It’s a breezy, overcast 80-degree day in Marfa as a dozen or so volunteers rotate jobs in a brick-making assembly line.

Billy Joe Moore, 12, has the hardest job. He hoists small buckets of clay, sand, straw and water into a gas-powered mixer, like those used for concrete. His mother, Erin Moore, says the homeschooling, beekeeping family from Fort Davis is here to learn about adobe-making by doing it, getting into it.

It’s also for a great cause: These bricks will be used in the restoration of a historic church in a remote outpost, turning a former Catholic house of worship into a community center.

“It’s so neat to hear about the history of the church and the culture of the region,” Erin says. “Who wouldn’t want to get involved in this?”

In the ghost town of Ruidosa, 90 minutes southwest of Marfa in far West Texas, the adobe El Corazón Sagrado de la Iglesia de Jesús (Sacred Heart of Jesus Church) is awaiting resurrection.

Completed in 1916, the church fell victim to blowing sand and rain that wore away the adobe before and after the droughts of the 1950s dried up the Rio Grande and the small agricultural community. By 1960, the church and town had been abandoned.

From left, Terry Bishop, Martin Rivas and Claudio Nuñez load new adobe bricks onto pallets during a Friends of the Ruidosa Church workday.

Erich Schlegel

A Friends of the Ruidosa Church work crew.

Erich Schlegel

Native salts eroded the foundation. Huisache branches battered the northeast tower. Attempts to restore the church, which claims the largest traditional adobe arches in Texas, faltered until the nonprofit Friends of the Ruidosa Church acquired the title to the Texas Historic Landmark from Presidio County after it was given the deed from the Diocese of El Paso in 2019.

With ownership, the Friends began work to preserve as much of the original adobe as possible, to restore structural strength and to repair the damage done over 110 years. That meant making sun-dried adobe blocks—thousands of them, one at a time, starting in 2021.

For more than 10,000 years, adobe has been used as a building material, favored because its high thermal mass absorbs heat during the day and releases it at night.

“In recent generations, adobe-making skills have been lost, since the knowledge is rarely written down,” says Joey Benton. His Marfa design and restoration company, Silla, has completed restorations of adobe buildings at Fort Davis National Historic Site and Big Bend National Park.

During the Friends’ May Adobe Day, kneeling men and women scoop Billy Joe’s fresh adobe mix from tilted wheelbarrows with their bare hands and tamp it into wood forms.

Bishop carries a fresh brick.

Erich Schlegel

Friends of the Ruidosa Church carry out their rebuilding mission along the Rio Grande.

Erich Schlegel

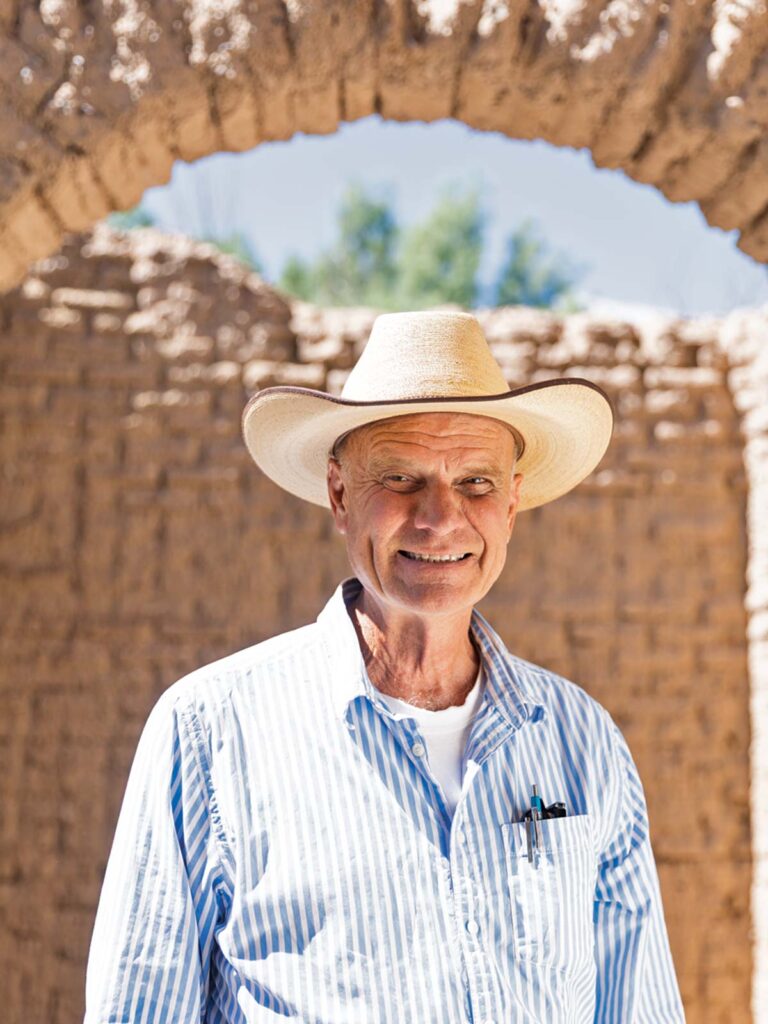

“The earthen-structure community has no secrets or hidden techniques,” says retired architect Mike Green, who is leading the restoration.

Erich Schlegel

Others lift the forms off the freshly minted 10-by-18-by-3.5-inch blocks. They rinse off the forms in a large water trough and place them on black tarps, ready for the next batch.

The adobe blocks dry for a month in the sun, turned periodically like sunbathers so all surfaces get exposed. Then the bricks are stacked and set aside. They’ll eventually be used to rebuild the bell tower over the church’s entrance.

“It’s all about community, participating in a traditional activity,” says Mike Green, a retired architect and chair of the Friends of the Ruidosa Church. “You see big smiles on their faces. That’s their inner child connecting with making mud pies, getting on their hands and knees, and shaping adobe by hand.

“People long for authenticity in their lives and something visible to show at the end of a day of hard work. Adobe-making gives us a deep feeling of achievement.”

Hilary Raney, a Marfa resident, mud enthusiast and gardener, spent her third Adobe Day, a mostly monthly event, providing a helping hand and moral support.

A view from the top of a hill looking south toward Mexico over the old church.

Erich Schlegel

Scaffolding inside one of the towers where the old adobe walls of the church have been structurally supported.

Erich Schlegel

Date palms outside the church.

Erich Schlegel

“I see new faces every time,” she says. “Last month a man in his 80s, whose parents got married in the church, came to Adobe Day. He was so happy to see what we were doing.”

Adobe-makers come from El Paso, Houston, New Mexico and, like Steve McKeon, from Oregon. After McKeon opened a restaurant and bar in Marfa, he decided to help make bricks. “Working bubbles out of a block by hand gives you a sense of accomplishment,” he says.

The Friends pays the bills for the church, power for which is provided by Rio Grande Electric Cooperative. Co-op power keeps the mortar mixer turning and the diamond saw spinning as it cuts adobe into segments.

Funds from the nonprofit’s Community Day fundraiser every November in Ruidosa help pay to transport blocks to the remote site and to bring in masonry specialists to install them. Grants from the Texas Historical Commission and the Summerlee Foundation cover the costs of a historic structure report that guides its preservation.

Conversations with earthen-structure professionals, architects and archaeologists set the stage for the site work.

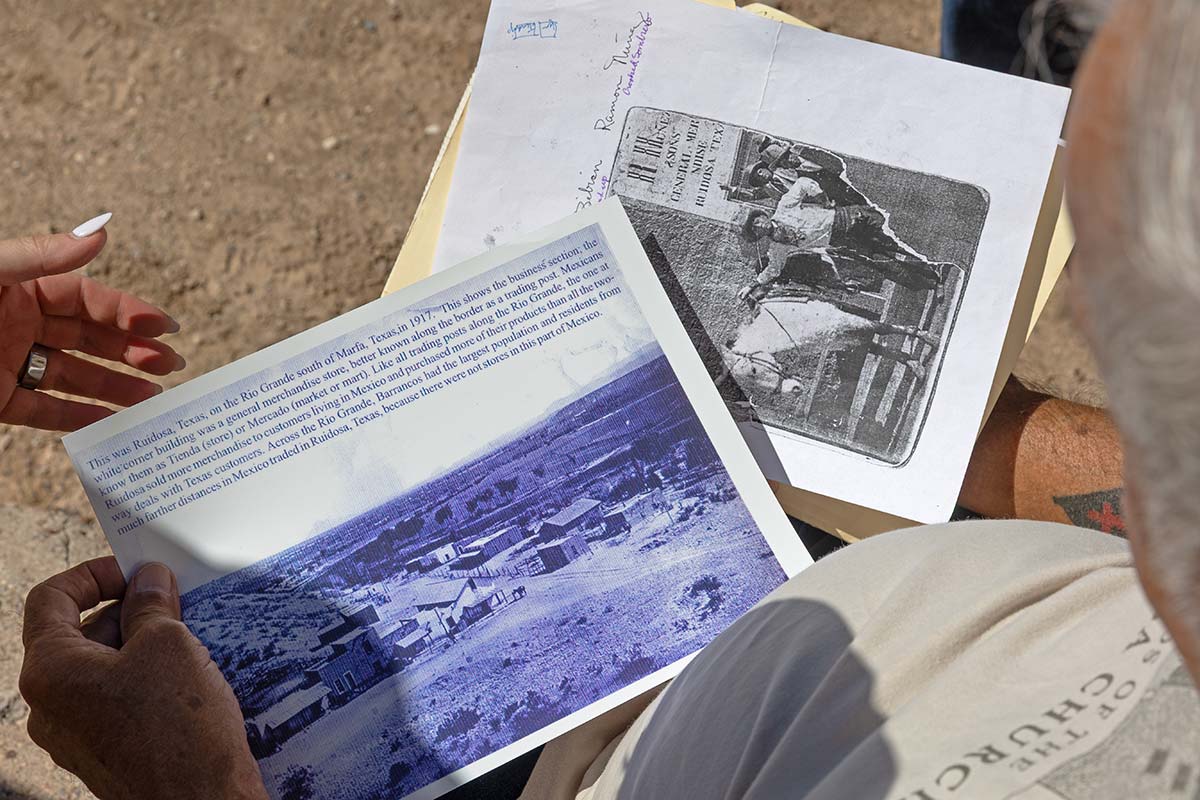

Ruidosa photos from the early 1900s.

Erich Schlegel

In 2023, Benton and his skilled crew began critical structural repairs to the church. They stabilized the foundation and installed scaffolding and support frames. They straightened a wall and saved the northeast tower from collapse by repairing adobe blocks and inserting new volunteer-made bricks as needed. In some areas the exterior was so worn that light was visible through the mortar joints.

Green praises Benton and archaeologist David Keller for their contributions to the preservation and restoration efforts.

“The earthen-structure community has no secrets or hidden techniques,” Green says. “We’re on the same journey: trying to restore and save adobes of the Southwest.”

Free for the asking, the adobe recipe mixes clay, sand, silt, chopped straw and water in proportions determined by the soil used. Clay comprises 15%–30% of the mix, acting as the binder, similar to cement’s role in concrete. The majority of the mix is sand and aggregate. Straw allows the adobe to dry more evenly by letting water get out of the block. The mortar has the same mix as the block but with finer aggregate.

This classic frontier Catholic church, with its substantial bell towers, is a time capsule for the community, says Keller, who is a Friends co-founder and preservation specialist. The church is unique in that the exterior was never plastered—rare for adobe structures, even in arid climates.

From left, Martha Stafford, Green and Grace Mortell work at the church.

Erich Schlegel

Nevertheless, while the church is being restored with historical accuracy, “the integrity of the structure and preservation guidance trumps absolute historical fidelity,” Keller says. So the exterior will be plastered to keep it from deteriorating like it did over the last 100 years. The interior, originally plastered and whitewashed, will be restored to that state.

Green hopes the bell will be restored to the entrance tower next year. In three years, he foresees the restored church telling the rich history of the area as a community center for residents of Brewster and Presidio counties as well as Ojinaga, across the Rio Grande.

Hands molding clay into architecture have built their own adobe-loving community. At the same time, they have helped restore the heart of a last-century community down a dirt road along the river.

As Green drove around the area over the years, the building often caught his eye. Eventually, his passion for architecture and history prompted him to try to save the old church. Now, the restoration work goes beyond saving the physical structure.

“The church at Ruidosa is the most peaceful place I know,” Green says. “It is so remote, so quiet, so serene. It feels like good spirits are in the air.”