property, where he’s building a weekend getaway.

Scrappin’ Valley is not, however, just a walk in the woods. It comprises a critical part of Longleaf Ridge, a longleaf pine habitat spanning five counties. Some 100,000 acres of the sandy upland lies within Angelina and Sabine national forests. Another 300,000 acres sit on adjacent private property. The U.S. Forest Service says this 27-mile-long high-wooded corridor has “the best examples of longleaf pine ecosystems in Texas.”

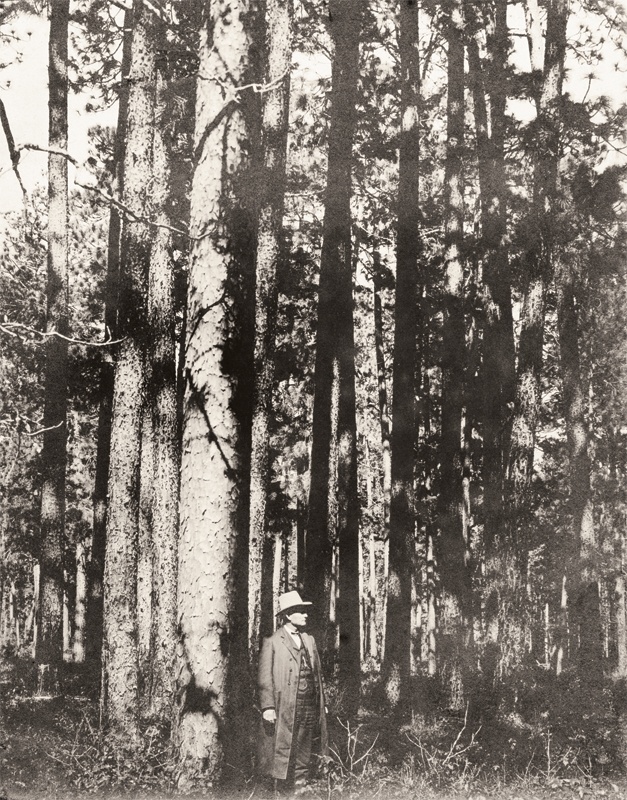

For centuries, such longleaf-dominated forests blanketed up to 90 million acres of Southern coastal land, from East Texas to Virginia. Native Americans hunted game from the open forest floor and wove coiled baskets from long pine needles. Anglo-American settlers, heading west during the 19th century, drove wagons through longleaf forests that looked more like parks than today’s typical brush-and-vine thicket.

From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, some 97 percent of old-growth longleaf trees were clear-cut for their high-quality lumber. Now, some East Texans want to turn back the hands of time. A growing list of private landowners, such as Duncan, are joining forces with government agencies and conservation groups to bring back the longleaf. Public and private partnerships offer a path to a successful return of our historic landscape.

Duncan credits the late East Texas timber baron and conservation pioneer Arthur Temple Jr. with saving Scrappin’ Valley, a critical part of the original forest.

“Early on, he understood the value of native species and environmental responsibility,” says Duncan, CEO of Higginbotham Brothers building supply stores. “The Temple family saved a lot of native East Texas.”

World-Class Biodiversity

The longleaf forest comprises one of the most species-rich ecosystems outside the tropics, the U.S. Forest Service noted in a 2010 proposal for longleaf restoration in Texas. Mature longleaf pines rise 100 feet or more to form a shady canopy above an interconnected community of plants and animals below. Arrayed in a parklike savanna, the understory features hundreds of species of plants—from small trees and native grasses to varied herbaceous plants and even carnivorous plants that digest insects. A longleaf forest supports healthy populations of white-tailed deer, quail, wild turkey and small game. Historically, black bears also called it home.

The habitat also nurtures dozens of species of birds, including federally protected red-cockaded woodpeckers. Indeed, government agencies and environmental groups have worked for years to restore longleaf forests as a way to save rare and endangered species, explains Kent Evans, coordinator of the Texas Longleaf Implementation Team, a public-private partnership promoting longleaf restoration. As beautiful as it is, the iconic longleaf forest is worth restoring for practical reasons as well, adds Evans. Harvested longleaf pine brings top dollar to timber producers, especially in the utility pole market.

Longleaf also lives longer and is hardier than other pines. It’s resistant to southern pine beetle infestations that devastate other pine species. It’s also more resistant to storm and hurricane damage because of its deeper taproot. Timber growers are learning that longleaf pines thrive on poor sandy soil where other pines struggle, Evans says. “There’s also a promising market in Texas for selling longleaf pine straw to the nursery trade,” he adds.

Most importantly, longleaf pines are highly resistant to wildfire. “When a big wildfire destroys a typical pine plantation,” Evans says, “growers get interested in adding longleaf to decrease risk and improve the bottom line.”

Prescription for Fire

Though longleaf pines are pyrophytic (fire resistant), their very survival requires periodic fires. Lightning fires and fires set by Native Americans and early settlers helped eliminate competing trees that were less fire resistant. This promoted the slow-growing longleaf pines.

After longleaf pines were clear-cut, tree farms were replanted by the 1930s with loblolly and other faster-growing pines. Fire suppression became the norm, limiting natural longleaf regrowth.

“People changed the native ecosystem before, and now we’re trying to change it back by reintroducing fire into the forest,” says Shawn Benedict, manager of the 5,654-acre Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary, part of the Nature Conservancy. The sanctuary focuses on the longleaf ecosystem, but also supports native loblolly and shortleaf pines. Sandy soil, as deep as 40 feet, slopes toward the serpentine Village Creek. The mix of upland and riparian terrain protects an astounding 582 plant species (including 340 kinds of wildflowers) and 234 animal species. Benedict and his team ignite longleaf areas every two years or so, burning the understory 50–500 acres at a time, mostly in spring and summer.

Such frequent, low-intensity fires control invasive and unwanted plants and insects while removing excess woody plants from the forest floor. “More prescribed burns results in less wildfires,” Benedict says.

Prescribed burns also add nutrients to the ground, allowing a gradual, natural return to the historic longleaf savanna. The goal, Benedict says, is maximum biodiversity.

At any mention of biodiversity in East Texas, many think of Big Thicket National Preserve, part of the National Park Service. Known as the biological crossroads of North America, the preserve encompasses 100,000-plus acres of land and water spanning seven southeast Texas counties. Honored by the United Nations as a “Man and Biosphere Reserve,” the preserve has experimented for decades with prescribed burns, says preserve biologist Andrew J. Bennett. In 2000, the preserve got serious.

“We began using more intensive treatments, including mechanical brush removal, herbicides and planting longleaf pine seedlings in addition to prescribed fire,” Bennett says.

The intensive approach continues today, expanding by 50 acres each year. To commemorate the centennial of the National Park Service two years ago, the preserve cleared several hundred acres and enlisted volunteers to plant 100,000 longleaf seedlings. Every winter, the preserve works with the National Parks Conservation Association and other volunteer groups to plant more longleaf pines.

“The ultimate goal,” Bennett says, “is to restore longleaf to its historical range, which likely would include several thousand more acres across the preserve.”

The four national forests of Texas (Angelina, Sabine, Sam Houston and Davy Crockett) have spent decades working to turn 25,000–30,000 acres into high-quality longleaf pine forest.

The U.S. Forest Service believes more longleaf forests are possible—perhaps 200,000–250,000 acres, or one-third of Texas’ national forests. The service hopes to reach this goal in the next 20 years. That’s the Lone Star State’s contribution to a national plan set forth in 2010 to increase longleaf pine acreage from 3 or 4 million acres to 8 million acres.

To attain that goal, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, seeks help from rural landowners by offering financial assistance for planting longleaf pines, conducting prescribed burns and controlling invasive plants. To apply, contact a local USDA service center.

In 1886, East Texas boasted nearly 3 million acres of longleaf pine forest. Just over a century later—about the time it takes a longleaf seedling to reach maturity—only 45,000 acres remained. While the longleaf no longer dominates the forests of southeast Texas, there’s hope that ongoing restoration will safeguard the majestic tree as an important touchstone of our natural heritage.

“We are learning more about the longleaf all the time,” says Evans, the Texas Longleaf Taskforce coordinator. “Its range across East Texas may have once extended farther than we have thought. These are clues that really get you excited about the future.”

Long Live the Longleaf

Experience a longleaf pine forest at the following locations, as suggested by the Texas Longleaf Taskforce, an alliance of landowners, organizations and agencies.

Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary (4208 Highway 327 W. near Silsbee) offers 6.5 miles of trails through longleaf pines and associated habitat along Village Creek. Owned by the Nature Conservancy, the site features a small parking lot and trail information at the entrance. Admission is free, and the sanctuary is open daily, sunrise to sunset. Call (409) 658-2888 or visit nature.org/texas.

Big Thicket National Preserve, part of the National Park Service, features longleaf ecosystems via hiking trails, notably the Sandhill Loop Trail in the Turkey Creek Unit and the west side of Turkey Creek Trail near the trailhead at FM 1943. The Pitcher Plant and Sundew trails mix longleaf pines and carnivorous plants. The preserve’s best longleaf habitat is off a trail on the north side of Lilly Road near the intersection with FM 1276 in the Big Sandy Creek Unit. The preserve is always open, free of charge, to foot traffic. For maps, check the visitor center north of Kountze at 6102 FM 420, off U.S. 69/287. Find out more about guided tours and events by calling (409) 951-6700 or visiting nps.gov/bith. To volunteer for restoration projects, call (409) 951-6725.

Watson Rare Native Plant Preserve lies a short drive north of the Big Thicket office at 527 CR 4777 near Warren. Located in the Lake Hyatt Estates subdivision off U.S. Highway 69/287, the 6-acre site features a walking trail through longleaf pines beside a small lake. Once the home of the late conservationist Geraldine Watson, the preserve is open to the public at no charge, sunrise to sunset, daily. The site has no restrooms. Visit watsonpreserve.org for more information.

The National Forests and Grasslands of Texas, an agency of the U.S. Forest Service, operates Boykin Springs Recreational Area.

The Sawmill Hiking Trail meanders 5.5 miles through longleaf savanna to Bouton Lake. Take Highway 63 east from Zavalla for 10.5 miles, turn south on Forest Service Road 313, and go 2.5 miles to the Boykin Springs campground. Day use is free; it’s $6 per day per site for camping. For more info, call (936) 897-1068 or go to fs.fed.us and search by state and forest.