The made in Texas moniker gets applied to so much more than boots, hats and Texas-shaped tchotchkes.

I went in search of distinctive makers and found diverse artisans with deep thoughts about the act of creation. Whether fulfilling grand ambitions and pushing the limits of a craft or rendering spiritual communion and psychological healing, these Texans use their minds and hands to transform raw materials into objects of beauty and purpose.

This holiday season, let’s remember to invest in our local makers. Here are a few from Co-op Country to get you started.

Odin Clack in his workshop, Odin Leather Goods

Julia Robinson

The Character of Leather

Odin Clack wandered into a leather store one day in 2012 and exited with $200 worth of goods and a new curiosity. He wondered if he could make a laptop sleeve from the leather and began tinkering at his dining room table. The graphic designer found a new challenge in leathercraft and was soon making wallets, belts and bags for family and friends.

“The thing I love about leather is that the way it looks to me is different from the way it will look in a year from now. How we use it affects the way it looks and feels,” Clack says. “Every dent and scratch tells a story.”

In 2018, Odin Leather Goods moved out of the family’s garage and into a workshop in Coppell, near the Tri-County Electric Cooperative service area. Odin and his wife, Rachelle, work with one shop assistant to fulfill orders for their wide range of products. “When people buy local, they know their dollars are going towards daycare and swimming lessons and supporting a local family,” Clack says. “It also trickles down because I buy my materials and hardware from other U.S. companies.”

Volundr Forge

Julia Robinson

Forged With Heart

J. Alex Ruiz has always loved making things with his hands. He spent his childhood sculpting and crafting historical replicas, which led him to study archaeology in college, where he discovered the tools and crafts of long ago.

A penchant for colonial-era ironwork brought him into a blacksmith shop, where he made functional ironworking tools like bladesmithing tongs, hammers and knives.

As a maker, Ruiz feels a deep kinship to those historic people we learn about through artifacts. “When I go to museums and look at historical weapons or ironwork, I like to see the flaws,” he says. “As someone who actually makes these things, I can spot if something has been broken and fixed.”

Ruiz, a member of Karnes Electric Cooperative, began teaching and performing demonstrations around Texas and earned a spot on the History Channel’s Forged in Fire competition, where he won $10,000 for a medieval horseman’s battle axe. Volundr Forge is Ruiz’s business that he runs part time from his home in Adkins. It’s not uncommon for his shop to reach 120 degrees, and there is a 16-week backlog for his custom knives. “My market is the everyday guy that wants something handmade that’s going to last a lifetime,” he says.

Tara Hutchinson in her home studio in San Antonio

Julia Robinson

Jewelry and Time Heal All Things

In 2006, Tara Hutchinson was serving her 10th year as a soldier—a military police sergeant on deployment in Iraq—when a truck she was in was hit by an improvised explosive device. Hutchinson lost her right leg above the knee and suffered a traumatic brain injury that left her with muscle tremors and difficulty controlling fine motor skills.

“I couldn’t use my hands to do anything after my injury,” Hutchinson says. “I couldn’t write. I couldn’t feed myself. I had no control over my hands at all.”

The loss of a career she loved and her independence sent Hutchinson into a deep depression. “I definitely contemplated suicide on multiple occasions because I couldn’t see any kind of a worthwhile future for myself,” she says.

A physical therapist suggested she find a new hobby to help her regain muscle strength, and Hutchinson found jewelry making. “Before that, I didn’t even own any jewelry at all,” Hutchinson says. “I was in the Army and playing in the dirt with the guys.”

She took a class, and after making jewelry for six months, Hutchinson’s jerky hand movements were smoothed out. Making gave her new purpose and new hope. She spent two years researching jewelry making and became a master goldsmith.

Hutchinson runs Tara Hutch Jewelry out of her home studio in San Antonio. “Now to be able to help women feel beautiful is the most amazing thing ever,” she says. “People can take home something that reminds them that if I can make it through this hard time, anyone can.”

Maura Grace Ambrose

Julia Robinson

The Fiber of Our Being

Maura Grace Ambrose studied textile design and fiber arts at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia, where she found a passion for natural dyes and quilting. “The natural dyes were soft and chalky and harmonious, and it played into the poetic, beautiful parts of art,” says Ambrose, a Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative member. “The colors were alive because they came from something that was alive.”

Ambrose runs Folk Fibers from her home studio in Bastrop, where she forages and tends an organic garden for plant-based dyes. It takes about 250 hours to make a bed-sized quilt with Ambrose’s process of natural dying and hand stitching. “I can’t compromise on the process because that’s what makes them special and makes them an heirloom,” she says.

For Ambrose, making is a creative expression, the revival of an ancient process and a way to connect to a community. “The long-term goal is to teach, spread the word and inspire others,” she says. “In those exchanges and conversations, nothing else matters. The women become so empowered to make quilts themselves.”

Drapela Woodworks

Julia Robinson

Working With Wood

Ryan Drapela grew up selling watermelons near his home in El Campo, southwest of Houston. “I was born with the hustle,” Drapela says. He sold small skateboards in third grade, duct tape wallets in middle school, and candy and jerky in high school.

“We grew up super broke,” explains Drapela, a member of Wharton County Electric Cooperative. “I started buying all my school clothes and supplies myself in the seventh grade.” Drapela walked into his high school woodshop and found a new business opportunity creating cutting boards from wood scraps. His offerings expanded to clipboards, bottle-cap tabletops and custom plaques. The orders from his Etsy store kept growing.

In May 2019, Drapela earned his degree and the title of Entrepreneur of the Year from Texas A&M University’s agriculture school. He runs Drapela Woodworks with 15 employees fulfilling 1,000 orders a week for his Man Stands docking stations. “I grew and grew from persistence and hard work, not pure talent, not pure intellectual knowledge,” he says. “Just from working harder, longer and more consistently than competitors.” For Drapela, his success is a measure of his ability to create change in the world, whether it’s a new product or jobs for the local economy. “Whatever I’m doing, it’s a way to chase my capacity,” he says.

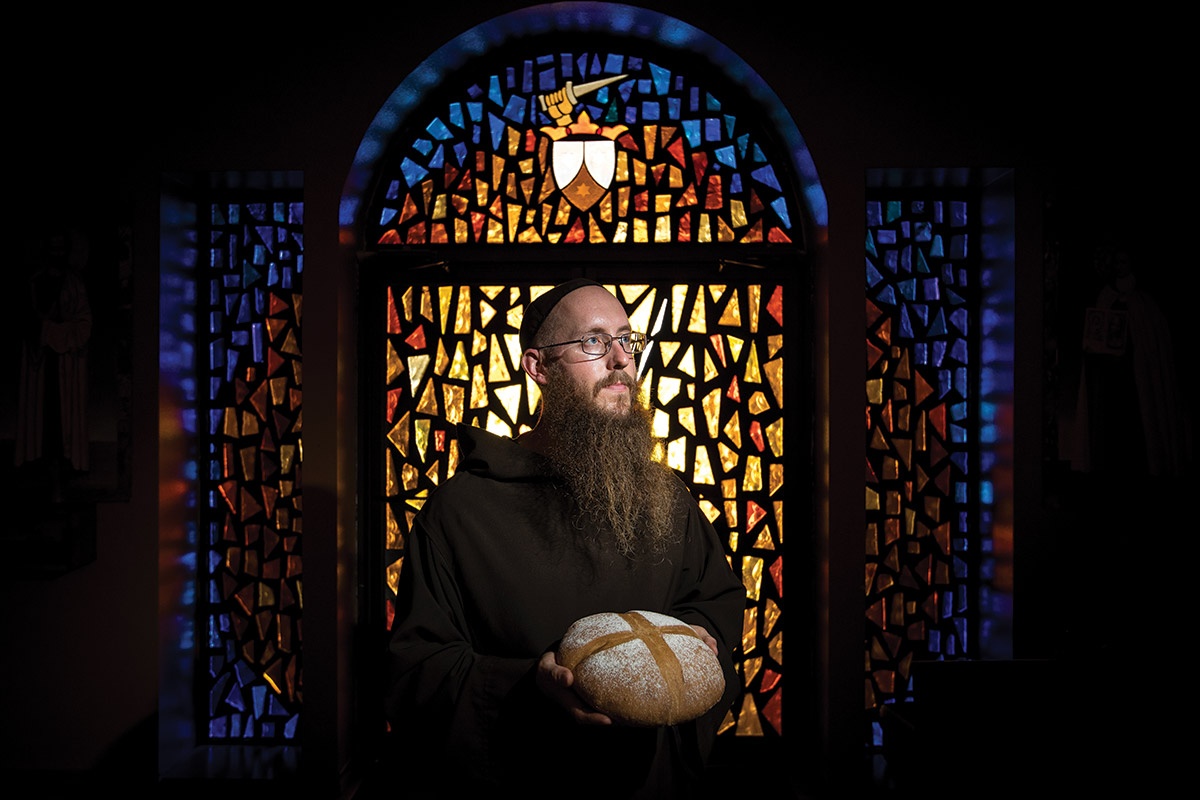

Brother Augustine

Julia Robinson

Divine Intervention

Tucked into the gentle hills of Christoval, 20 miles south of San Angelo, you’ll find the Mount Carmel Hermitage Monastery, where the Hermits of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel make breads, jellies, fudge and honey. In 1991, Father Fabian, a priest from San Angelo, founded the hermitage with $2,000. Until 1994, he lived alone in a remote house. “He had the vision, the grace and the leap of faith to give it all up and start from zero,” says Brother Martin, who joined the hermitage in 2001.

“Monks have always worked to support themselves by their own hands,” Martin says. “There is a beautiful relation between making food and the idea of communion. We are making something that people are going to put into their bodies for their sustenance and enjoyment, and there’s a communion of spirit there.”

Today, the eight monks of the Mt. Carmel Hermitage live in silence and solitude. “Our order is a very simple order,” Martin says. “We’re not interested in scholarly work or writing papers or books. We just try to pray and work and maybe we do badly sometimes, but we try. We try hard.”

The hermitage has a gift shop and an online store from which they ship all over the world.

See more of Julia Robinson’s work at juliarobinsonphoto.com.