During the Great Depression, Trinity County native Claude Welch Sr. scrambled to find work—fishing, hunting, trading, picking cotton—anything the scrapping teenager could do to survive. He was not alone. Young men all over East Texas struggled to make a few dollars wherever they could to feed themselves and their families.

The stock market had crashed in 1929. Banks and businesses had failed, setting off a decade-long economic catastrophe. In the plains of West Texas, drought hammered an extra blow, creating the Dust Bowl conditions memorialized by John Steinbeck’s 1939 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Grapes of Wrath. In the Piney Woods of East Texas, years of forest clear-cutting without replanting left hillsides bare and depleted. Many timber companies shut down or moved on.

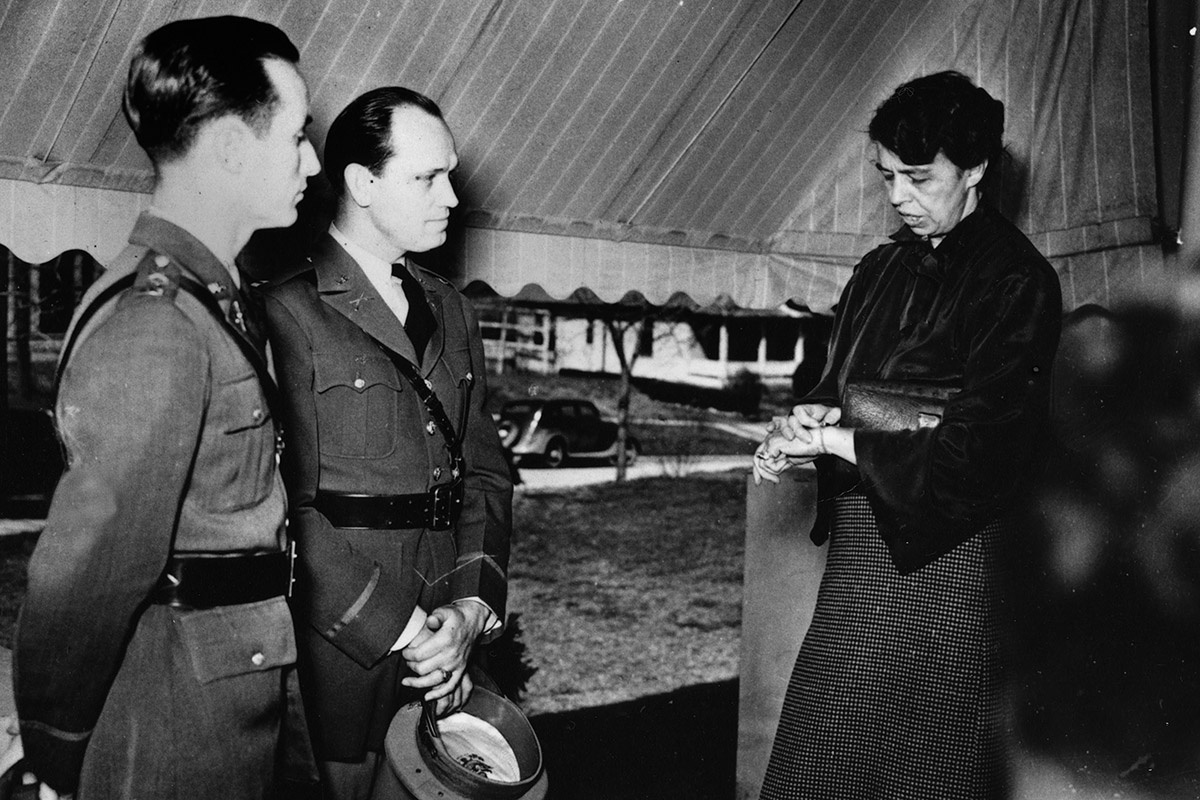

K.K. Black and Captain Van B. Houston of CCC Company 1823 and first lady Eleanor Roosevelt on the front porch of Sam McKinney’s Huntsville home March 7, 1937. During her visit, Roosevelt toured the CCC camp of Company 889 in New Waverly, the Sam Houston Memorial and its newly opened museum, and delivered an address to a crowd of 2,000 people packed into the Sam Houston State Teachers College gymnasium.

Courtesy Texas Parks & Wildlife Department

Dire conditions across the country contributed to the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as president in 1932. Right away, he enacted the New Deal, a series of federal programs and reforms to give people work and hope. One of his most popular relief efforts was directed at young men, especially those in rural areas.

Known as the Civilian Conservation Corps, the program began in 1933 and, over the course of nine years, enrolled 2.5 million jobless Americans, including some 50,000 Texans. By 1942, its job was done; after the U.S. entered World War II, a wartime economy began to expand.

In the middle of the Depression, a jobless Welch happened upon a CCC registration table in downtown Lufkin and signed up on the spot.

“I didn’t have any idea where I was going,” he recalled in a 1983 interview at the History Center in Diboll on the 50th anniversary of the CCC. But he knew it had to be better than his other options.

The CCC accepted Welch and put him on a train in Crockett, headed for Arizona. There he worked, building roads and stock tanks. Twenty years later, when Welch bought his first car, he took the family on the only vacation his son Claude E. Welch, an attorney in Lufkin, can remember: “Our trip was back to Arizona to the see places where he had worked.”

Indeed, for the rest of their lives, tens of thousands of Texans looked back on their CCC days as life-changing. Most worked to improve the state’s natural resources—from replanting destroyed forests and building rural roads to constructing parks and implementing soil conservation projects.

The CCC salary of $30 a month—$5 for each worker and $25 for his family—put quick cash into desperate communities. The CCC also bought food and supplies from nearby farmers and stores, further boosting local economies. The facts proved hard to ignore, even in East Texas where ideals of self-reliance reigned supreme.

A panoramic photograph of Company 888, Mission Tejas State Park, October 1934, taken just after the company received an award for Best Company of the Third Period (April–September 1934). Posed amid a backdrop of mess hall, garage and maintenance yard, the young men are aligned beside and behind the camp officers and administrators. Segregated to the right are the company’s nine African American members.

Courtesy Texas Parks & Wildlife Department

“You have a devastated landscape and a federal program willing to help,” explains historian Jim Steely, an East Texas native who wrote Parks for Texas: Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal. “Even in the most conservative areas, there was not a lot of political resistance to federal help. The New Deal was so successful because Southern politicians knew they needed help the most.”

A Better Life in Camp

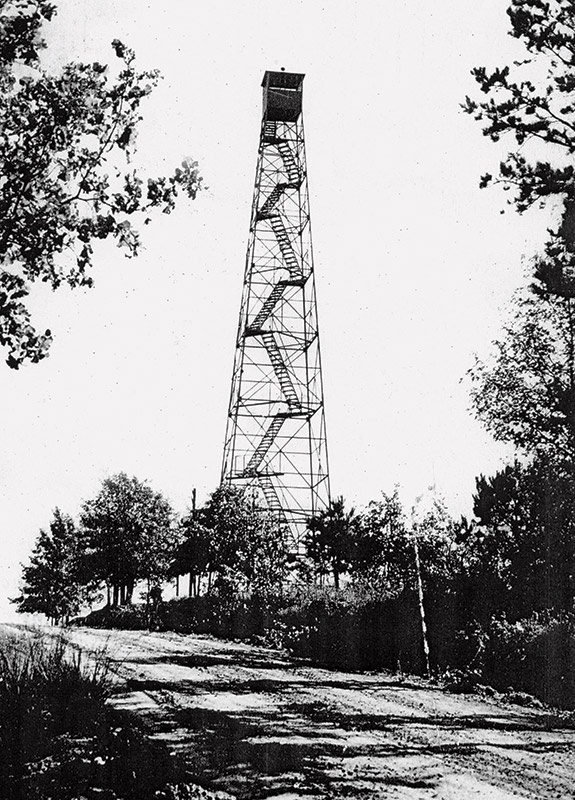

Reforestation was an early goal of the CCC, but there were no federal lands in Texas. The government bought hundreds of thousands of depleted acres in what are now the four national forests of East Texas—Davy Crockett, Sabine, Angelina and Sam Houston. The U.S. Forest Service and Texas Forest Service cooperated in a monumental effort to create a second-growth forest and implement soil and water conservation practices. The project brought immediate economic support while promising renewed forests, outdoor recreation and wildlife habitat for the future.

A 1934 CCC photo shows the original camp structures of Company 888 in Weches, formed in 1933 as an integrated work camp.

Courtesy Texas Parks & Wildlife Department

Young workers from poor families signed up for military-style companies of 200 men each. Ages ranged from 17 to 25 (later 16–28 or even older for World War I veterans). The CCC also hired “locally experienced men” to supervise and train enrollees and to provide skilled labor as craftsmen, teachers, architects and engineers.

The CCC district office in Lufkin organized area companies into camps across southeast Texas—at Ratcliff, Nancy, Jasper, Beaumont, Woodville, Livingston, Huntsville, Kennard, Groveton, Madisonville, Trinity, Apple Springs, Lufkin, Nacogdoches, San Augustine, Coldspring, Honey Island, Oakhurst and Maydelle. Enrollees typically served two six-month terms, then returned home, making way for new workers. During their time in camp, workers got three meals a day and tent or barracks housing near their work sites—plus clothes, boots and medical care. Life was clearly better than before—so much better, in fact, that the average Lufkin district enrollee gained four pounds in their first weeks of eating camp food. One happy worker remarked that the toothbrush found in his “three-C’s” toiletries kit was the first one he’d ever owned.

U.S. Army officers supervised the six-days-a-week work routine. Bugle reveille, saluting and flag ceremonies started and ended each long workday.

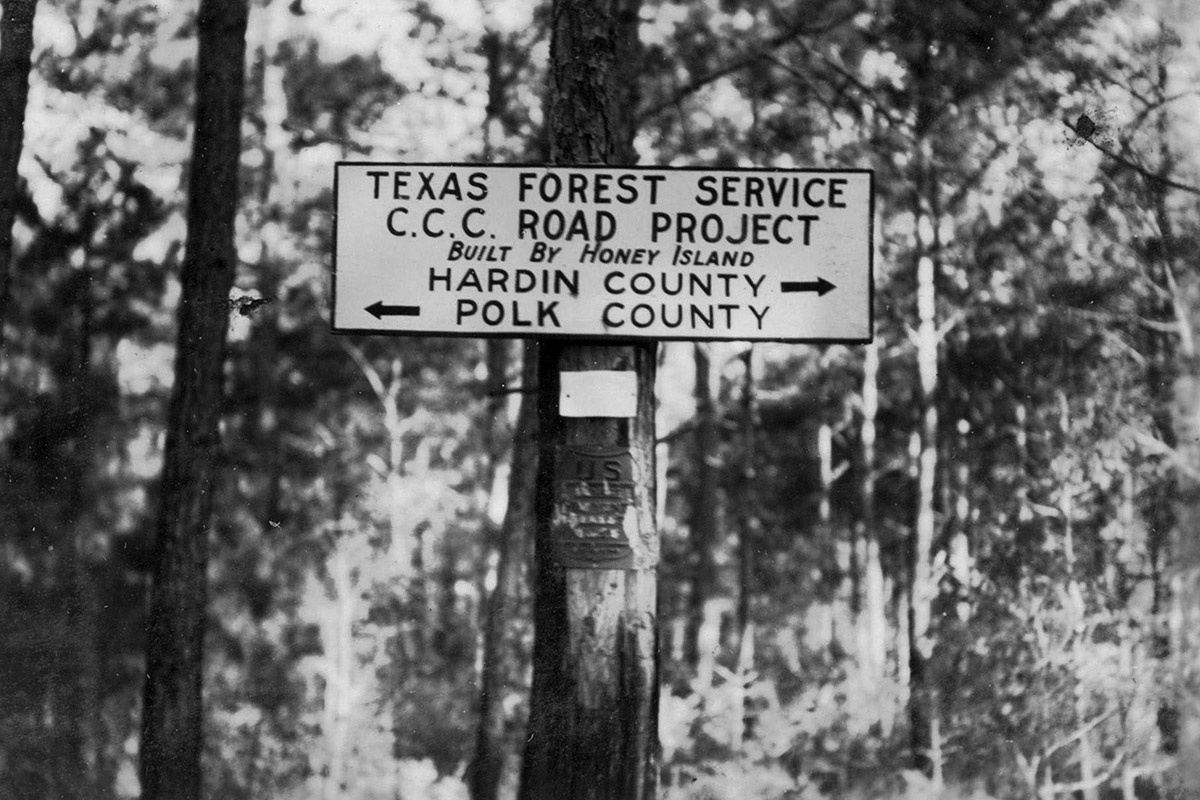

The most important project for this camp was the clearing of old tram roads to provide firebreaks and routes for Forest Service workers to fight fires. These roads had been used by lumber companies to carry cut timber for the mills. It had been at least 30 years since the tracks had been removed and the underbrush and trees of the Big Thicket had grown. This camp was located on private land near the Honey Island swimming pool, a popular attraction fed by artesian mineral water.

Lamar University Special Collections

“I learned about discipline,” said Jesse W. Lazenby in a 2018 article in the Tyler County Booster. “I was a kid when I went in but a man with more respect for others when I was honorably discharged,” noted Lazenby, who died last year at age 97, the last survivor of Woodville’s CCC Company 891.

Country lads who worked in “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” as it was called, knew the challenges and rewards of hard outdoor labor. In a 1985 interview at the History Center in Diboll, Angelina County native Marvin Baker recalled how his company restored pine forests from Zavalla to Beaumont.

“We would line up like a marching army and set these little pine seedlings out by hand … over them hills and down in the valleys setting those pines out,” he said. “Now, some of them are 50 years old. I see them and I think about having a part in [what] is a beautiful tree today.”

Camp life wasn’t always arduous. After a day’s work was done, enrollees had free time to learn a trade or take a class to further their education. Some camps even published their own newspapers. Many hosted baseball, basketball or football teams. More than one romance was sparked when enrollees rubbed elbows with local women brought to camp for dances.

Huntsville State Park.

John B. Chandler

Most camps worked in reforestation and soil-conservation projects. Others took undeveloped land donated near towns and transformed them into recreational areas. The State Parks Board assigned a manager to oversee road, lake and building projects using architectural guidelines of the National Park Service. The NPS rustic style, as it was known, took materials like stone and timber, found locally, and fashioned them using simple tools into low-lying structures that blended into the natural surroundings. CCC companies ultimately built more than 50 recreational parks, most of which remain in use, including 29 state parks operated by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

A Legacy of Parks and Recreation

In the 1930s, Walker County voters authorized the purchase of former timberland for what is now Huntsville State Park. Early on, two integrated (but mostly white) forestry companies worked on reforestation, firefighting and flood control projects. They also built forest roads visible now only along the park’s Triple C hiking trail.

Huntsville State Park’s main hall in November 2014.

John B. Chandler

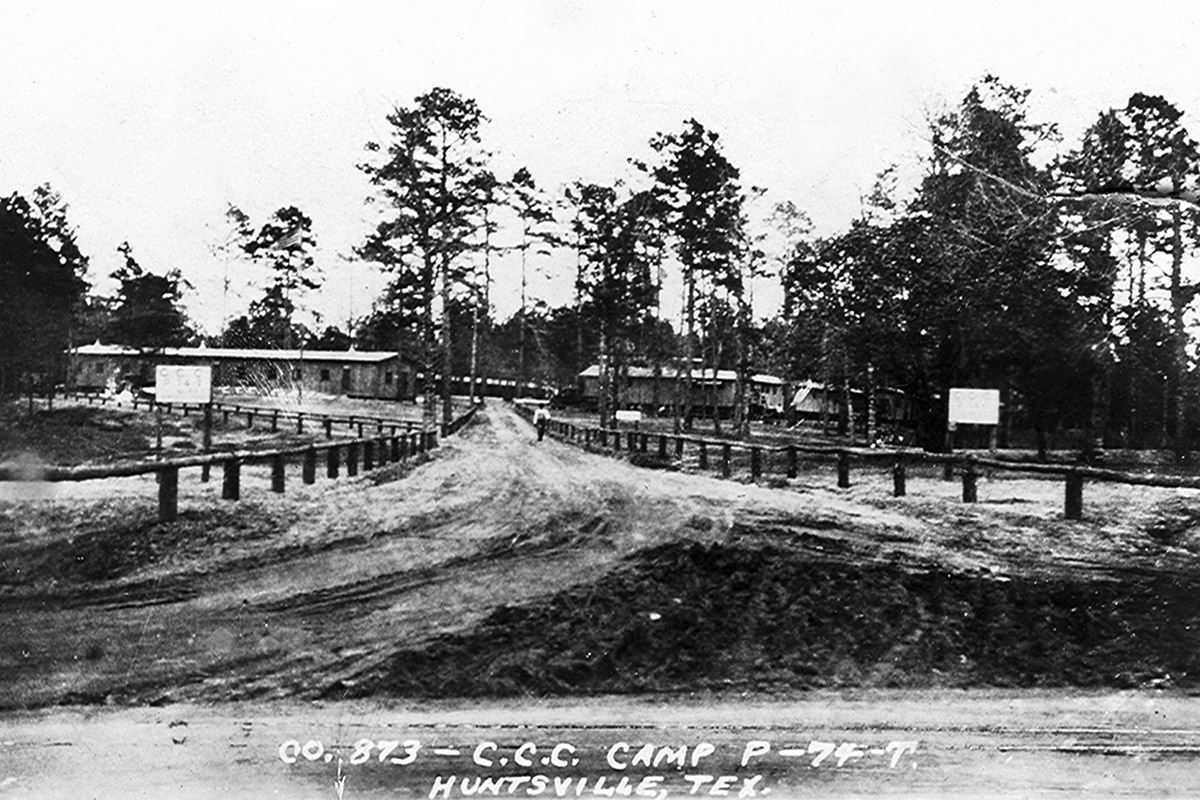

By 1935, CCC companies in Texas and across the South were segregated. In 1937, CCC Company 1823—composed of African American veterans of World War I and their Anglo American supervisors—constructed an earthen dam, lakefront lodge and boathouse for the park. In the fall of 1940, a deluge dumped 12 inches of rain within 48 hours, and the dam collapsed. Two years later, the CCC workers shipped off for war duty and the camp closed.

Workers from another New Deal agency, the Works Progress Administration, joined state prison laborers to rebuild the dam, and Huntsville State Park opened in 1956. Its camping, hiking, nature study and water sports make it one of most popular state parks.

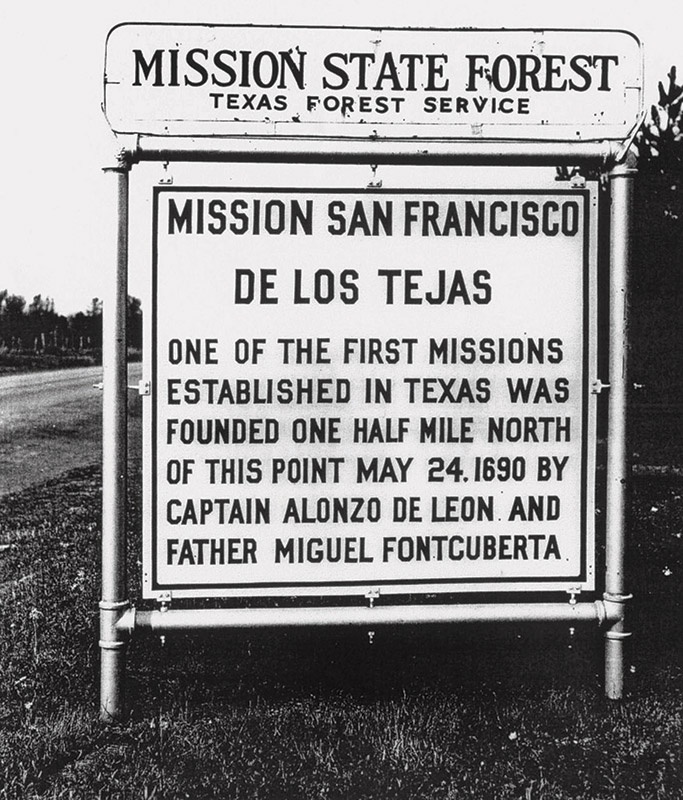

CCC work in Houston County got a boost during the lead-up to the 1936 celebration of the Texas centennial. State officials wanted to encourage tourism, so they engaged CCC forestry Company 888 at Weches to develop a park nearby, where historians recently identified the site of the 17th-century Spanish mission San Francisco de los Tejas.

Enrollees cut pine logs to use in building a commemorative mission church in typical NPS rustic style. They also constructed a pond and several hiking trails in what is now Mission Tejas State Park. In the 1970s, the park further enhanced its historic character by adding the restored Joseph Redmond Rice family log home, which honors the Anglo pioneer era of the 1820s.

As CCC rebuilt the forests of East Texas, it also established within those forests a number of popular recreational areas—including Ratcliff Lake, Red Hills Lake, Boykin Springs and Double Lake—that continue to attract nature lovers across the region.

The legacy of Roosevelt’s Tree Army remains not only in the region’s parks, forests and recreational areas. It survives in the lives of families who found a way out of the Great Depression, says Steely.

“At the time of the Great Depression, most people only knew the places where they lived,” he says. “They didn’t really know any other way of life. The Civilian Conservation Corps gave them the skills and experiences that changed their futures and that of the nation. It’s no small statement to say that the CCC saved a generation.”