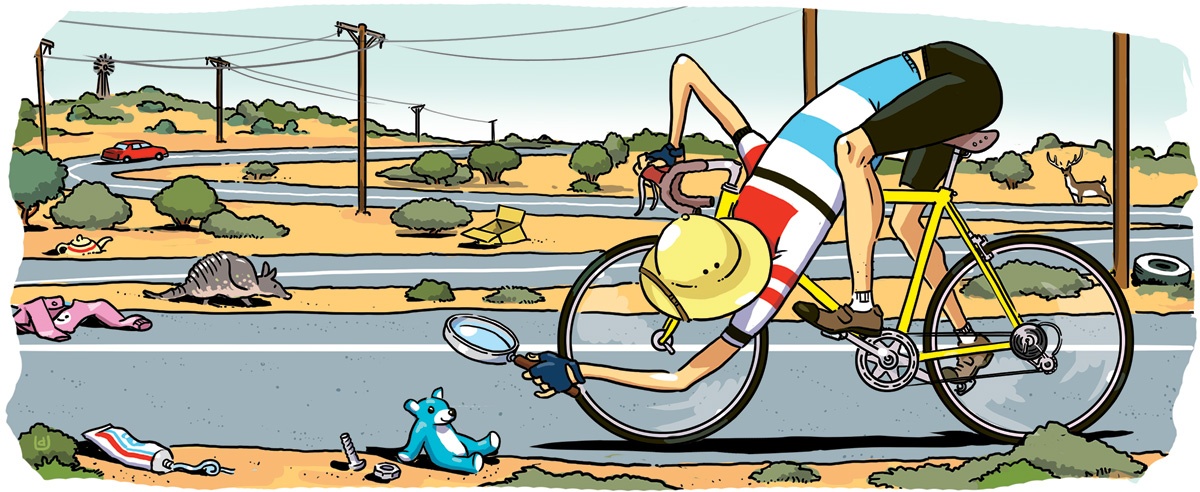

For most travelers, most of the time, the world is the width of a windshield. They tend to look only where they are going: ahead. But for me, the highway is a horizon, the same each day but always different. It’s not going anywhere, nor am I, not much. If a driver is a sailor, lately I’ve become a beachcomber.

My shoreline is Texas Ranch Road 674, a 56-mile scribble of asphalt snaking from the cedar-sucked plateau of Rocksprings, southward along the flash-flooded canyons, breaks and washes of the West Nueces headwaters, to the thorny flats of Brackettville. It is unexpectedly stunning terrain—mind you, no country even for old goats, not since the mohair subsidy went away and the last prayer of topsoil (what little there was before overgrazing) abdicated to limestone. It’s still livable, however, for armadillos, ringtails, red-tails, turkeys, turkey vultures, anything with antlers, and, as uploaded onto YouTube from the webcams of the hunters who give the local economy its last shot, the occasional mountain lion and bear.

By my informal count, RR 674 is disturbed by barely 100 cars a day. I don’t drive it much myself. Mostly I prefer to cruise my coast on foot or by bicycle. I know some of this road better than the shoulder surgeons of the Texas Department of Transportation; better than the school bus driver who faithfully rumbles 25 miles each way, each school day, to pick up and drop off one solitary kid; better than the FedEx guy who moans that he loses money driving it and pleads to leave packages at the feed store in town; better than the Border Patrol agents who hardly bat an eye when they spot me inspecting the guard-rails, collecting castoff nuts and bolts in a blue Ikea bag.

Some insist that life is about the journey, not the destination. Perhaps so, but, for the sake of discussion, let’s say it’s neither. A highway need not be a funnel, as it is for so many, with its rhinestone reflectors beckoning toward the pinhole of oblivion. My highway is a belt laid longwise, cinching me to terra firmly. From my porch, with an easy turn of the head, I can survey a good mile of it. When a weekending airman from the base in Del Rio rockets his motorcycle through the roller coaster of low-water crossings, cattle guards and “falling rock” warnings, I hear his engine keening, far then fierce then faint again, like a wasp across a window screen. What I’m saying is: There is On the Road, and there is on the road. Right now I’m all about lowercase. The wide angle is what grounds me.

I am reminded of The Gods Must Be Crazy, the movie about the African who treks to the end of his known world to throw a Coke bottle off it. Perhaps that would explain the preponderance of Coke bottles and cans—not to mention the Huggies, Big Gulps and at least one Neiman-Marcus Last Call shopping bag—that now decorate my viewshed. Evidently, for some people, where I live is the end of the world. A comforting thought, actually. And even if the jetsam I happen upon during my daily jaunts is unsightly and of negative worth, it’s junk that gives measure to an otherwise anarchic landscape. As with the jar dropped so famously by the poet Wallace Stevens, “The wilderness rose up to it.” In the interest of further clarity, I report that on RR 674, the preferred beer of litterers is Coors Light.

One Christmas morning, my wife and I set out on a bike ride to Kickapoo Cavern State Park, 11 miles south of our gate. There is much to appreciate along the way: two state historical markers to the early settlers of the Nueces’ west “prong,” whose patriarch is commemorated for his diverse but perhaps complementary talents of doctoring and coffin-making; a homemade cross marking a pullout where, several years ago, an unhappy woman took pills and then her life by driving over the bluff, not to be discovered for days; and a massive rock face over which the highway climbs between Newberry and Four Mile draws, affording a magnificent panorama of battered hills and dry river bed that might make lunar travel redundant.

It is here on the big climb where I have done my most fruitful guardrail scavenging. One afternoon, concentrating on a 1-mile span, I picked up 160 heavy bolts and 67 nuts discarded by the crew that replaced the rail. Initially, I had paused only to pry up a nasty roofing nail that for months had been sticking up from the southbound lane and was threatening one day to puncture my bike tire. That’s when I spotted all the hardware strewn along the roadside—so many galvanized ingots to amuse future archaeologists. When I asked a TxDOT man in Rocksprings if I could keep them, he said, “Be my guest.”

There’s always more to catch the eye. Why would somebody toss a full tube of toothpaste out the window? Why, on such a remote stretch, would there be three tubes of toothpaste on the side of the road? I once had to swerve to keep from hitting a turkey gobbler who wouldn’t budge. Aoudad sheep and axis deer, oceans away from their homelands, are par for the course around here. One brisk morning, three whitetail deer galloped for miles in front of my bike, unable to escape the gauntlet created by the game-proof fences that hem both sides of the right-of-way. This was stampede enough, but when I looked up again, a quarter mile ahead, a bull elk stood on the centerline, its rack glowing like a chandelier in the early sunlight. And lots of roadkill, of course: rabbits—jack and cottontail—deer, snakes, feral hogs and one black cow.

At last at Kickapoo, the cavern boasts a spectacular eight-story, drip-formed, sequoia-esque trunk of limestone—speleothem—the largest in this state and, I’m confident, a bunch of other states as well. Tours of this colossus and other underground wonders are offered one day a week; Christmas, we well knew, would not be one of them. Meanwhile, the rest of the park is like the rest of this land—ruggedly handsome and unto itself. We rode for miles over roads and trails and never encountered another living soul. No country for magi, either.

The Christmas spirit came upon us, nonetheless. Between the park and home I saw a bright shape lying in the wayside stubble. Perhaps on any other day I would have thought nothing of it. But there it was: an infant’s woolen sweater, pink, with a smiling snowman wearing a scarf and skis. I find I am reluctant to throw this soiled relic away. It belongs, or belonged, to someone who passed my way in a hopeful season—and kept going. And it suggests that I have not so much adopted a highway, as I’ve become its foster child.

————————

Author John Taliaferro’s most recent book is All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay from Lincoln to Roosevelt.