During the civil rights era, even basic human dignity had to be reaffirmed by the rule of law. In the mid-1960s, Congress confirmed that separate drinking fountains for blacks and whites didn’t make any sense.

The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin reminds us how important it is to remember and honor the struggle and sacrifice of those who worked, fought and died for change. Struggle for Justice: Four Decades of Civil Rights Photography is an exhibition of news photography in the recently expanded galleries of the Briscoe Center that offers a powerful collective eyewitness account of that turbulent time.

Located adjacent to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum on the edge of the university campus, the Briscoe Center offers exhibit space and a reading room, where visitors can peruse an extensive array of research materials from its many collections.

“We document the American story,” explains Don Carleton, the center’s executive director, “with a particular focus on aspects of Texas, the South, news media, politics and government.”

Author Stephen Harrigan can confirm that. Engaged in the colossal task of writing a new history of Texas, Harrigan says, “I can’t imagine how I could have managed it without the Briscoe Center. I’ve gone there time and time again to read obscure biographies and memoirs that no other archive has, or to look at stunning artifacts like Stephen Austin’s letters or Governor James ‘Pa’ Ferguson’s speech announcing his intention to run for office, written in pencil on his daughter’s borrowed school tablet.”

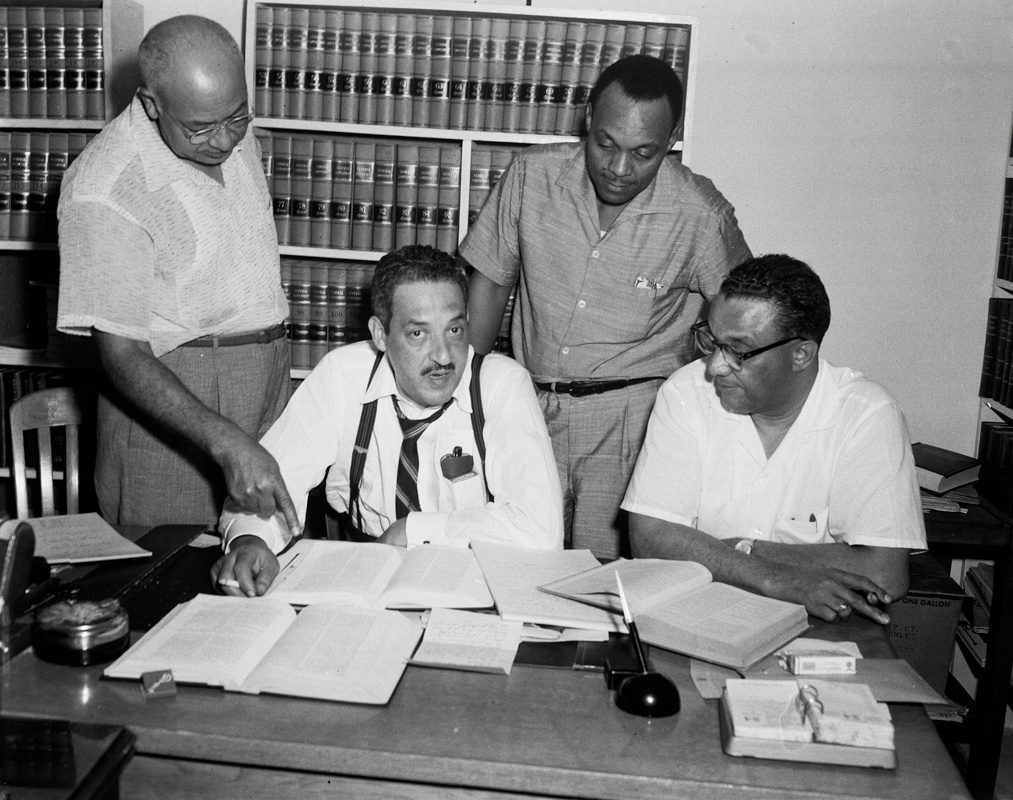

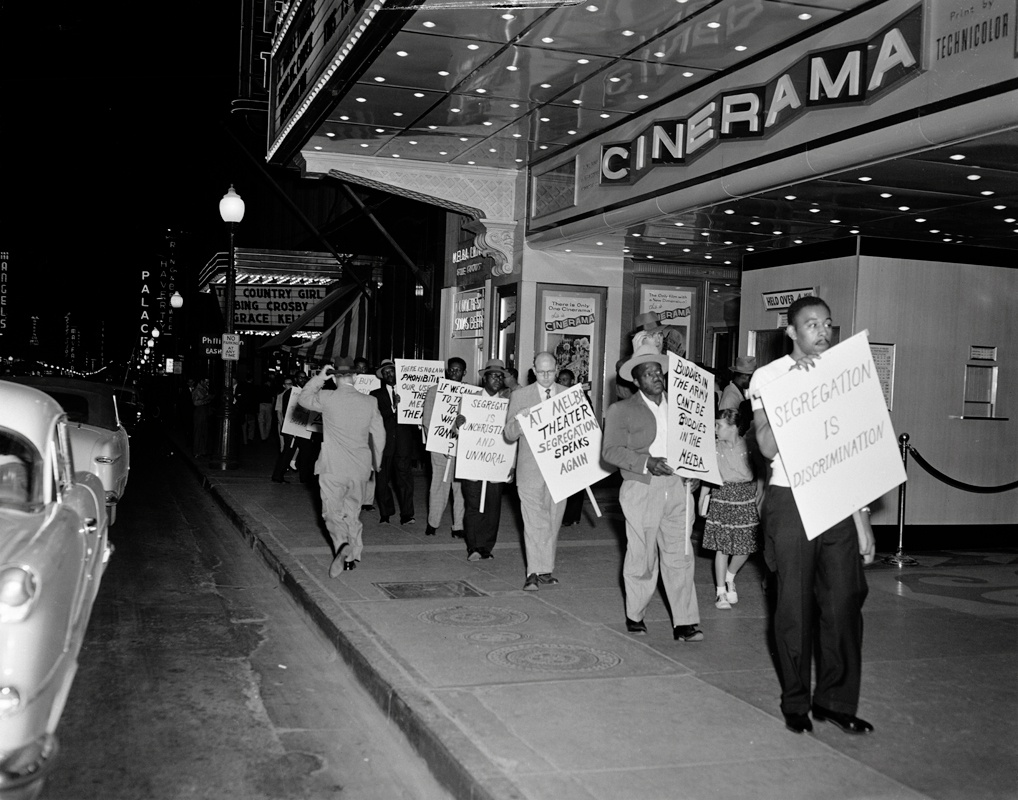

The expanded gallery space is where the center shares its rich trove of archival images, documents, artifacts and media. Struggle for Justice includes material selected from 35 individual Briscoe collections. Dramatic photographs capture scenes of landmark events in the struggle across the South. John Lewis and other civil rights marchers face Alabama state troopers on Bloody Sunday in 1965 Selma. Gov. George Wallace blocks the doorway at the University of Alabama in 1963 to prevent blacks from enrolling. Freedom Riders sit nervously on a bus just days before it was firebombed.

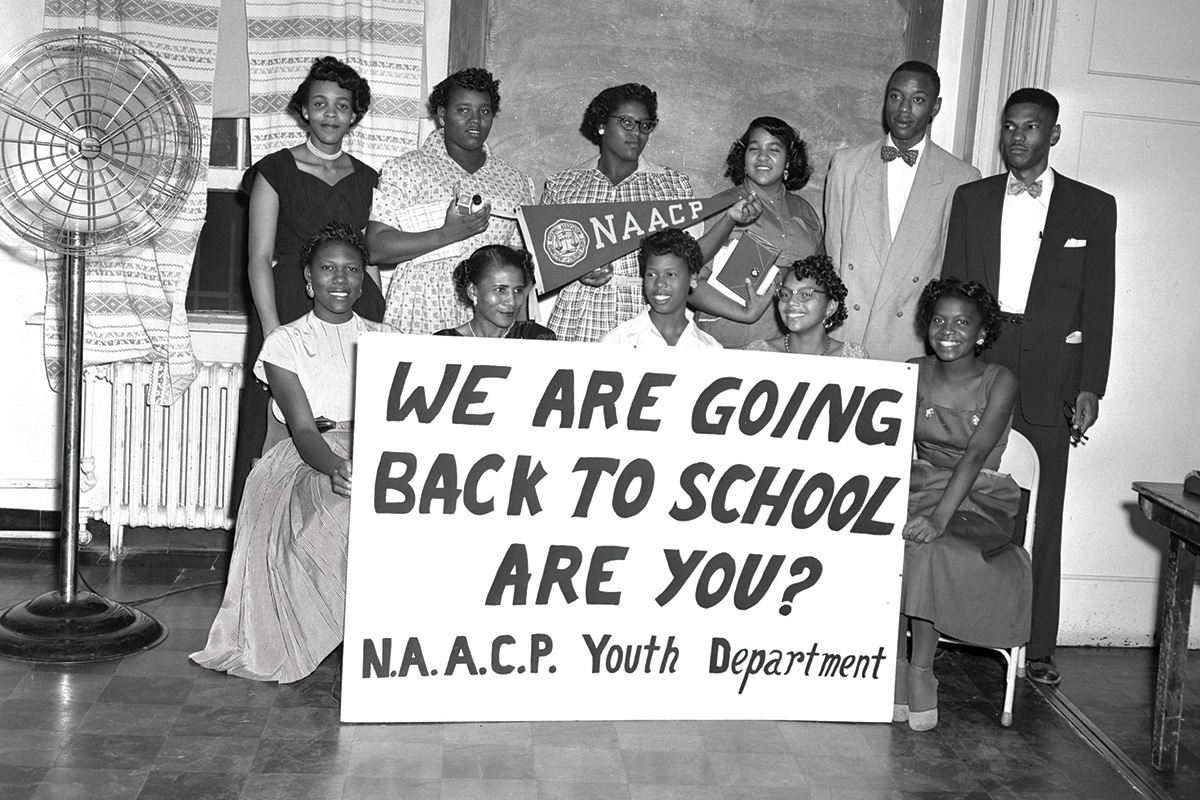

The struggle in Texas is represented extensively by the work of Dallas-Fort Worth-area photographers R.C. Hickman and Calvin Littlejohn. Hickman documented racial inequality in North Texas for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. His photograph of a 1950 classroom offers a stark reminder that educational facilities under the “separate but equal” doctrine were anything but equal before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education began the long process of desegregation in public schools. Like other photojournalists, Hickman risked his own safety to document racial inequalities and the violence that accompanied integration efforts.

A Littlejohn photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. and others at Dallas’ Love Field in 1959 is one of many in the exhibition that underscore Carleton’s observation that “Historic images can be read like diaries or letters. They’re chock full of information.” The ladies wear hats and gloves, and one of the men sports an Open Road Stetson. King’s expression is beatific.

A 1957 image by Dallas photojournalist Shel Hershorn shows the result of integration as black and white students work on a project together in a Pleasanton school.

The cover of a souvenir program for the 45th Annual NAACP Convention, held in Dallas in 1954, features a cowboy cutting a barbed wire fence. The program and several other items are from the center’s Juanita Craft Collection. A longtime civil rights organizer and activist, Craft’s home is now a museum maintained by the city of Dallas.

Other examples of strife in Texas involve higher education. There’s the case of Heman Sweatt, who fought to enroll in 1946 as the first black student in the University of Texas School of Law. And there’s Barbara Smith Conrad, a future mezzo-soprano opera star who was to appear on a university stage in Dido and Aeneas with a white co-star in 1957; pressure from the Legislature and alumni led to her removal from the performance. A telegram of protest comments, “This Jim Crow action indicates a horse and buggy Texas.” The center produced the 2011 film on the controversy, When I Rise.

A notice posted at the entryway of Struggle for Justice advises that some of the exhibition’s contents might be difficult for visitors to experience. The powerful images produce strong emotions. “During one tour of the exhibit, a man in his 30s burst into tears,” says Ben Wright, Briscoe’s associate director for communications. “He said, ‘I wish my dad could be here to see this. He lived through it.’ ”

Writer Gene Fowler specializes in Texas history.