Of all the musical instruments brought to Texas by German, Czech, Polish and Moravian immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the accordion made the most unexpected inroads among Mexican, Cajun and Creole communities who embraced it as their instrument of choice. Generations later, squeezeboxes still move Texans.

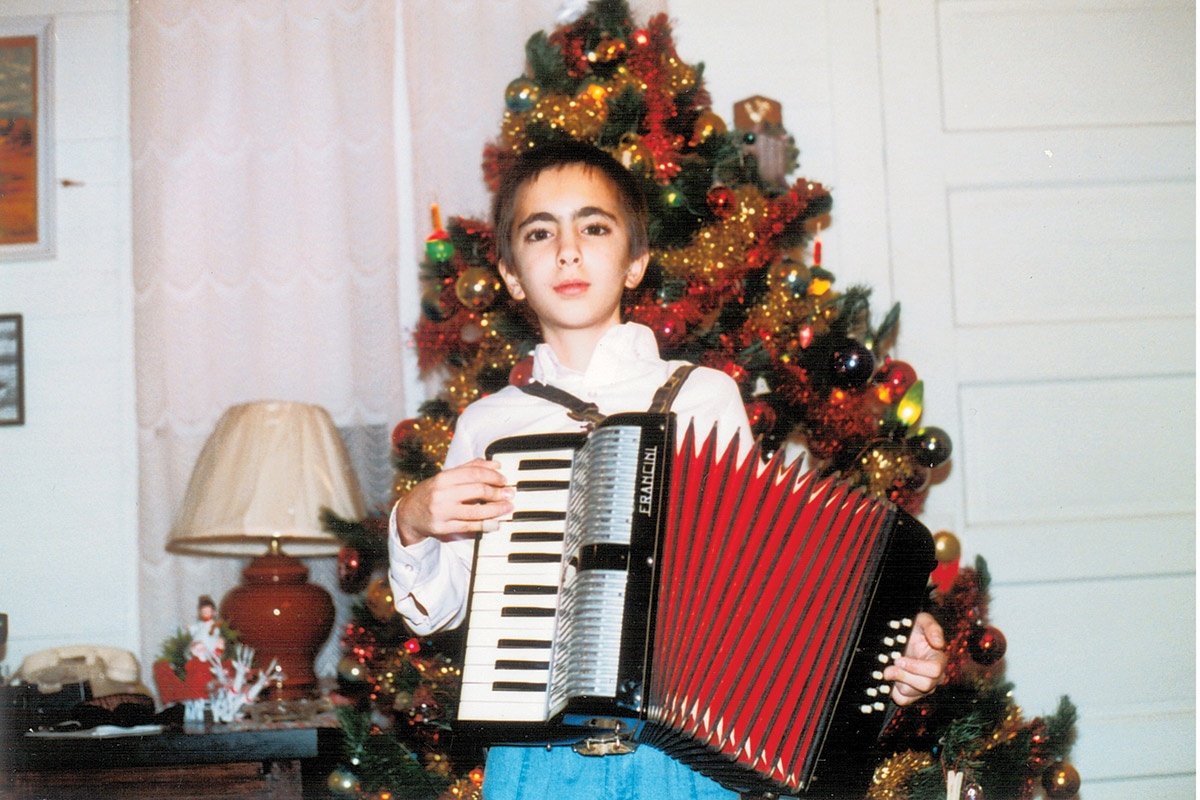

Chris Rybak, known as the Accordion Cowboy, who hails from Hallettsville, explains that when he picked up the instrument 30 years ago, at age 11, accordion-playing bandleader Lawrence Welk was a big thing. “But that also made accordion not so cool,” he says, adding that now it’s heard in jazz, rock and a wide variety of other musical genres. “It doesn’t have to be just your grandpa’s oompah anymore.”

Rybak as an 11-year-old.

Courtesy Chris Rybak

Packing the full-bodied sound of an entire band into one instrument, the accordion, invented in Europe in the 1820s, provided entertainment at dances of all kinds as Texas was settled. Without the need for electricity or amplification, its sound carried farther than stringed instruments.

The accordion was a key instrument for western swing bands in the 1930s and ’40s. It remains the most versatile musical instrument going in Texas, straddling regions and borders and injecting its sound into rock, country, blues, jazz and zydeco. It’s the defining instrument of conjunto, the folk music of South Texas, and the faster-paced norteño, a folk music of northern Mexico that is similar to conjunto.

Without the accordion, there would be no Mark Halata at Wurstfest, no Brave Combo playing WestFest, no Ennis Czech Boys working the National Polka Festival, no Fritz Hodde and the Fabulous Six performing at an SPJST hall.

The European-style accordion, the traditional large instrument with piano keys on the right-hand side that functions like a glorified organ, is favored by the Bohemians, Czechs, Poles and Germans of South and Central Texas; some Zydeco bands around Houston and southeast Texas; and Fort Worth’s Ginny Mac and Austin’s Debra Peters. It can weigh upward of 30 pounds.

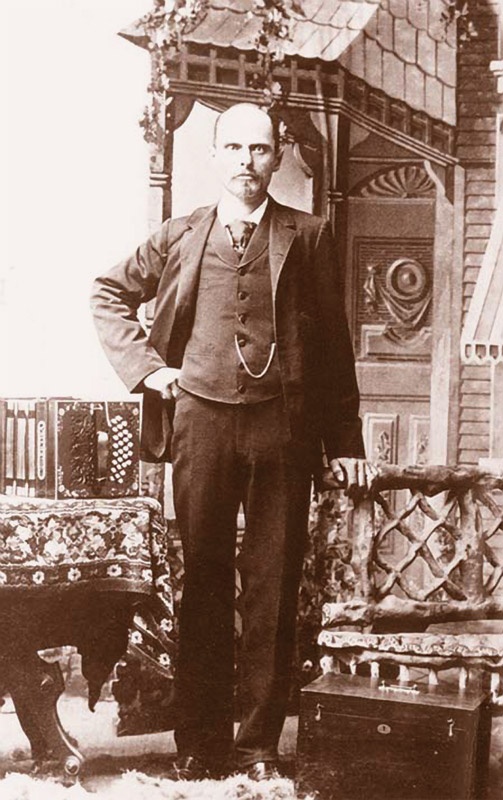

Accordionist and bandleader Emil Schuhmann of Fayette County in the 1890s.

Winedale Photograph Collection | The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Conjuntos and some zydeco bands favor the smaller, diatonic model of accordion with buttons on both sides that change notes as you push and pull and has considerably faster action. Texas Cajuns play an even smaller, simpler diatonic model with fewer buttons.

Rybak explains that Czech, German, German-Polish, Tejano and Cajun music each embody a distinct style. “On the other hand, when you go to a conjunto place,” he says, “the band will throw in a few Czech songs. And vice versa. The accordion is distinctive, and it can cross boundaries and cultures.”

The universality of the accordion is celebrated at the Accordion Kings and Queens at the Miller Outdoor Theatre in Houston on the first Saturday in June, a production of Texas Folklife. All the bands onstage feature accordions as the lead instrument, but the performers sing in English, Spanish, French, German, Polish and Czech, reflecting each group’s ethnic background. Despite those differences, everyone dances the same on the dance floor, moving in a counterclockwise direction.

These days, Rybak says he mostly uses a digital accordion, which has changed his instrument much the way a digital keyboard changed piano playing. He can create blaring trumpets to open the Johnny Cash standard Ring of Fire.

“I would say for most shows, I play 70 or 80% with a digital accordion,” he says. “And that’s what the new generation really loves, too. They can do anything on it.”

Although Joe Nick Patoski gave up piano accordion for violin at age 7, he owns a button accordion autographed by Flaco Jiménez.