Trees have been a valuable resource since the beginning of mankind. During our earliest days, trees provided shelter, and cast-off limbs were fashioned into crude tools for protection. As our skills, knowledge and craftsmanship progressed, so did our uses for wood. A tree limb became a club, a spear, and then a bow and arrow. Sticks, rubbed together, created fire for warmth and cooking.

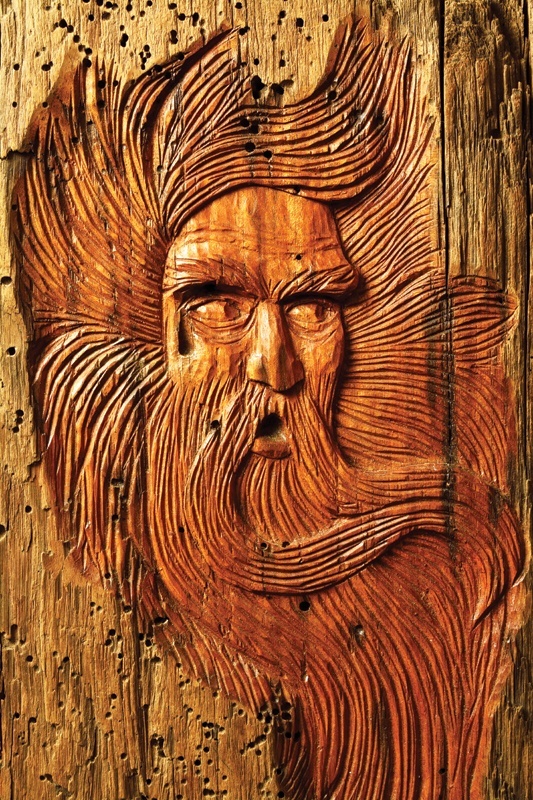

At some point, man noticed that wood itself was a thing of beauty, marked with lines and patterns that capture the imagination. Taking a sharp piece of bone or stone, he began to carefully whittle the wood, creating the shapes and features of animals, objects and people around him. Thus, the art of woodcarving came to life.

Today, the love of working with wood often begins as a youthful passion. Other times, the fascination with shaping wood into art and useful objects lights a fire in one’s soul later in life.

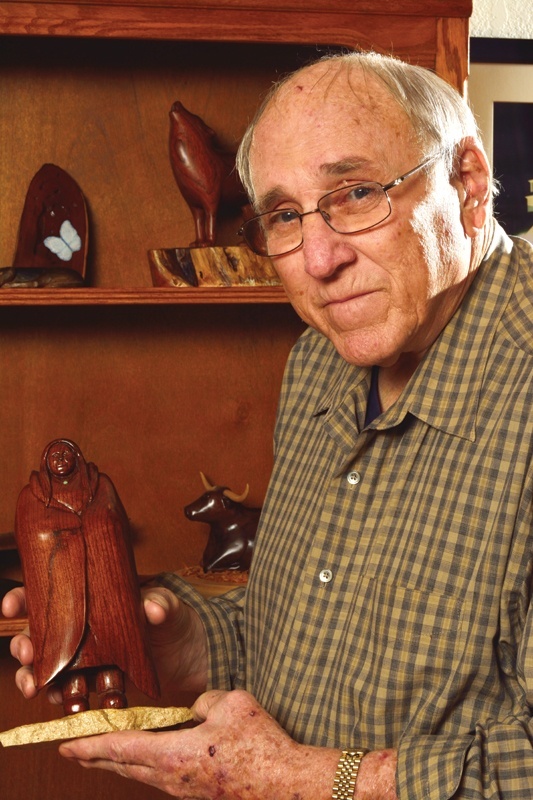

“I began carving in the 1960s when a good friend of mine showed me a woodcarving he had done,” says John Fletcher of Jasper. “I decided to give it a try myself, and soon it became a part of my life. Here I am today, at age 78, still finding pleasure in working with wood.”

Fletcher does a little bit of everything in his woodworking, including relief carving, the art of crafting figures into a flat piece of wood.

“I just create whatever crosses my mind as I look at a piece of wood,” he says. “I mainly carve horses, eagles, free-form birds and butterflies.”

Sometimes Fletcher sees the subject in the piece of wood before he even begins to carve. But other times, he will see a carving crafted for a gallery or look at a photograph and decide that he’d like to emulate that design. Depending on the subject or design, he may do several carvings in a row of the same subject.

Fletcher most enjoys working with four specific types of wood. His favorite is mesquite, found predominantly in Central and South Texas. He also likes basswood, butternut and walnut.

“I prefer softer woods because they are easier to carve,” he says. “However, harder woods like walnut have a beautiful grain and are easier to finish.”

Fletcher’s work is on display at RS Hanna Gallery in Fredericksburg and at the East Texas Art League in Jasper.

“The message I try to send through my carving is that I enjoy doing it,” he says. “I hope that anybody who looks at a piece and likes it well enough to spend their own money on it will enjoy it also.”

East Texas is home to another wood artisan, Mike Beumel, who lives in the small town of Moscow, just north of Livingston, and also happens to be a utility designer for Sam Houston Electric Cooperative.

“Through the years, I’ve built 70 or 80 rocking chairs from scratch, including several for women expecting to be new mommas,” Beumel says. “But I also refinish antique wooden furniture that folks bring to me, including replacing worn or damaged seats with woven cane.”

Beumel also finds old pieces in resale and antique shops and brings them back to life. One rocking chair he found was so dirty and ugly that he didn’t know what he had until he tightened it and cleaned it up. It had unique carvings and quickly became one of his favorite pieces.

“It’s one of those things that hardly anyone does anymore,” he says. “It’s more a labor of love than something you would do to make a lot of money.”

He’s also refinished a lot of rustic pieces belonging to people who want to have something reminiscent of the time in which the piece was made.

“I enjoy the satisfaction of taking something that didn’t look like much and making it match the period it came from, while not taking away the character of the wood,” he says. “I don’t want it to look new, because anybody can have something new. I like to remain faithful to what it is.”

Beumel has worked with a wide variety of woods, especially for his furniture restoration projects.

“One rocker I refurbished had been sitting for many years on a front porch,” he says. “It was made of red gum, a type of wood you just don’t see anymore. It had a beautiful reddish-brown-green color. I wove the chair seat but only put a light sanding on the wood, and it turned out absolutely beautiful.”

He even works with raw wood on a lathe, another type of woodwork called wood turning.

“When you turn ash, the wood grain looks different one way than it does when you move it another way,” he says. “Refinishing the wood so that the colors look even is a challenge that takes time to learn.”

Beumel believes all types of wood have their place in art and utility pieces.

“A lot of the softer woods take stains more evenly, but you don’t have as much color shift in the grain,” he says. “Even the climate where the tree was grown affects the wood grain and the color. Over time, you start to notice the idiosyncrasies and distinctiveness of each species of wood.”

Beumel likes folks to use the woodwork he’s made or restored for them.

“I hope that people will see what they’ve gotten from me as a picture of the past—a piece of craftsmanship they’re going to cherish,” he says.

His home is filled with wood items he has crafted or refinished, but there are several pieces in his personal collection he will not sell. He remembers a piece with intricate weaving he made years ago that he now regrets selling. Beumel knows he can’t keep them all, and he takes comfort in knowing his pieces will be appreciated.

“When I make rockers for new mothers, I want their kids to have memories of that rocker and say to themselves, years from now, ‘Mom used to rock me in this chair,’ ” he says.

Another East Texas woodworker is Ray Epps of Livingston. Epps was raised in Texas but lived in Australia for 18 years and has traveled much of the world.

“I began working with wood when I was 5 years old,” Epps says. “I made bookcases, tables and bookends. But a real turning point came when I went to a show in Australia and saw someone using a wood lathe. I went right out and bought a lathe and have been using one ever since.”

Epps makes wooden ballpoint pens, salt and pepper mills, cutting boards and all types of bowls. Some of his bowls are made from a solid piece of wood, while others are constructed of different species of wood cut into wedges, glued into a ring and then made smooth with a lathe.

“By using different species of wood, you can end up with unique and unusual designs,” Epps says. “I also make jewelry boxes, which are usually made from several layers of wood laminated together. Sometimes I use different species of wood in one box to create contrasting colors and make the box stand out even more.”

Epps uses all types of wood, both domestic and foreign. Walnut is one of his favorites, as are oak and mahogany. African bubinga, melaleuca and jarrah from Australia are favorites as well.

“I like to take a piece of wood and show the beauty of it through the grain and the natural patterns within it,” he says. “If there are defects in the wood, it doesn’t bother me. I try to make the defect a feature of the object itself. I’m not trying to make it look like it was factory produced. I want every piece to be unique.”

Epps is always open to new ideas for his work. If his customers have a piece of wood they want to get rid of, he usually makes something out of it for them, as a thank-you for donating the wood.

“We sell to people all over the world,” he says. “I have a passion for working with wood and hope that people who like my work will know that I do it because I enjoy it.”