2023 is the 85th anniversary of our cooperative, a milestone for which we are very proud and excited! Please enjoy the historical account below, which may be a walk down memory lane for some. Many things were different in 1935, and although progress has prompted us to different standards of living 85 years later, many of the things you read below will bear a striking resemblance to headlines we hear today.

Excerpted from Raising Poles, Raising Standards: The Eighty-Year History of Midwest, Stamford, and Big Country Electric Cooperatives

Midwest and Stamford electric cooperatives merged January 1, 1999, to form Big Country Electric Cooperative.

Electrification of U.S. cities began in the late 1800s and became more widespread into the early 1900s. Although power stations and power lines were birthed across the country, rural America remained largely in the dark, deemed an unprofitable investment by investor-owned and municipal utilities. “Doubtless, after 1915, the utilities could have extended service to many hundreds of thousands of farms at a reasonable profit,” said Harry Slattery, former administrator of the Rural Electrification Administration. “The most advanced country in the world in the use of modern methods in industry and agriculture, the United States has lagged astonishingly in making electricity available to farm communities,” economist Robert Beall said. As late as 1924, only 2.6% of American farms received power from a central station.

Investor-owned utilities fought against government intervention aimed at electrifying rural America.

After the conclusion of World War I, farmers made louder demands that could no longer be ignored socially or politically.

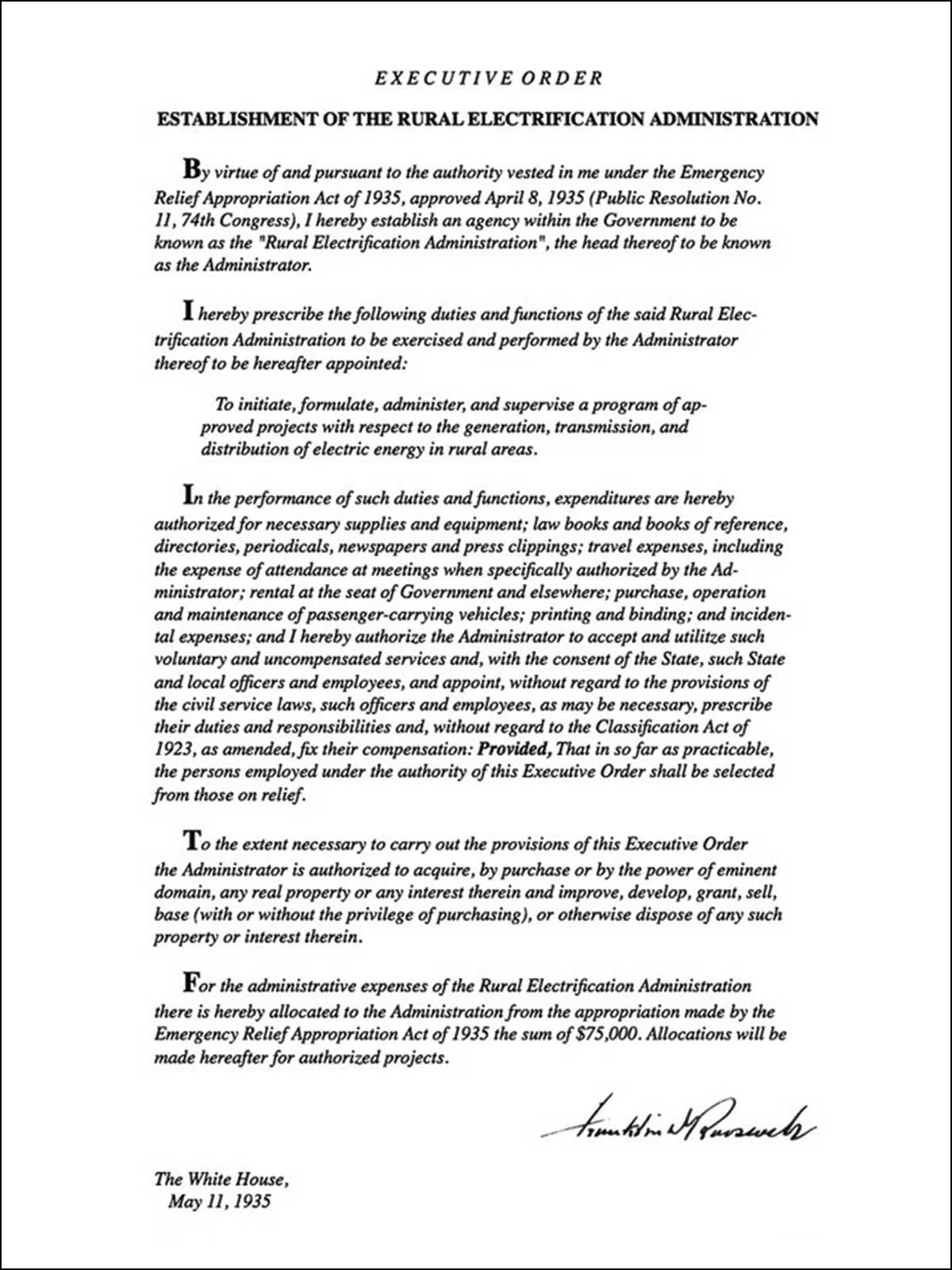

After more than two decades of fighting for electricity, May 11, 1935, was the date that would change rural Americans’ lives beyond measure. On that day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 7037, creating the Rural Electrification Administration. A longtime advocate of rural electrification, Roosevelt shared his vision for the future. “Electricity is no longer a luxury; it is a definite necessity … electricity and power made so cheap that they will become a standard article of use, not only for agriculture and manufacturing, but also for every home within reach of an electric light line.”

Nationwide, many bitterly denounced the order and called it socialistic; others praised it and sang the merits of such a magnificent cause. On May 20, 1936, FDR appropriated $100 million in funds for rural electrification, which the REA would oversee the distribution of. The REA was established as a lending agency of the federal government, providing both engineering and financial support while prioritizing loans to nonprofit organizations, along with the following provisions:

- Loans were extended in 25-year terms for the construction and operation of power plants, transmission and distribution lines to furnish electricity to those in rural areas without electric service.

- Loans could also be made for home wiring and plumbing and for the purchase of electric appliances.

- The REA would administer programs and services on a nonpartisan basis.

- Though often not discussed in as great a depth as many other historic turning points, the extension of electric lines into rural America brought about a great social transformation. Rural electrification brought rural areas into modern times and established a framework to power homes and move the nation forward.

Across Texas and the nation, crews of local men and boys would pile onto flatbed trucks and ride to work sites. Hacking brush and axing trees underneath the hot sun, they dug holes deep into the stubborn soil and rock to set poles and string copper wire across them. Mothers, wives and daughters prepared meals to nourish and support the workers and show appreciation. Though performing the work and meeting expenses was a mountainous feat, ordinary people came together to accomplish something extraordinary.

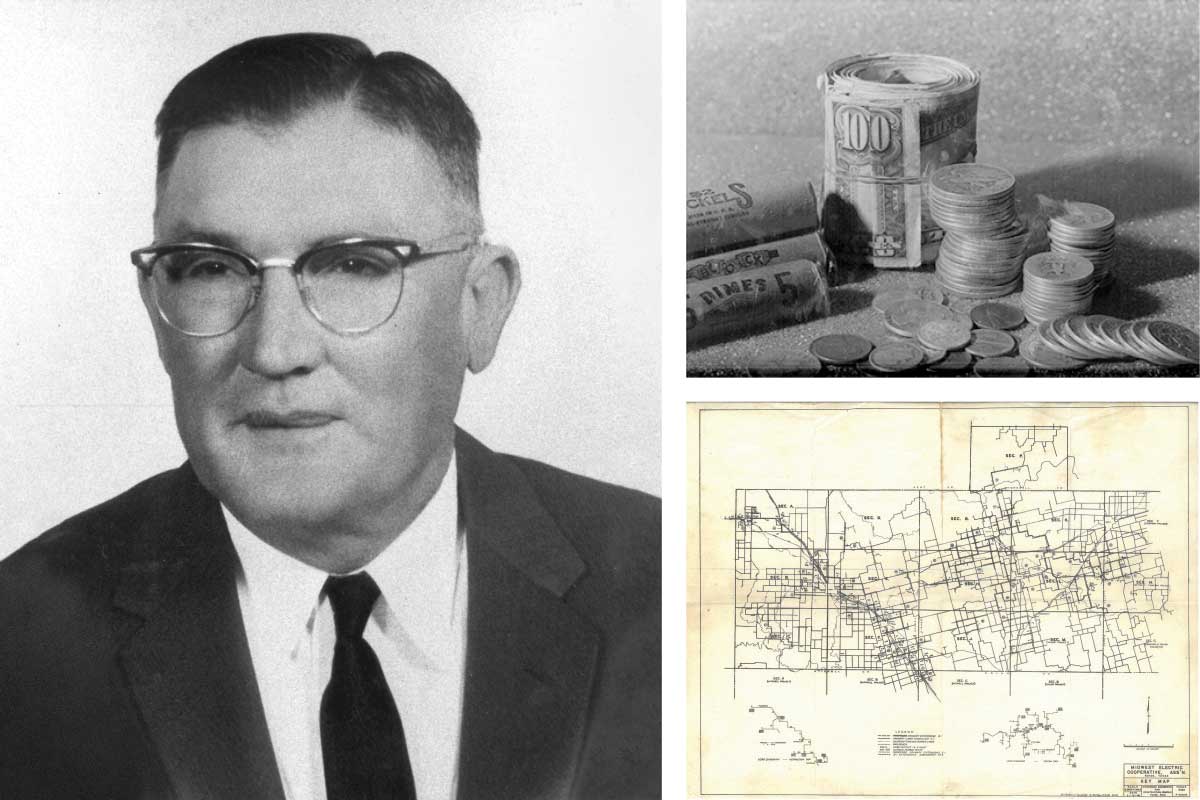

Midwest Electric Cooperative Is Born

In Fisher and Scurry counties, most folks were wary of rural electrification, believing it an unaffordable luxury that would never arrive. They were also dubious of the safety of electricity, said Andrew Willingham, son of Fisher County rancher Sterling Willingham, who pioneered Midwest Electric Cooperative. Willingham had a 32-volt gas generator that was giving him a lot of trouble that quit again the afternoon of June 10, 1938.

“We would start it for lights at night,” Andrew Willingham said. Electric service was on his father’s mind when he attended the Hobbs school board meeting that evening and raised discussion of the new REA loan program with other board members, who decided to pursue a loan.

Early logos used by Midwest EC.

Willingham sought the help of Hobbs agriculture teacher Cleveland Littlepage, who was known to love people and work to advance rural areas in any way.

“He was a master of all things,” Andrew said. “He took care of cattle when we couldn’t get a vet, handled the discipline at school—he did everything!” The next morning after the school board meeting, Littlepage began buttonholing everyone he encountered about the matter. He and Willingham hosted two countywide meetings to publicize the venture and seek donations to help the cause of rural electrification: 15 people were present at the first meeting, and 11 attended the second. A total of $13.11 was collected when Littlepage passed his hat.

Willingham’s son Andrew was about 10 years old during all this activity. More than 75 years later, his memories of rural electrification remained vivid. Andrew eventually became a professional engineer.

Joe Fender, a young Fisher County attorney, worked with Littlepage toward securing a charter for the cooperative, with the understanding that he would not be paid unless the charter was granted. On September 23, 1938, in Austin, Fender and Little-page were granted the charter for Midwest Electric Cooperative, named for its location in the midwest portion of Texas.

The first members and board of directors were the same group of seven: President Sterling Willingham of Hobbs, Vice President Homer Aaron of Rotan, Secretary Louis Singley of Rotan, Treasurer O.O. Hollabaugh of Roby, Ernest Kiser of Sylvester, James Beavers of Camp Springs and Julius Edwards of Rotan.

The first few months, a struggle to complete the loan application ensued. After the official incorporation in October 1938, each director was assigned an area in which he would visit the residents and try to sign them up as members, collecting a $5 deposit—an amount which was a struggle for most families to come up with. Some were afraid of electricity, fearing it would attract lightning to their homes. About 10–12 people, including the initial board and organizers, “spent many free hours to organize [the cooperative] and convince people [electricity] was safe,” Andrew said. Smiling, he reminisced about how “Highway 180 was Highway 36 back then, and just a gravel road. Town was always busy. People would bring cream, eggs and milk to town to sell for cash to buy groceries for the next week. Rotan had an icehouse, two gins, one or two barber shops, movie theater, locker plant, cottonseed oil mill, Ford and Chevy dealerships, and you could get a hamburger at Mercer’s for five cents. The gypsum mill was a big rail shipper—the line went east of Hamlin.”

After the articles of incorporation were approved at the co-op’s January 9, 1939, membership meeting, 132 members signed up for service and the newly formed organization set out to build 43 miles of line upon receipt of $137,000 in loan funds at 2% interest from the REA. They sought members then rights-of-way. It took them close to a year to get rights-of-way—some people didn’t want lines near their property and the co-op didn’t pay anything for the rights-of-way. The first lines were built in Fisher County near Rotan and Roby, through Hobbs, Sylvester and toward Hamlin to the Jones County line. The first service was on a farmhouse, not much load, mostly just lights.

The first meetings were held at Rotan City Hall until February 1939, when Virgil “Guy” Patterson, then president of First National Bank in Rotan, rented the co-op space to serve as its first office.

“I remember all the first board of directors,” Andrew said. “They met every Saturday morning at the First National Bank building in Rotan … for about six to eight months in a row. I would get an ice cream and a comic book and sit in the car during the meetings. They would last into the afternoon when planning lines and soliciting members.”

The co-op’s first permanent office building was completed in Roby in 1941 at a cost of $10,641—well under the $15,000 that had been budgeted. It housed offices, a warehouse in the back, a pole yard and an upstairs meeting room.

Logos used by Stamford EC.

Stamford Electric Cooperative Is Born

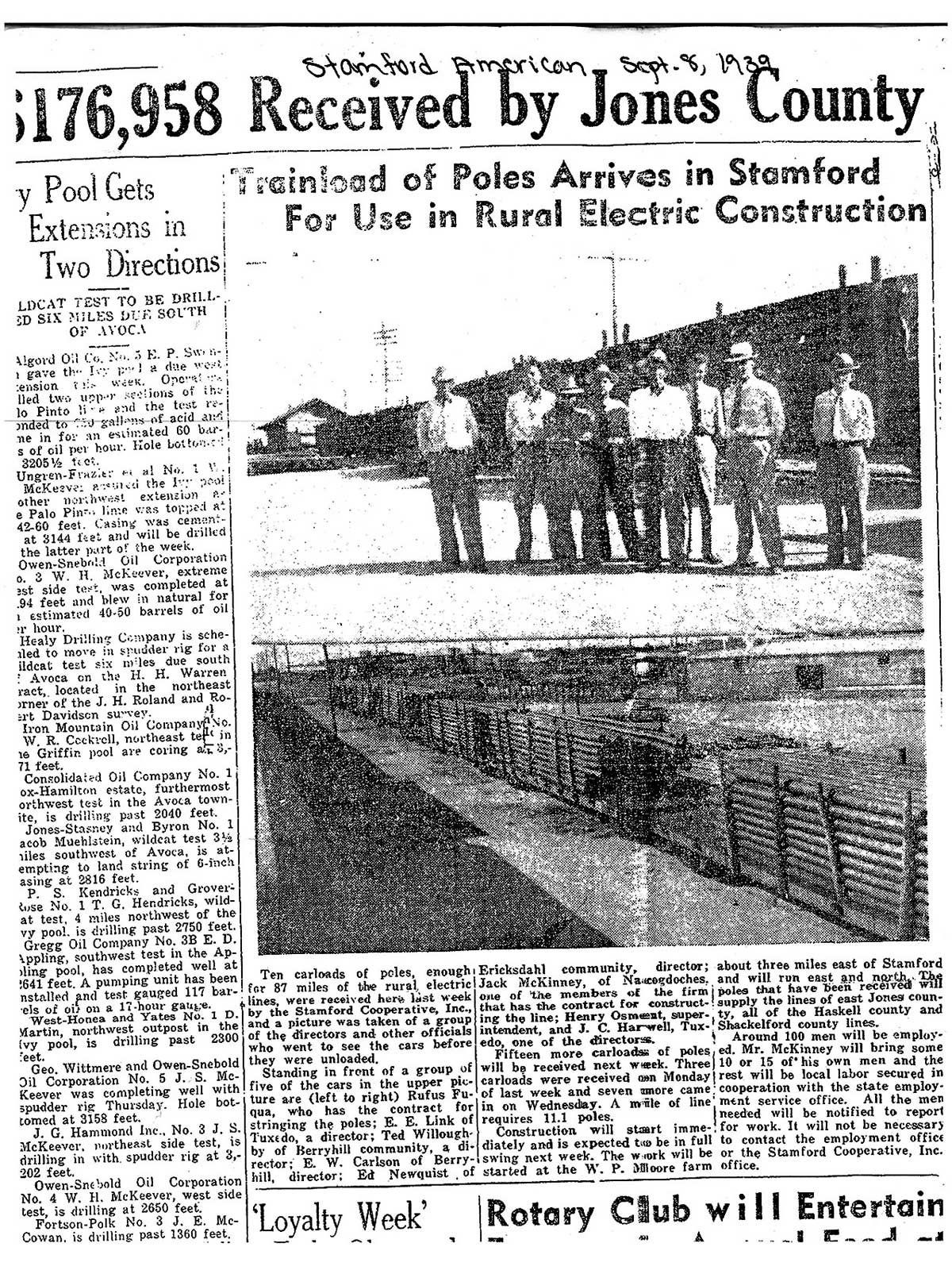

The “original five,” G.J. Smith, H.L. Osment, Hugo B. Haterius, W.H. Overton and H.G. Andrews Sr., began working without pay toward the goal of bringing electricity to the rural areas around Stamford. Confronting all hindrances, the articles of incorporation of Stamford Electric Cooperative were approved March 8, 1939, and the organization’s charter was granted six days later. The first official board of directors meeting was held March 16, 1939. Board members were Hugo B. Haterius, president; W.H. Overton, vice president; G.J. Smith, secretary-treasurer; H.G. Andrews Sr., attorney; E.W. Carlson; Ed Newquist; E.E. Link; Arche Pardue; and Ted Willoughby.

The old Hardy Motor Co. building was the first home of Stamford EC.

Stamford was abuzz with curiosity and excitement as poles began arriving on railcars. This photo and story were on the cover of the Stamford American newspaper September 8, 1939.

The first office for the co-op was at the southeast corner of McHarg and Ferguson streets, a shared space that was offered rent-free by the Stamford Production Credit Association in the old Hardy Motor Co. building, until it became feasible for the co-op to have its own office building.

In April 1939, H.L. Osment was hired as project superintendent for a salary of $150, with car and travel expenses to not exceed $50 per month. He would oversee construction of the A section, which was 136 miles of line that went north from Stamford almost halfway to Haskell, then to Paint Creek; Rockdale Community; New Hope; Swan’s Chapel, just north of Anson; Hanna Community, just beyond Tuxedo; and to Sagerton.

In July, the REA approved Stamford Electric Cooperative’s $158,000 loan application for the A Section at 2.69% interest on a 25-year term.

Upon the loan’s approval, construction on the A Section progressed rapidly and on November 23, 1939, the line was energized. Between that date and December 31, 1939, 369 members were billed an average of $1.72 for an average use of 15 kilowatt-hours.

In the latter months of 1939, a half-ton Chevrolet pickup truck was purchased for $580. In December, the board authorized Christmas decorations for the office, an expenditure that was not to exceed $10. Progress continued to be made and in January 1940, the co-op was able to pay for rent and basic utilities. Rent was $20 per month, heat and water were $13, and electricity was $2.70.

In October 1940, the co-op contracted to construct B Section—265 miles of new line. For $695, the cooperative purchased a fully equipped Plymouth Business Coupe, with seat covers and a heater, for the superintendent from Prewit Motor Co. In May 1942, salaries were increased $5–$15 per month due to increased cost of living.

July 1942 marked the co-op’s first prepayment to the REA on loan funds, and in 1943, the co-op showed its first profit, allowing for improvements to be made to the electric system. The first automatic oil circuit reclosers were installed to assist in preventing power failures. Many power failures were due to some conductors failing; the matter was addressed with the manufacturer, who agreed to pay the cooperative $15,000, which was used to correct the faulty conductors. In July 1945, the board approved purchase of a power hole digger for $7,500.

The possibility of increased power costs loomed, concerning Stamford, Midwest, Taylor and Coleman electric cooperatives, which led to the formation of Mid-Tex Generation and Transmission Cooperative (now Golden Spread Electric Cooperative), and the idea of building their own generation plant.

In 1949, two-way radio equipment was installed to allow for communication between the trucks in the field and the office. C.M. Lester said in his memoir: “A lady had just called the office to report that the power was off, and glancing out the front door, saw the lineman climbing the pole in front of the home. It had happened that the lineman was a short distance from her home when he received the call.”