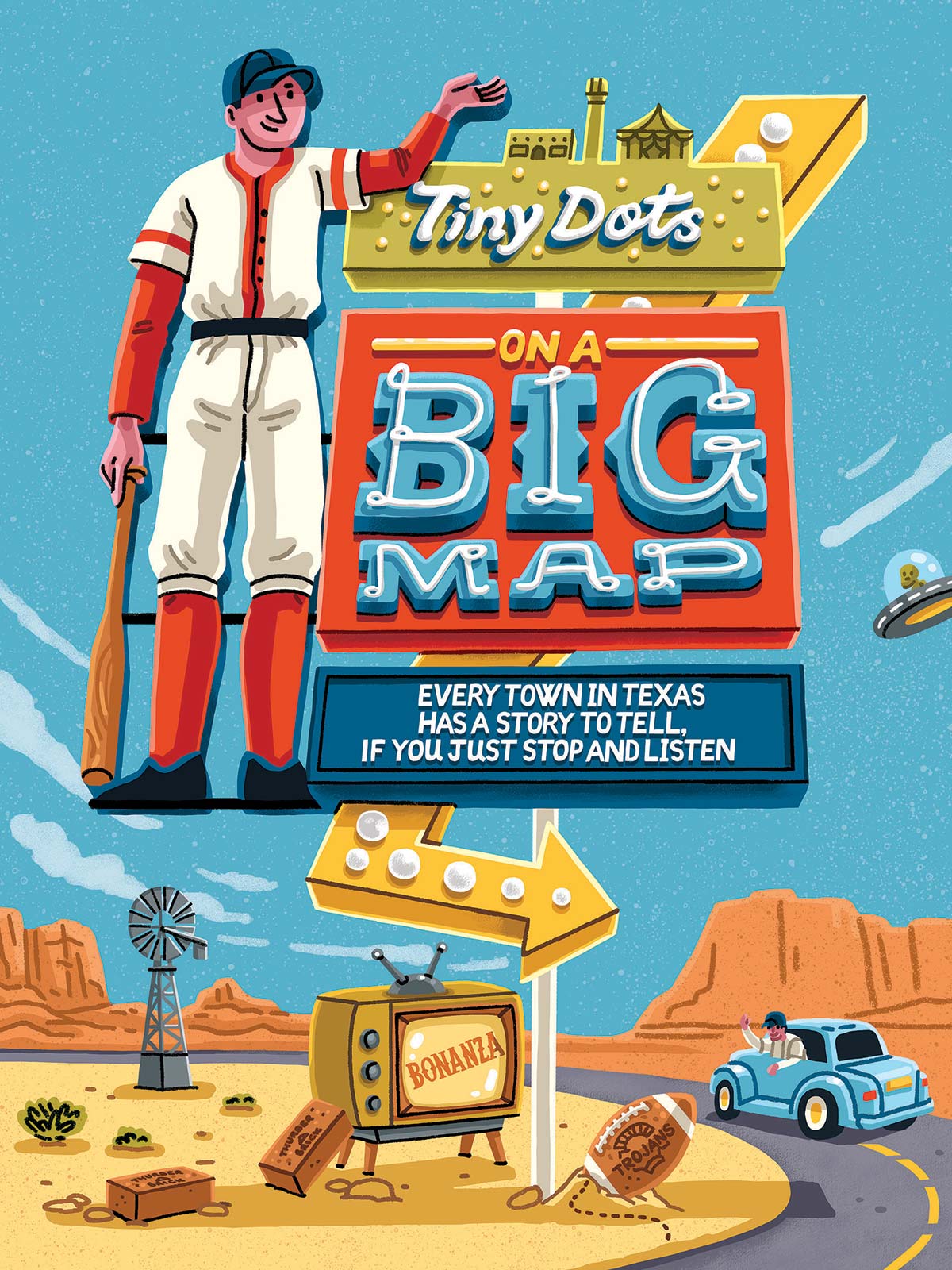

Even lifelong Texans haven’t heard of many of these towns. They are hidden along isolated country roads, mostly forgotten, without stoplights, traffic jams or shopping malls. Truth be told, they have precious little reason for “being” aside from the fact that those who call them home wouldn’t trade for all the big-city comforts you might offer. And they each have stories to tell—colorful, poignant and fascinating.

The following are a few of the favorite stops I’ve made over the years while wandering the state’s back roads in search of yet another tale to tell.

Pelham

Navarro County | Population 35

A Former Freedmen Community

When I met him in 2012, 88-year-old Alfred Martin, the self-appointed town historian, lived across FM 744 from what was once the school he attended as a boy. Aside from the time he spent as a flight line crew member for the legendary Tuskegee Airmen during World War II, this was Martin’s home.

He could recall when the state’s last remaining all-Black community boasted a grocery, dry goods store, church, post office and a population of more than 300. Pelham even had an amateur baseball team that brought home a state championship.

Asked the current ages of his neighbors, Martin smiled and began pointing in the direction of their houses and counting: “Let’s see … 88, 93, 85 …” Pelham, he admitted, wasn’t likely to make it much longer.

When the Emancipation Proclamation freed the nation’s slaves following the Civil War, each Black man in town was given 200 acres to call his own. Fields were cleared and tilled, cotton and grain planted, and new lives thrived.

Now, however, the community’s well-tended cemetery is the resting place of the majority of past Pelham residents. The aging memorabilia and family histories housed in the school-turned-museum keep alive the memories of better days.

Elly Walton

Hye

Blanco County | Population 100

The All-Brothers Baseball Team

Inside the combined Hye General Store and Post Office, a fading black-and-white photo hangs proudly behind the checkout counter. Nine Deike brothers, dressed in spanking new baseball uniforms, smiling for the camera.

It was snapped during the Depression doldrums when leisure time was as scarce as spending money. An endless routine of work awaited on the farms and at the cotton gin. Only on Sundays did the residents take time off to watch their baseball team play rivals from nearby rural communities.

It was called town ball, and it was generally played on makeshift diamonds carved from pastureland. The preacher would even cut his sermon short so members of his congregation wouldn’t miss the first pitch.

Only Hye, 60 miles west of Austin, could field nine players from the same family. Fourteen-year-old Victor was the youngest; brother Edwin, 34, was the oldest. That’s not to say they weren’t occasionally joined by nonfamily members. Regularly, a lanky first baseman named Lyndon Baines Johnson would drive over from nearby Johnson City.

In 1935, a traveling salesman learned about the Deike brothers and hit on a can’t-miss promotional idea. If he could find another all-family team, his Corpus Christi-based Nueces Coffee Co. would promote an exhibition game deciding the All-Brothers Baseball Championship.

Indeed, an opponent was found in Waukegan, Illinois. There, the Stanczak clan had 10 brothers on the same team.

The game would be played in Wichita, Kansas. Provided with their first uniforms and travel expenses, the Deikes made the 14-day trip to Kansas in two Model A Fords. The Stanczaks arrived by bus.

Alas, a perfect ending to the Hye brothers’ story wasn’t to be. Though they took an early 3-0 lead, the more talented Waukegan team eventually won 11-5. Today, it is their picture on display in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Still, for the Texas farm boys, it was a time that would long be remembered. A special time, right up there with the day President Johnson came back for a visit to stand in front of Levi Deike’s post office and swear in Lawrence O’Brien as the new U.S. postmaster general.

Thurber

Erath County | Population 48

When Even the Circus Came to Town

In the late 1800s, Thurber was the most populous town between Fort Worth and El Paso, boasting 10,000 residents. Today, travelers hurrying along Interstate 20 see only a solitary smokestack standing watch over its history.

The only reason to stop is for the home cooking served at Andrea Bennett’s red brick Smokestack Restaurant. Inside, the walls are lined with photographs from another time, back when her restaurant was the local mercantile and the townspeople were mining 3,000 tons of bituminous coal and firing 80,000 bricks daily.

Workers and their families came to live in the small frame houses provided by the Texas & Pacific Coal Co. There was a school, a 650-seat opera house, general store, fire station, churches, a weekly newspaper, library, hotel, and a human-made lake for fishing and swimming.

The Thurber baseball team, made up of miners, won the 1896 Texas amateur championship. Each summer a traveling circus came to town.

Thurber bricks were used to build the Galveston seawall and pave many of Fort Worth’s early streets. Its coal kept the trains running and homes heated.

Though the exact date isn’t official, Thurber died in 1936. The oil boom was the killer, its black gold replacing coal as the nation’s favored fuel. The mines began closing, and workers scattered in search of new jobs. The frame houses they had called home were sold off for $40 each to anyone willing to haul them away.

Now all that remains are the ghost stories, the nostalgic pictures on Bennett’s restaurant walls and the nearby 100-year-old town doctor’s house where she lives.

Elly Walton

O’Donnell

Lynn County | Population 704

When Hoss Was Just a Colt

It is tradition, you know, for small towns to alert passersby to the fact they were once home to somebody famous. Billboards are the favored tool. Even little Abbott had one to remind travelers that it was country music legend Willie Nelson’s hometown until, hoping to regain a sense of privacy, he set fire to the sign late one boozy night.

To my dismay the Panhandle community of O’Donnell, just south of Lubbock, had not gotten around to any side-of-the-road celebration of its favorite son.

Back in the Bonanza heyday, TV Guide expressed interest in learning how this cotton crop way-stop had groomed famed actor Dan Blocker to become the good ol’ boy Hoss Cartwright on the popular TV show. I hit the road.

And the townspeople were ever so obliging. Seemed almost everyone I bumped into went to school with Blocker, played football with him, fought with or dated him. Even those who didn’t know him firsthand insisted they were faithful viewers of his portrayal of Hoss every Sunday.

Yet friend and farmer Wayne Carroll admitted Blocker’s TV role puzzled him. “It’s kind of hard to picture Dan on the Ponderosa,” he said. “Farming and ranching never interested him. He was the guy we all went to for help with our lessons, always studying or reading a book.”

His mother, Mary, agreed: “One Christmas we got him a horse and saddle, but he really wasn’t interested. After a while, we sold the horse.”

When her son didn’t have his nose in a book, he worked weekends at his dad’s Blocker Grocery & Market. On Friday nights, he was a standout lineman and kicker for the O’Donnell Eagles. The only kid in town who could lift the rear end of a ’47 Plymouth, his strength and size (already 6 feet tall and 200 pounds by age 13) earned him a scholarship to play for what was then Sul Ross State College in Alpine.

Once Blocker earned his degree, his life’s goal was to become a teacher. He did teach for a time in high schools in New Mexico. But then Hollywood and the fictional Ponderosa beckoned.

Rest assured, Blocker never forgot his roots and came to visit regularly. At the height of his acting career, he even made an appearance at the annual O’Donnell Rodeo. “Biggest crowd we ever had,” recalls boyhood pal Bobby Clark.

With the exception of cotton crops, I learned that conversation is O’Donnell’s main byproduct. And the easiest way for a stranger to be assured a generous helping of the latter is to bring up the name Dan Blocker.

“There was once some talk about a billboard,” Clark says, “but the more we thought about it, the more convinced we were that Dan wouldn’t care much for the idea.”

Elly Walton

Aurora

Wise County | Population 1,390

Long Before Roswell

The story was right there on the front page of The Dallas Morning News in April 1897, so it had to be true, right?

S. E. Haydon, the paper’s longtime correspondent, had written of an “airship” that flew over the North Texas community of Aurora before crashing into Judge Proctor’s windmill and exploding. Aluminum-like debris, Haydon wrote, was scattered everywhere, destroying the judge’s water tank and ruining his prized flower garden.

Bear in mind, this report was filed a decade before the Wright brothers got their rickety plane off the ground at Kitty Hawk and predated, by half a century, that famous Roswell, New Mexico, report of the ranchland UFO crash that became the gold standard of otherworldly tales.

And the Aurora story got even better. The child-sized pilot of the craft had been killed in the crash, and kind citizens of the community saw to it that he was given a proper burial in the nearby cemetery the following day. The grave was marked by a large rock featuring a quickly sketched image of “a cigar-shaped ship with three circular windows.”

Today a historical marker stands at the entrance to the cemetery, recalling the event.

Is the recounting true or false? People have been asking for over a century. Some say Haydon had a habit of telling whoppers when there was no real news to report and he just invented the spaceman’s visit.

But as late as 1973, an aviation journalist named Bill Case visited the community and tracked down a 98-year-old local who recalled visiting the crash site as a child, even viewing the “torn-up body” of the spacecraft’s pilot.

At the time, the makeshift headstone was still in place. Case even took a picture of it. But soon after his article was published, the marker vanished. Today, no one in Aurora is certain of the exact location of the infamous grave.

Legendary investigative reporter Jim Marrs, who spent his career researching the strange and spooky, says he was, for years, “undecided” on the matter. In time, however, he found the story compelling enough to produce a full-length documentary on the alleged crash.

“What ultimately got me off-center on the matter,” he says, “was seeing the actual edition of the paper in which Haydon’s story was published. It wasn’t even the lead story that day. Among numerous accounts of strange sightings was one from nearby Stephenville, headlined The Great Aerial Wanderer. In all, the newspaper published 16 stories about UFO sightings that day, from as far south as Austin and north into Oklahoma.”

Something, he was convinced, really did happen in Aurora.

Strawn

Palo Pinto County | Population 540

Magic at Mary’s Cafe

Neither a food critic nor avowed foodie, fine dining and haute cuisine are foreign to my vocabulary. That said, it is my humble opinion that the Michelin Guide folks have missed a bet. Or maybe they just have something against chicken-fried steak.

In the tiny hamlet of Strawn, just 90 minutes southwest of Dallas, is the mother church of the popular comfort food. At Mary’s Cafe every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas, the service station-turned-eatery is jam-packed. The gravel parking lot is filled with traveling biker clubs, church groups or a busload of young athletes in search of a post-game meal.

Owner Mary Tretter estimates that over 90% of her customers are from out of town, arriving from as far away as New Mexico, Colorado and Georgia. Some come wearing the Mary’s Cafe T-shirts they purchased on a previous visit.

And while the menu is lengthy and varied, it is the king-sized chicken-fried steak with a bowl of cream gravy and a mound of french fries that is most often requested. Annually, Tretter orders over 48,000 pounds of cutlets that are pounded, floured and cooked into her signature dish.

But don’t bother asking for the recipe. It is so heavily guarded that she requires her 30 employees to sign a nondisclosure agreement before stepping into her kitchen. All she will admit is that her chicken-fried steaks are cooked on a flat-iron griddle rather than heavily battered and actually fried.

Tretter was 14 when she started working there as a waitress and dishwasher. The place was known as the Polka Dot then and was struggling mightily. The local bank, preparing to take it over, asked Tretter if she might be interested in buying it. At the time she was neither business savvy nor much of a cook but bought the little 89-seat restaurant.

That was in 1986.

She changed the name, hired a staff and went to work. In her fourth decade of ownership, seating capacity is 300—and getting a table isn’t without a little wait.

And Tretter gives “hands-on” new meaning. She takes Wednesdays off to spend time with her grandkids. The rest of the week she’s in the kitchen cooking or out on the floor, greeting customers and taking orders.

“Our goal,” she says, “is simple: Fill the plate with good food, make it look nice and keep the customers happy. If they leave here hungry, it’s their fault.”

Elly Walton

Asherton

Dimmit County | Population 722

Fleeting Victory

I’ve always loved the scene in the movie The Big Chill when a reporter explains that he’d just been assigned to do a feature on a blind baton twirler. When asked where in the world such story ideas come from, he shrugs and answers, “Just good investigative reporting.”

Personally, I prefer the magic of dumb luck.

To wit: I was awaiting a flight home from Houston, reading the sports section of the local paper, when a small item caught my eye. Asherton High School, it noted, had just won its first basketball game in years. The final sentence added that the same school’s football team currently owned the nation’s longest losing streak.

Two things immediately occurred to me. First, I had to figure out where Asherton was. Second, what publication would be interested in a story on such a historically hapless team?

The editor of Parade magazine bit, and I was soon off to deep South Texas. By the time I arrived, the Trojans had lost 40 football games in a row. A few years earlier, they had endured an entire season without scoring a single point.

Yet what I found was light-years from what I’d expected. A migrant worker community, it was virtually deserted since most families had not yet returned home from following the northern harvests.

The school was in disrepair, jagged cracks in its old brick walls, the 500-seat stadium in worse shape. There was little grass and a huge ant bed spread across the 50-yard line. The scoreboard was a hand-me-down, donated by neighboring Carrizo Springs. A 24-year-old teacher, Terry Harlin, who never played the game, had agreed to coach since no one else wanted the job. School officials agreed to add $600 to his salary for the extra work.

Thus, the story was not one of laughable ineptness but, rather, a courageous quest against impossible odds.

Readers took the plight of the Trojans to heart. Envelopes bearing small donations began arriving from across the nation. A Houston sporting goods company donated shoulder pads and helmets. Inmates of a Georgia prison adopted Asherton as “their team.”

And in the first game of the 1972 season, Asherton won, defeating rival Crystal City 12-6. A film crew, dispatched from a Houston TV station, was there to record the historic event.

The cheers, however, didn’t last. In 1999 the Texas Education Agency ordered Asherton High to close, citing its troubled history of financial insolvency. The students bade their old school goodbye and enrolled in the nearby Carrizo Springs Independent School District.

• • •

There are endless other nifty towns, like Study Butte, home of the last one-room school in Texas; Luckenbach, where legendary owner-mayor Hondo Crouch held court; Terlingua and its annual chili cook-off; and Cisco, where Conrad Hilton bought his first hotel and Santa Claus robbed the bank.

Get out your map.