What do you mean, which Big Bend? There’s only one Big Bend!

That’s true, geographically. The Big Bend is where the Rio Grande makes a 100-mile end-around of the Chisos Mountains on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. This Big Bend encompasses three majestic canyons—Santa Elena, Mariscal and Boquillas—all within the 801,000-acre Big Bend National Park.

That’s the Big Bend most folks have been talking about since the national park was established in 1944.

Now, Big Bend also refers to the neighboring Big Bend Ranch State Park, a 311,000-acre spread west of the national park that first opened to the public in 1991.

My first encounter with the national park was a visit at age 8, when I was immediately awed by the Chisos Mountains and javelinas. Since then, I’ve paddled all three canyons as well as the Lower Canyons, hiked 80 miles from Rio Grande Village to the town of Lajitas and completed the 14-mile round trip to the South Rim with my family.

I started visiting Big Bend Ranch as soon as it became accessible. I’ve paddled Colorado Canyon, hiked 14 miles from the Lower Shutup to near Lajitas, bushwhacked to Madrid Falls and spotlighted scorpions with a black light while taking a desert survival course.

The Big Bend encompasses two major parks and three inviting towns.

E. Dan Klepper

The state park is most definitely part of the geographic Big Bend. That was easy to see flying over the region in a Cessna named Brownie piloted by Marcos Paredes of Rio Aviation in Terlingua. The bending of the Rio Grande starts in Colorado Canyon, which forms the southern boundary of the state ranch, long before the river reaches the national park.

But visitors, especially first-timers, still ask: Which Big Bend?

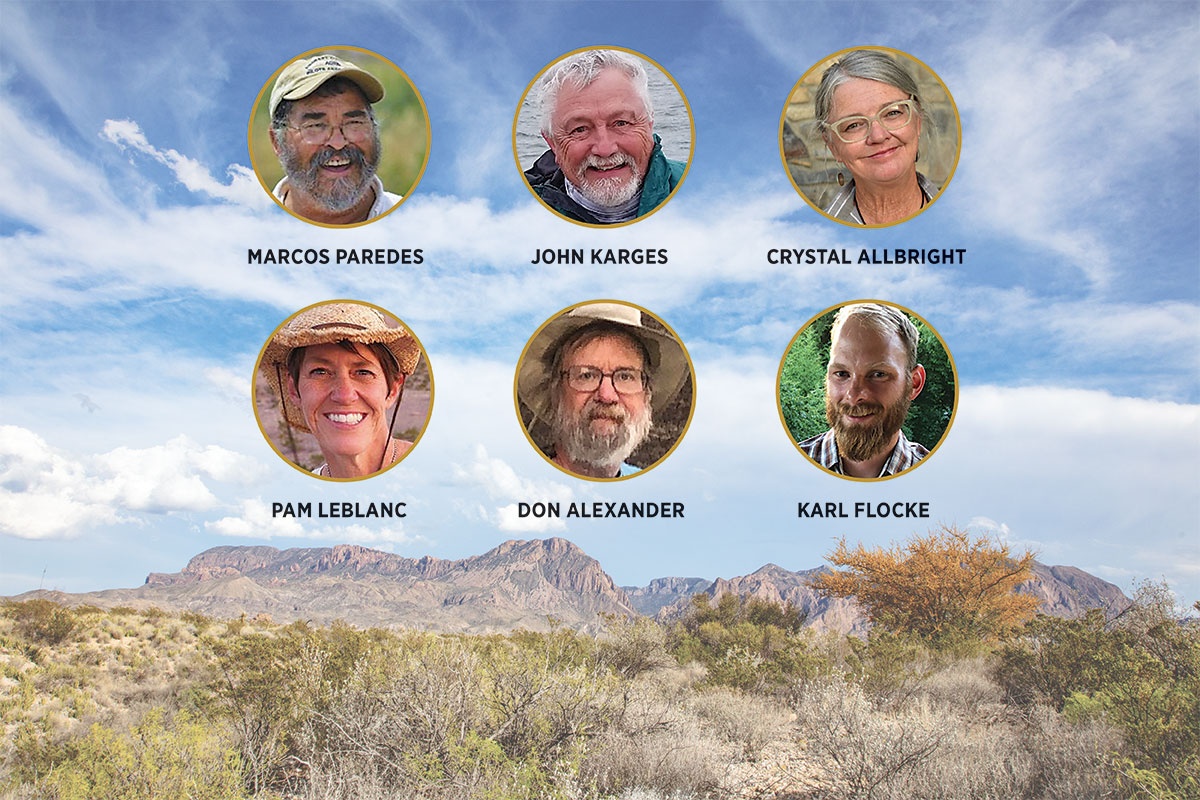

When asked, six people who know the region well, starting with Paredes, a retired river ranger for Big Bend National Park, had some answers. “What separates the state park from the national park is live water,” he says. “That’s what stands out as you fly over this country. The cottonwood bosques and the live streams scattered throughout the arroyos and canyons of the state park are conspicuous and their absence is glaring as you come over the national park.”

Big Bend Ranch State Park is loaded with 118 springs, seeps, tinajas, and Texas’ second- and third-highest waterfalls. The national park has hot springs to soak in, 100 miles of the Rio Grande, a hidden waterfall and Ernst Tinaja—a natural pool, campsite and trail.

Big Bend National Park with the Chisos Mountains, is considered more approachable than Big Bend Ranch State Park, with its sparse amenities.

E. Dan Klepper

“The Chisos [Mountains] are a lot higher than anything in Big Bend Ranch,” explains John Karges, a conservation biologist. “On the other hand, the Big Bend Ranch has the Solitario.”

The Solitario is a volcanic dome, a mile across, that emerged from a collapsed caldera, a wholly unique feature that doesn’t dazzle like the Window in the Chisos or the mouth of Santa Elena Canyon in the national park until you see it from above.

Big Bend National Park is nearly three times the size of Big Bend Ranch and more developed, with paved, RV-friendly roadways, big campgrounds, and a hotel and restaurant. The only paved road in the state park is River Road, FM 170, along the park’s southern boundary. State park campsites are primitive. “You have to bring your own water and carry out your waste,” Karges says. “It’s a little more of a rugged experience.” The sole alternative to camping is a bed in the bunkhouse at Sauceda headquarters and use of its kitchen.

Karges says the national park is tailored for windshield tourists—the majority of first-timers, who tend to stick to their vehicles. “You spend a day or two driving to the highlights at both ends and the [Chisos] basin,” he says of tourists who seek out Santa Elena and Boquillas canyons. On the other hand, “Big Bend Ranch, you really have to want to go there.”

Photographer Crystal Allbright lives and works between the parks and takes advantage of each. “If I want to go on a multiday river trip in a designated wild and scenic area, I head for the national park,” she says. “For mountain biking trails and a few dog-friendly areas, it’s the state park. If I have to choose hiking, camping or dark skies…well, then I might have to flip a coin.”

Courtesy subjects

Writer Pam LeBlanc from Austin leans ranch, which she visited six times in 2018, including for several multiday bicycle treks. “They are entirely different worlds,” she says. “I go to the national park for the South Rim. I can lay on my belly and peer down on a million miles of what looks like rumpled rhinoceros hide. Or I climb to my secret spot on Mesa de Anguila to take in the best view in the state. But when I feel scrappy and wild, like I need to get lost among the rocks and spiky things, I go to the state park. No one can find me there.”

The desert, the remoteness and the heat can test visitors of either destination. Don Alexander, a Big Bend regular from Waco, observes that the popularity of the national park makes it difficult to find absolute solitude, which he says is “one of the highlights of the Chihuahuan Desert.”

Big Bend National Park attracts about 400,000 visitors annually, peaking at around 8,000 daily. Big Bend Ranch State Park hosts fewer than 50,000 visitors, with 8,000 visiting the park itself, 28,000 stopping at the Barton Warnock Visitor Center in Lajitas and about 5,000 at the Fort Leaton State Historic Site at the western edge of the park, near Presidio.

Alexander’s most recent Big Bend adventures have been with his 75-year-old brother-in-law, who has mobility issues and a fear of heights. “That means 2-mile hikes with rocky scrambles, such as Upper Burro Mesa in the national park, are out,” he says.

Alexander found the state park campgrounds at Lower Madera Canyon and Grassy Banks, just off FM 170, to be less crowded than those at the national park but susceptible to sounds of passing traffic. He says they found “perfect desert silence” camping near Big Bend Ranch’s Sauceda headquarters, after driving 27 miles of rough gravel road to the center of the ranch.

Big Bend Ranch State Park

E. Dan Klepper

Karl Flocke’s idea of the ultimate Big Bend experience is “solo hiking through a remote canyon, rounding a bend to the next expansive view and wondering if I’m the first modern man to stand in this spot,” he says. “While the answer is most likely ‘no,’ I find it much easier to entertain these kind of thoughts at the state park.”

As a former law enforcement ranger at Big Bend Ranch, Flocke, now a woodland ecologist for the Texas A&M Forest Service in Austin, may be biased. But it’s not just him. “I can’t recall how many times I have heard people comment that the state park is how they remember the national park being ‘back in the day,’ ” he says.

Flocke nonetheless recommends experiencing the national park first. “This isn’t out of any attempt to scare people away or to suggest that the state park is only for people who are worth their mettle,” he says. “It is simply that the national park is much more approachable. The Chisos Mountains offer contrast of scenery for those who may not be wowed by desert expanses. There are more restrooms, more trash service, better trails, more ranger programs, convenience stores and restaurants. Intrepid hikers still have the opportunity to get off the beaten path, but no matter where you go, it seems like you are more likely to see people in the national park.”

Then try the alternative. “The gravel road into the center of the state park is a portal that transports you to an entirely different time and place,” Flocke says. “Something about that washboard road really disconnects you from the rest of the world. It lends a wilderness vibe to the park that is unlike anywhere else in Texas.

“First-timers, inexperienced family campers and RVers—go to the national park. Experienced family campers, backpackers, bikers, horseback riders and Jeepers—give the state park a try. Go there before it gets discovered.”

One factor that complicates comparisons is that each park operates differently. “The national park is federal and has more mandates, doctrines and management protocols than the Big Bend Ranch State Park,” explains Bonnie McKinney, wildlife coordinator at El Carmen Land and Conservation Company adjacent to the national park and a onetime Texas Parks and Wildlife Department employee. “They have similar rules and regulations, particularly pertaining to artifacts and historic sites, but differ on wildlife and land management,” McKinney explains. “Most national parks let nature take its course. Big Bend National Park doesn’t create water sites for wildlife. Big Bend Ranch has built water sites in remote areas for wildlife.”

Maybe the best answer to “Which Big Bend?” depends on which way you plan to enjoy exploring the region. Will you be driving through or staying a while? Does the next adventure involve a long hike in the desert or in the mountains, a short one-mile hike from the road, off-road bicycling or four-wheel drive, or a canyon paddle on the river? With all these options, the answer to “Which Big Bend?” really is “Both.”

Writer Joe Nick Patoski lives outside Wimberley and is a member of Pedernales Electric Cooperative.

Correction: August 30, 2019

This story was updated to correct the number of visitors Big Bend National Park gets annually. It’s about 400,000, not 4 million.