During much of the 19th century in the eastern half of Texas, steamboats and barges floated people, their goods and products along the region’s major rivers—the Sabine, Neches, San Jacinto, Trinity and Brazos—to coastal markets, especially Galveston.

The westward movement of American settlers and traders required the services of ferryboats. At first they were little more than small wooden rafts attached to a sturdy rope or cable anchored on both banks. Strong ferrymen pulled on the cable by hand to move the raft across a waterway, sometimes with the help of a long pole.

Dozens of ferries sprang up on eastern rivers to transport passengers, animals, wagons and other cargo. Stagecoach and mail routes began carrying passengers and mail from one community to another via the ferry crossings. It was well into the 20th century that the demands of an industrial nation—heavier cargoes and tighter schedules—pushed almost all ferries off the transportation map. Steel railway and highway bridges became the way across.

San Jacinto River

One of the state’s first ferries is also one of the nation’s oldest ferries still in operation. Early settler Nathaniel Lynch moved from Missouri to Mexican Texas as a colonist of Stephen F. Austin’s Old Three Hundred. In 1822 he began operating a ferry on the San Jacinto River near its confluence with Buffalo Bayou in today’s Harris County. Lynch’s Ferry sat on an old Spanish coastal road traveled in 1836 by Mexican troops pursuing Gen. Sam Houston during the Texas Revolution.

For three tense days, the ferry carried 5,000 fearful locals eastward across the river as they fled the advancing Mexican army, an episode known as the Runaway Scrape. Once the families crossed safely, the Lynches moved their ferryboats to prevent Mexican troops from crossing. That’s where the Battle of San Jacinto took place.

Passengers on the Lynchburg Ferry get a view of the San Jacinto Battleground Monument.

Randy Mallory

A 567-foot monument now marks the site where Houston defeated Mexican Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna. In the shadow of the star-topped monument, a modern conveyance, the Lynchburg Ferry, still does its job. Operating weekdays

4:30 a.m.–8 p.m., two 85-ton diesel ferryboats carry up to 10 vehicles per trip of mostly commuters. Harris County took over management of the ferry in 1888 and continues to offer the service free of charge for the five- to 10-minute ride across a half-mile stretch of the Houston Ship Channel. Overlooking the scene, Juan Seguín Historic Park offers information panels to honor ferryboat history.

Two East Texas ferries operated by the state also have deep roots. The Texas Department of Transportation operates free coastal ferries carrying 8 million passengers annually as an extension of its highway system. In 1929 a private ferry began service between Galveston Island and Port Bolivar Peninsula. The state took over operations the next year, and it still runs day and night, connecting land segments of Highway 87. Each diesel-electric ferryboat carries up to 70 vehicles per trip across nearly 3 miles of Galveston Bay in about 18 minutes.

Since the 1930s a public ferry has carried passengers and vehicles between Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula.

Randy Mallory

Another free state ferry crosses Corpus Christi Ship Channel as part of Highway 361 between Aransas Pass on the mainland and Port Aransas on Mustang Island. The 20-car ferry travels a quarter-mile route in less than 10 minutes. The ferry began as a private enterprise in 1911 and was later taken over by Nueces County. TxDOT took over operation of the ferry in 1968.

Sabine River

Some 200 years ago, the Old San Antonio Road through Nacogdoches served as the most important commercial and immigration route across Texas. By 1800 a ferry was operating at the road’s Sabine River crossing near Milam in today’s Sabine County.

Prominent settler James Gaines bought the ferry in 1819 and operated it for 33 years. American immigrants arrived from Louisiana in such numbers that nearby Pendleton served as a Republic of Texas port of entry where officials collected customs duties.

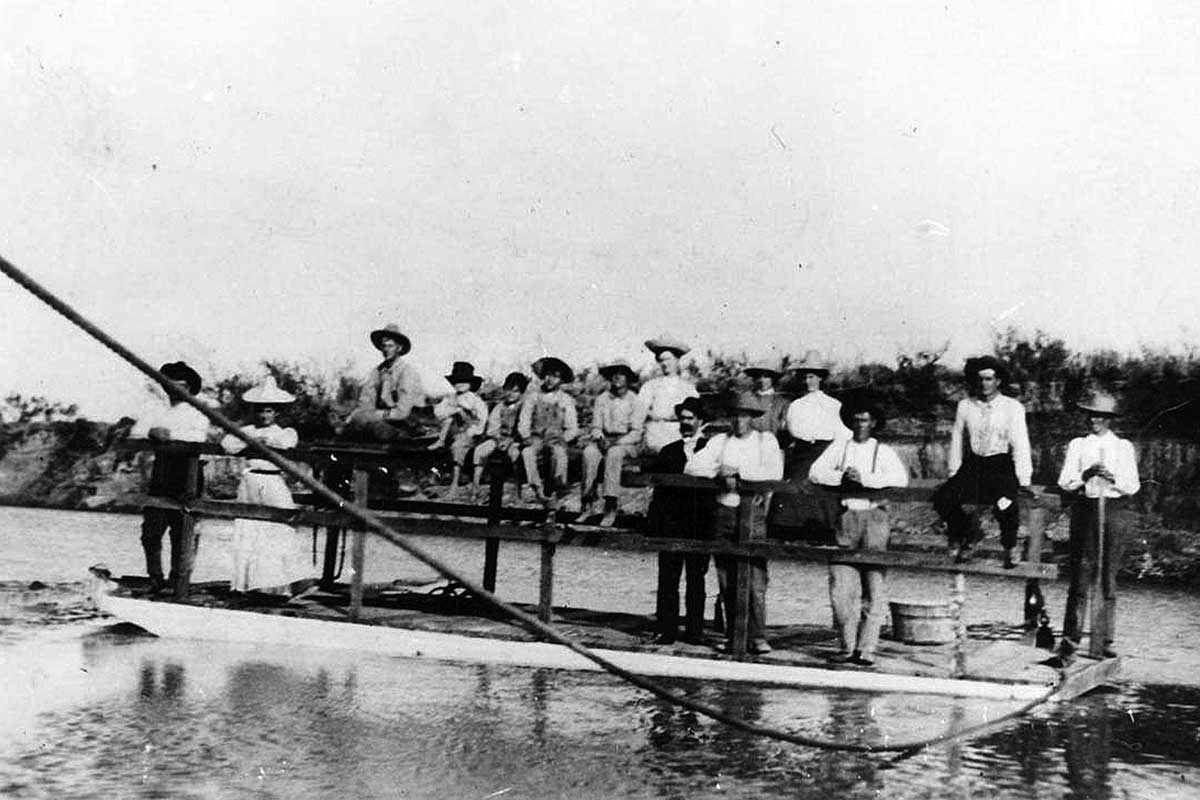

The Pecos River crossing between Porterville and Arno in 1907.

Permian Basin Petroleum Museum

The ferry operated until 1937, when the Gaines-Pendleton Bridge rose above the river to connect Texas Highway 21 with Louisiana 6. Toledo Bend Reservoir submerged the old ferry site, but on a hill above the water sits the Gaines-Oliphint House, the state’s oldest standing log structure, owned by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. Built around 1815, the house provided lodging for notables such as Sam Houston, Davy Crockett and Stephen F. Austin as they rode the ferry into Texas.

Neches River

In the early days of the Republic of Texas, ferries were a vital part of frontier infrastructure. Local authorities regulated them to ensure the traveling public had safe passage at reasonable rates. Ferryboat fees—in the early decades typically no more than $1–$2 for light to heavy wagons, 25 cents if on horseback and half that for someone on foot, and 4–6 cents per cow and less for smaller animals—had to be posted on-site. Crossings at night and in rough weather might cost more. There may have been an extra charge of a penny per head for swimming across loose cattle, horses, hogs or sheep if the ferryboat assisted.

Operators also had to slope and maintain riverbanks to allow wagons, carts and later automobiles and trucks to drive safely from the top of the bank down onto a ramp secured to the end of the ferryboat.

Bonner’s Ferry over the Trinity River, Anderson County.

Palestine Public Library

In her book Reflections on the Neches, Big Thicket naturalist and author Geraldine Watson describes a Neches River crossing at the Sheffield Ferry, between Spurger and Kirbyville. “When the river ran fast,” she wrote, “it took nerves of steel to negotiate a horse-drawn wagon or even a motorized vehicle aboard.”

Ferry workers could do the job if a driver was nervous. Still, accidents happened. A truck carrying caged chickens once landed in the water when the driver accidentally hit the accelerator. Another time, a mule couldn’t hold back its heavy wagonload, which rolled uncontrolled into the Neches.

Darrell Sheffield of Silsbee heard countless ferryboat stories as a youngster sitting at the knee of his great-grandmother, Suzie Jones Sheffield. Her father-in-law, Robert Wynn Sheffield, joined other family members in running the Sheffield Ferry, at today’s FM 1013 bridge, in the mid-1800s. More than one ferry story involves ferrymen unknowingly carrying bank robbers across. As the only reliable way to cross the Neches, the ferryboat carried everyone—good and bad.

According to Watson, the Sheffields sold the ferry, and by 1917 it was owned and operated by the Jenkins family. One of the Jenkins clan, a stout fellow named Fred, was ferryman the day that noted Houston Chronicle columnist Leon Hale took a ride just before the ferry closed.

“Jenkins had a wooden tool, about the size of a baseball bat, slotted at one end. He’d fit the slot onto the [ferry] cable, haul back on it, and the boat would move a foot or two,” Hale wrote. “Several dozen such strokes were necessary to get the boat across. The power that moved that heavy 40-foot boat across the river came from Jenkins’ strong back.”

J.W. Ryon at a ferry crossing in Richmond in the 1890s.

Fort Bend Museum

The Sheffield Ferry was the last public ferry on the Neches until a bridge replaced it in 1959. In 1991 drought conditions lowered the Neches water level such that it revealed a sunken ferryboat. An investigation by the Big Thicket National Preserve, which borders the wreck site, identified it as a nearly intact early 19th-century ferryboat. They couldn’t tell which of many upstream crossings it had served.

The wreck site is about a mile downstream from today’s Sheffield Ferry Boat Ramp, operated by Ron and Margie Reeves Bingham, who launch fishing boats, offer canoe trips and rent RV spaces. The couple grew up on the river and have property on both sides—served by Jasper-Newton Electric Cooperative in Jasper County and Sam Houston Electric Cooperative in Tyler County.

“Folks around here still take a lot of pride in their history, including the old ferries along the Neches,” Margie Reeves said, adding that a river camp house built by her father boasts a porch held up by posts from the sunken ferry.

A wooden ferry loaded with cattle crosses the Brazos River.

Fort Bend Museum

Stories about hand-pulled ferries are part of Texas history, but you can see at least one still in operation today: The Los Ebanos Ferry is a hand-operated cable ferry that crosses the U.S.-Mexico border between Los Ebanos, Texas, and Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, Tamaulipas, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday–Friday.

Since 1950 ferry workers at this crossing have pulled on a cable stretched across the narrow Rio Grande to carry three cars at a time and pedestrians. Like its 19th-century predecessors, the ferry provides residents of nearby towns convenient, safe transit across the river. As an official port of entry, Los Ebanos Ferry has a U.S. Customs and Border Protection station that inspects passengers and vehicles entering the U.S.

Resting in the shade of the namesake ebony tree that anchors the ferry’s cable, a state historical marker proclaims this throwback to frontier times as the only government-licensed hand-pulled ferry on any U.S. boundary.