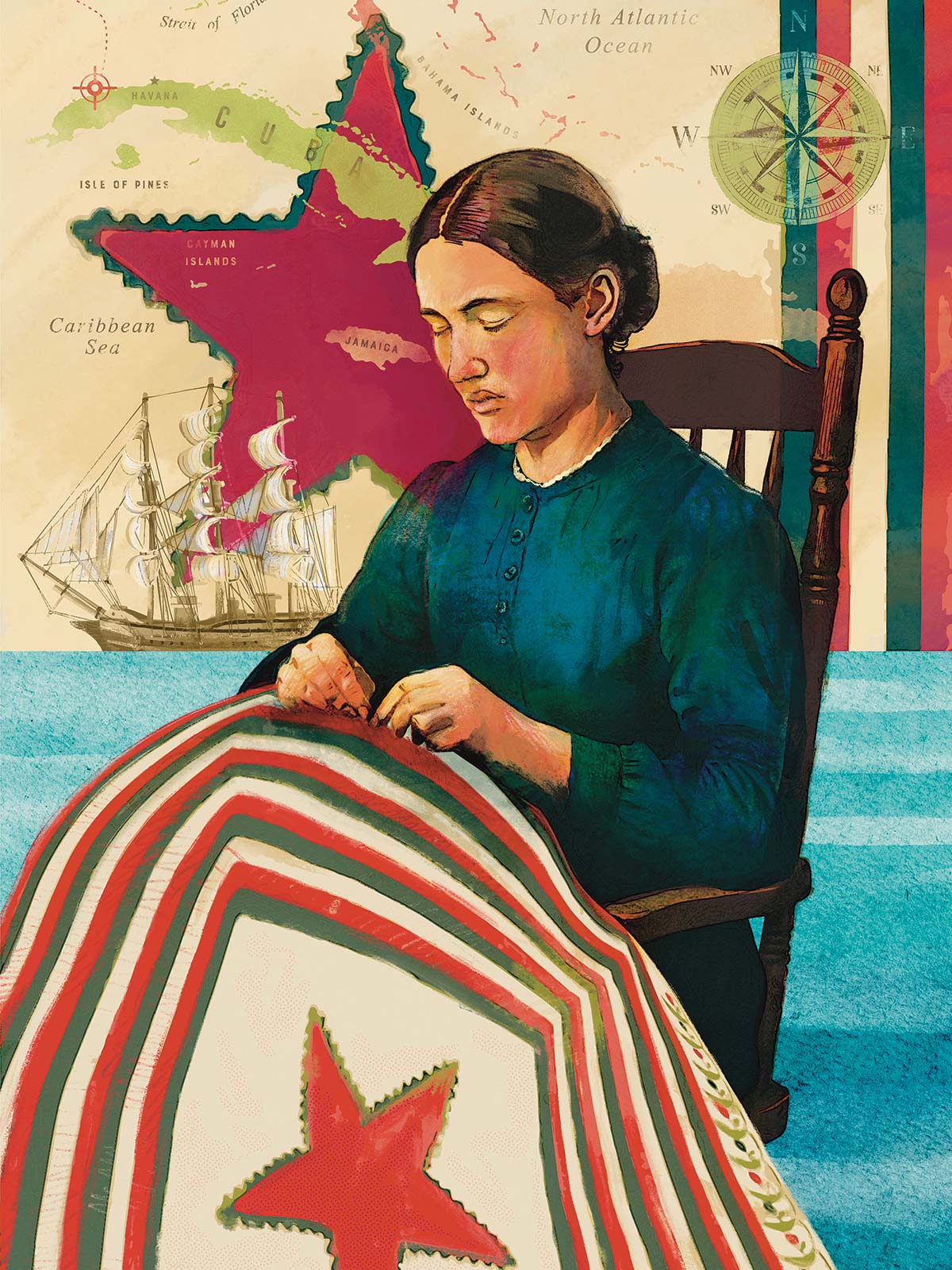

Wind gusts rocked ships anchored in Galveston’s harbor January 26, 1867, as the Linn family from Navarro County boarded a dilapidated brig bound for Brazil. Though the Derby was overloaded with more than 150 passengers carrying rationed goods like water, farm tools and seed, the Linns brought a Lone Star quilt that reminded them of home.

Nearly 160 years later, the quilt’s journey represents one of the most significant yet little-remembered mass exiles in U.S. history—one that scattered families, heirlooms and exotic tales of lost treasure between two continents.

After the Civil War, many Confederate families contemplated exile. Southerners fled to Mexico, British Honduras, Canada and Europe. But the most popular destination was Brazil, where Emperor Dom Pedro II expatriated thousands (estimates vary widely) of Americans who settled on cheap land to grow crops like cotton, coffee and sugarcane.

Exiles (nicknamed Confederados) were promised political freedom and, unfortunately, the ability to own slaves—before the practice was abolished in 1888.

One colony was led by Frank McMullan, a former Confederate officer from Hill County who planned to settle on a 500-square-mile property (about half the size of Rhode Island).

Getting out of America wasn’t easy. During Reconstruction, the country needed every hand to rebuild the devastated South, and the Rio Grande was patrolled by Union soldiers to stave off American militiamen heading into Mexico. With seaports bottled up, McMullan’s colonists shivered in tents on the beach in Galveston for weeks, waiting on a ship to Brazil.

Skilled émigrés lined the Derby’s manifest, including planters, engineers, judges, ministers, teachers, a physician and a dentist. Farmer George Alwin Linn; his wife, Amanda Pairalee Hammonds Linn; and their boys, William Hamlin, 6, and baby George, were also among those headed for Texas’ largest organized colony.

Amanda Linn carried with her a hand-appliquéd quilt she made in 1858. The roughly 90-inch-square spread is bordered with Turkey-red and Prussian-blue berries with upturned vines that reminded Linn of Texas. Linn, who was born three years after the Republic of Texas gained its independence from Mexico, centered the quilt with a five-pointed red Texas star medallion scalloped with blue edging.

Linn’s great-great-granddaughter Kerry Graham Rustin, who lives in Dallas, says she knows little about the quilt but remembers family lore about Linn as a strong pioneer woman who endured the incredible trials of exile.

For starters, a storm derailed McMullan’s expedition when the Derby crashed on rocks off the coast of Havana. Though everyone survived the wreck, valuables were swept out to sea. The quilt was salvaged after being submerged in salt water for several days.

Weeks later a rescue ship transported McMullan’s refugees to New York, where they lived in a drafty, run-down hotel awaiting transport to Brazil on an ocean liner named North America. In May 1867, the colonists pulled into Rio de Janeiro’s port.

It didn’t get easier from there. In his account of this short-lived diaspora, The Elusive Eden: Frank McMullan’s Confederate Colony in Brazil, the late writer and historian William Clark Griggs writes of colonists battling tuberculosis, floods, snakes, homesickness and isolation.

Within a year, most of the émigrés returned to the U.S. The Linns boarded a steamer to New Orleans on November 7, 1867, carrying the Lone Star quilt back to Navarro County, where they settled on a farm and had seven more children. Before Linn died in 1909, she willed the quilt to daughter Daisy Linn Chase of Los Angeles.

In 1947, Chase, then in her 70s, donated the quilt to Texas Gov. Coke Stevenson, who sent it to the University of Texas. Today the quilt is housed with 900 others at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History with a personal note explaining its shipwrecked, globe-trotting history.

“The Lone Star represents one young woman’s love letter to the state of Texas,” says Jill Morena, a registrar at the Briscoe Center. “[It’s] a visually striking, hand-sewn and early treadle machine-repaired quilt, its story made extraordinary by its dramatic loss and rescue and embodiment of the chaotic traversal from post-Civil War Texas to Brazil and back again.”