SUVs, pickups and 18-wheelers rumble along state Highway 21, the historic route known as El Camino Real, which means “the royal highway.” Heading east, they leave the Davy Crockett National Forest at the Neches River and make the gradual climb out of the river valley. The landscape flattens into a plain about a mile east of the river, where drivers pass a mysterious high grassy mound flanked by a historical marker. They pass two more mounds and a curious beehive-shaped house made of thatch.

Most traffic continues 6 miles more to Alto in Cherokee County. But for those passers-by who stop for an hour or more, the 397-acre Caddo Mounds State Historic Site reveals the fascinating story of the most advanced prehistoric culture in Texas—and the one that gave the state its name.

A stroll through the site’s visitors center, then along a short trail to the mounds, takes you on a walk back in time. As part of the Texas Historical Commission, the site shows how a group of Caddo created a complex culture that dominated this part of East Texas for more than 500 years.

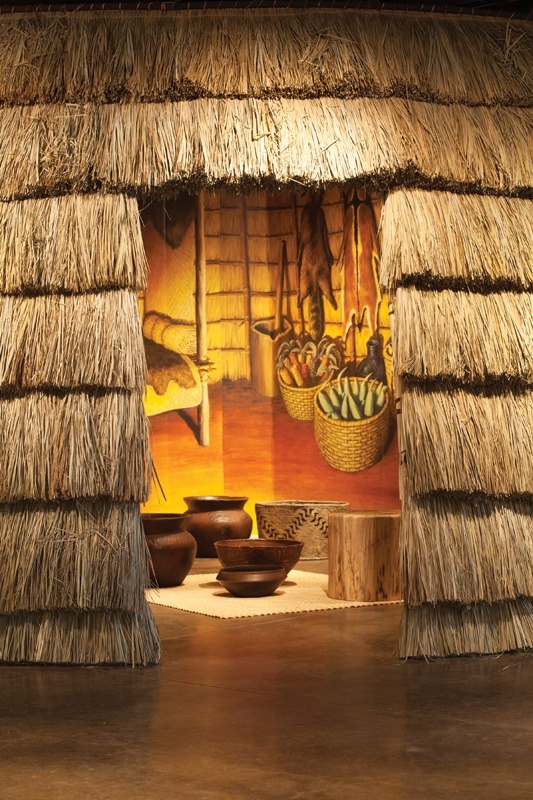

The museum offers a short video on Caddo history plus hands-on exhibits in and around a mocked-up grass house. Displays showcase replicas of artifacts found at the site during archeological digs that took place around 1940 and again around 1970. Artist renditions and narrative panels reflect these archeological findings and more recent, noninvasive magnetometer studies. Together, the research reveals what archaeologists believe the village and its three mounds looked like during its active period, roughly 750–1300 A.D.

Generations of Caddo Indians lived here as farmers, hunters and gatherers. The Hasinai Caddo found this alluvial site perfect for their home. The rich soil proved fertile for their favorite crops: corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, amaranth (a grain) and sunflowers. Area forests offered deer, turkeys and squirrels that the Caddo hunted with their characteristic bows and arrows crafted from the Osage orange tree. A natural spring made fetching water easy, and the nearby Neches River added catfish and bass to their diet. Just to the west, open prairies even invited occasional bison hunts.

During the growing season, the village remained a beehive of activity as villagers tended cornfields. Preserved vegetable and meat harvests filled drying racks and storage platforms made of saplings and thatch. Villagers used cane and native grasses to weave carrying baskets. Others dug river clay and formed it into signature Caddo pottery.

The festival in April includes dancing and storytelling of the Hasinai band of the Caddo Confederation of Binger, Oklahoma, whose ancestors were part of the mound culture.

Ceramic storage vessels and cooking pots were fairly plain. But finely crafted ceremonial vessels, smoking pipes, effigies and ornaments boasted complex circular and rectangular designs unique to Caddo artisans. The style was so distinct that 20th-century archaeologists could identify Caddo sites from the pottery shards they found.

Mighty Mounds

Caddo groups endured for many centuries across northeastern Texas, southeastern Oklahoma, southwestern Arkansas and northwestern Louisiana. At the height of their influence (around 1100 A.D.), the Caddo village on the Neches served as the greater region’s southwesternmost ceremonial, spiritual and political center Digs and magnetometer readings have shown that this village supported around 900 people living in 150 or so round grass houses that measured up to 45 feet in diameter. Elite tribal leaders developed sophisticated trade and political systems to unite the Caddo people scattered along the Neches and Angelina river valleys, according to Anthony Souther, site manager.

These elites lived and ruled from temples and houses built on the largest of the site’s three mounds, which once reached 35 feet high. Villagers constructed the temple mounds over many years by hauling dirt in large woven baskets from nearby borrow pits. Leaders conducted ceremonies from atop the second, lower platform mound. The third mound, which measured 20 feet tall and 90 feet in diameter, contained the buried remains of some 90 people. The burial mound probably was reserved for elites and their families and servants. They were buried along with finely crafted objects meant to accompany them on their afterlife journey.

Education director Rachel Galan gives a tour of the ancient burial mound to a school group.

Archaeological excavations found that some buried materials—such as stones for arrow points and shells and copper for jewelry—came from as far away as the Great Lakes and Florida. The finding verifies the Caddo’s significant role as traders in a vast Native American network. Caddo trade routes were so extensive that the earliest Spanish colonialists used them in the late 1600s to establish military posts and missions along what they called El Camino Real de los Tejas (“the royal road of the Tejas”). By that time, the village and ceremonial center on the Neches had been long abandoned, but Caddo groups continued to live in the area.

They greeted the European newcomers with their word for friend or ally, “taysha.” The Spanish recorded the word as “Tejas,” a name that eventually became Texas.

You can walk a short segment of the original El Camino (now a designated national historic trail) along an interpreted trail at Caddo Mounds State Historic Site.

Living Legacy

To boost the visitor experience, Caddo Mounds State Historic Site has added several new attractions over the past five years. In 2014, the site opened an improved visitors center and museum. Two years later, the Caddo grass house was built on-site with the assistance of current Caddo tribal members—bringing traditional Caddo culture to life.

The Caddo Mounds State Historic Site’s museum interprets the life and times of the Hasinai Caddo Indians.

Last year, the ground itself became part of the historical retelling of the Caddo story. Some 40 acres of native prairie are being nurtured adjacent to the temple mound. Near the visitors center, the Snake-Woman’s Garden features 2,500 square feet of growing space for edible plants from the Caddo diet, then and now. The garden’s name comes from a Caddo oral story about the Snake-Woman who distributed the seeds of all living plants but warned the people to take care of the plants or else a poisonous snake would bite them.

“Snake-Woman’s Garden gives us a place to focus on the Caddo people as farmers and talk about the crops they cultivated from prehistoric plant domestication to modern cooking gardens,” explains Rachel Galan, site educator and interpreter. “Besides, the garden is beautiful, especially when the sunflowers are blooming.”

Site manager Tony Souther demonstrates the atlatl, an ancient hunting weapon.

It remains unclear why the Caddo abandoned this site around 1300 A.D., but they probably did so on purpose, based on interpretations of the final layers of clay they added to cap the mounds. Hasinai Caddo continued to live in East Texas until the 1830s, when pressure and disease brought by immigrating American pioneers threatened their existence. Caddo groups moved voluntarily to the Brazos River to avoid Anglo-American colonization. The U.S. government forced them to the Brazos Indian Reservation in 1855, and then in 1859, sent the thousand or so remaining Caddo to the Washita River in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma.

Today’s Caddo Nation remains a federally recognized tribe headquartered near Binger, Oklahoma. Caddo Mounds State Historic Site remains a sacred place for Caddo, who continue to work with historians to keep alive their traditions.

“In recent years we have worked hard to develop a long-term relationship with the Caddo Nation to make this a welcoming place for them, so they will feel at home here again,” explains Souther. “To do justice to the historic interpretation of this special place, we must involve the Caddo people themselves.”