I like to think I’m a good Texan, born and raised. I’ve visited most every shrine in our great state. I’ve hiked our highest mountain, photographed the official bison and longhorn herds, and traveled the length of the Goodnight-Loving Trail. I’ve spent countless hours at our hallowed battlegrounds: Goliad, Gonzales, San Jacinto and the Alamo. But until last year, I had never been to the birthplace of our revered republic.

Washington-on-the-Brazos is a state park honoring the site of the signing of the Texas Declaration of Independence on March 2, 1836. Every March, the park celebrates Texas Independence Day with living-history re-enactments, educational programs, crafts, food and live music. This year, the celebration is March 5–6, commemorating the 180th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence from Mexico and the 100th anniversary of the state park.

On a brisk but cloudy Texas Independence Day, I’m driving through the rolling prairies 20 miles northeast of Brenham. I turn onto a curving drive that delivers me to the birthplace of Texas: a 293-acre park on the original site of the town of Washington. I’m here to learn a few things that were left out of my seventh-grade text on Texas history.

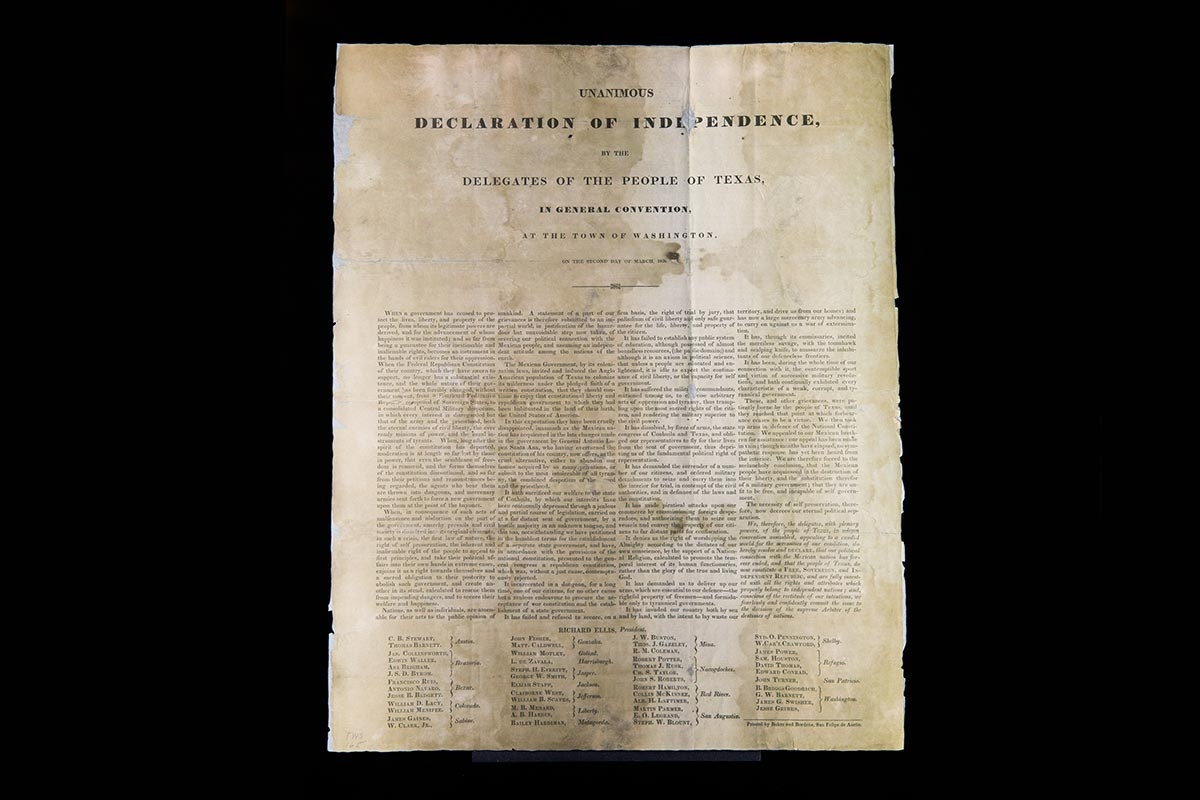

Despite the gloomy weather, visitors have filled the parking lots then taken over the park paths and picnic tables. In the visitors center, families inspect a replica of the Texas Declaration of Independence along with some of the artifacts unearthed on the park’s grounds. The name of the site, Washington-on-the-Brazos, distinguishes it not only from the nearby town of Washington but also from that other capital city, Washington on the Potomac.

“The events that happened here in Washington not only helped shape the Republic of Texas but also the young state of Texas,” explains Adam Arnold, a park ranger and history interpreter.

Arnold, a seventh-generation Texan, was living in Oklahoma during the time most schoolchildren learn about the Texas revolutionary period. “I missed out on most of the school studies, so I had a lot of catching up to do when I got to the park. It’s more than just the Alamo and San Jacinto. There are so many amazing stories about the people that were here.”

Indeed, “amazing” is an apt description of those events and people who participated. In 1836, as Travis, Crockett and Bowie were spilling blood for the Texian cause at the Alamo in San Antonio, 170 miles to the northeast, another group was spilling ink to forge a new republic. The 59 signatories of the Texas Declaration of Independence gathered in this town along the banks of the Brazos River near La Bahia highway, upstream from Houston. Their convention hammered out the language that defined the republic even as Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna hammered the walls of the Alamo.

They met in an unlikely Independence Hall. Today’s replica of the building occupies the exact spot where those Texians signed their names to the declaration on March 2, 1836. Today, I walk a tree-lined path from the visitors center to Independence Hall so I can see our Philadelphia, in frontier Texas style.

Back then, the Washington townspeople offered the meeting space to the delegates free of charge in the hope of stimulating the local economy. The town had been officially founded the prior year, and the only place large enough to house the gathering was an unfinished building owned by a local gunsmith. It lacked windows, doors and part of its roof.

A cold front swept into the area and sent temperatures plummeting to near freezing the week of the convention. Most delegates couldn’t find lodging in the only inn, and food was running low by the end of the 17th day. That was when everyone evacuated ahead of the Mexican troops marching east, energized by their victory at the Alamo. Some delegates fled with settlers, staying ahead of the Mexican army that was known to take no prisoners. Their flight was dubbed the Runaway Scrape. Other delegates rallied to the fight, following newly minted Commander in Chief Sam Houston to the decisive Battle of San Jacinto.

To my surprise, more than half of the signatories were recent arrivals to Texas from the United States. They were illegal immigrants in violation of the immigration ban imposed by Mexico in April 1830. They hailed from 11 states and five foreign countries. Only two of the signatories were native Texans: José Antonio Baldomero Navarro and José Francisco Ruiz.

The contemporary Independence Hall appears to be identical to the original, according to accounts from the 1830s. No drawings or plans for the building are known, but the structure sits on the same foundation stones left from the 1830s. Inside the shadowy room, simple desks and chairs are arranged for a meeting, and white curtains hang in windows that hold no glass. Independence Hall sat near a bustling ferry town of 100 people on the edge of the frontier, and looking through the simple wood frames, I wonder if the landscape now appears as undeveloped as it must have been then.

A 1912 fire burned the last of the original buildings, and the remains of the town have been lost under layers of soil. “The gopher holes are how we find lots of things,” says Barb King, park ranger at Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site. “It would cost millions of dollars to dig, but kids and visitors find things the gophers have dug up.” These gifts from the gophers include pottery shards, fragments of porcelain, tools and the occasional dollar coin from 1837. “We always encourage visitors to not pick anything up but tell us when and where they see something,” King says. Artifacts lose much of their context and potential for historical accuracy if they are moved from the site of their excavation. There’s hope for an archaeological field school to establish professional digs at the park, but until then, the historical treasures remain buried.

The park paths are laid out as the streets once were, and a glance at the historic city maps orients me to what once was. I stare into the overgrowth summoning ghosts of the revolution: here an inn, there a brickyard, then a stable.

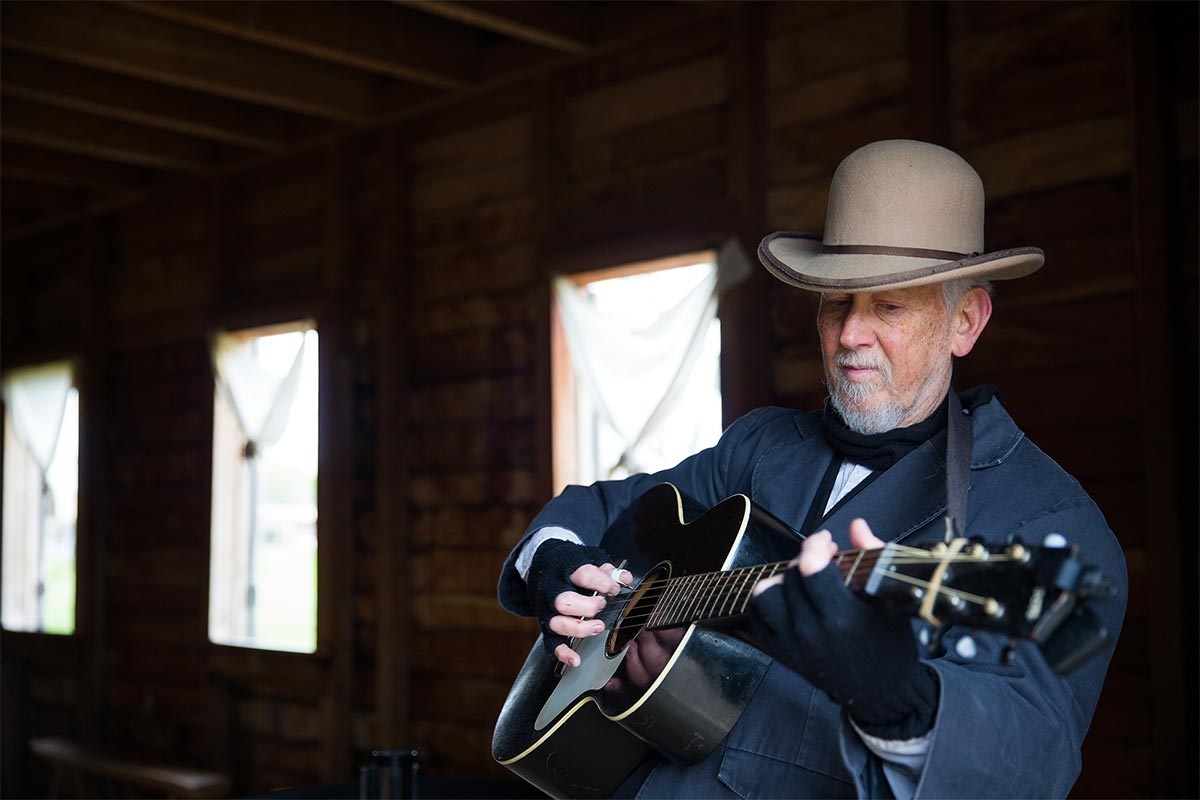

The crowd today is a diverse group of families, foreigners, history re-enactors and locals. The celebration continues as the Sweet Song String Band’s guitar and fiddle players strike up a song and, in period costumes, lead the crowd to the monument erected by Brenham schoolchildren in 1899. Today’s schoolchildren lay a wreath in honor of the occasion.

Down the hill, a demonstration of cannons and guns draws onlookers every few hours. Visitors crowd the perimeter, straining against the safety line to get closer to the explosions of noise and gunpowder. Each kaboom generates cheers.

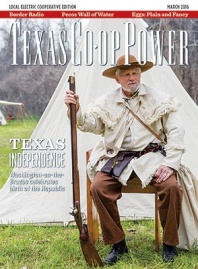

Living-history re-enactors have set up camp nearby. I find Jim Richardson, a recent convert to living history, cleaning his period rifle outside a tent. Richardson, from McKinney, has traced his family history back to the de Zavala Colony in 1835.

For Richardson, Washington-on-the-Brazos and other historic sites of the Texas Revolution provide an opportunity to connect emotionally to the people of that era. “What could those people have been thinking? What did it feel like to be so close to the most formidable army on Earth?”

Richardson also says he believes that understanding the more nuanced political history helps us preserve our democratic principles. “I think it’s important to visit these sites for a historical perspective. To preserve our freedom, it’s important to know what happened in history.”

I experience a mix of somber reflection and sheer enjoyment at the park this Independence Day. At the Star of the Republic Museum, Jack Edmondson is performing the life story of Sam Houston for a packed theater. He elicits laughter and applause in equal measure.

Washington thrived during a brief window as a pivotal ferry town along La Bahia highway. It was the Texas capital, briefly, in 1842, and the last president of Texas, Anson Jones, lived in nearby Barrington even as the people of Texas decided to let their nation become the 28th state of the United States in 1845.

With statehood, the story of Washington, Texas, faded. This tiny hamlet that birthed a nation returned to the land again.

——————–

Julia Robinson is an Austin photojournalist.