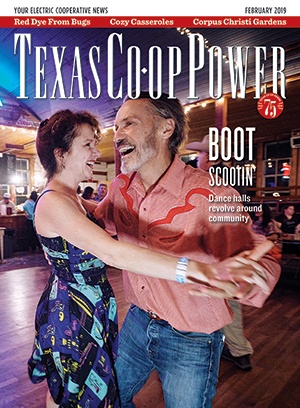

Imagine this scene in a Texas dance hall:

A band belts out a tune while couples of all ages spin one another around a hardwood floor. Some steal kisses or show off fancy twirls. A little girl, balanced atop her granddaddy’s boots, sways in time. Kids knee-high to a grasshopper race around the floor, and no one fusses. At rustic tables, friends and families chat, sip drinks and wave at dancers gliding past. A short reach away, babies and toddlers snooze on blankets spread across the floor.

The folksy scene could describe a dance hosted last month at Anhalt Hall in Spring Branch or one held in the 1890s at Braun Hall in northwest San Antonio.

Dancers can two-step and twirl all evening the first Saturday of every month at Twin Sisters Dance Hall near Blanco.

Dave Shafer

“Dance halls are magical because their culture hasn’t changed since the 1870s, when the first ones were built,” says Patrick Sparks, a structural engineer and historic preservationist based in San Antonio. “Dancing’s as fundamental to Texas as the Alamo, cowboys, longhorns and oil.”

More than 1,000 dance halls built by German, Czech, Polish and a few Swiss immigrants once dotted parts of Texas. In the mid-19th century, the weary newcomers stepped off ships in Texas ports, most often Galveston or Indianola, on their way to settle as far west as the Hill Country.

Living conditions were harsh, and yet these isolated settlers worked hard to establish their unique way of life. To provide their friends and neighbors a place to meet, discuss business, share barbecue dinners and dance, they constructed spacious halls. Each building incorporated the skills of its artisan community, reflecting its customs and musical tastes. Architecture varied from simple, metal-sided barns with window flaps, such as those of Kendalia Halle, to round halls with a center support column, such as Bellville Turnverein Pavilion.

As meeting places, the buildings served the primary interests of their founders. Progress (fortschritt) and shooting club (schützen verein) members built the whitewashed Nordheim Shooting Club Dance Hall. German businessmen built an ornate dancing pavilion called the Garten Verein (garden club) for Galveston’s German community. Near Burton, one of many German gymnastic clubs (turn vereins) built the La Bahia Turn Verein Hall. A German singing society (gesangverein) founded the Millheim Harmonic Harmonie Verein Hall in Sealy.

In Czech communities, polka dancers kept floors hopping at halls built by two fraternal orders: the SPJST (Fayetteville’s SPJST Hall No. 1) and KJT (Ammannsville’s KJT Hall). Most of the other halls were built by religious or agricultural organizations, and individuals built a few. One example is Sefcik Hall in Seaton, a two-story clapboard building built in 1923 by Tom Sefcik. His daughter Alice Sefcik Sulak, now in her 80s, still oversees Sunday night dances on the second floor.

Each distinct, the buildings had one common feature: an expansive wooden floor that welcomed families. “Then and now, that’s what makes a true Texas dance hall,” says Deb Fleming, executive director of Texas Dance Hall Preservation in Austin. “Its largest architectural feature must be the dance floor, and it must also allow children, unlike a saloon or honky tonk.”

Fleming, a San Antonio native who did not grow up around Texas dance halls, discovered her ancestral roots because of one. In 2007, she visited Panna Maria, considered the nation’s oldest Polish settlement, established in 1854, to research the community’s historic hall. At the visitors center, a local woman with a laptop offered to print out Fleming’s genealogy. Her family tree traced back to Johann Rzeppa, Flemings’ great-great-grandfather and one of Panna Maria’s original settlers.

“I had no idea about our family’s connection to Panna Maria,” says Fleming, a Guadalupe Valley Electric Cooperative member. “Neither did my father. The experience made me wonder how many other Texans have their own family connection to a Texas dance hall and don’t even know it.”

Thanks to dance halls, Texas music is known worldwide. Without them, those early brass, string and accordion bands wouldn’t have birthed such genres as western swing, country or conjunto. Eventually, several bands made a good living, traveling from one dance hall to the next. Bob Wills, Willie Nelson, Hank Williams and Ray Benson are among those who got their starts in dance halls.

Fewer than 400 halls survive in Texas. Of those, about 25 percent stand abandoned, such as Gillespie County’s Cherry Springs Dance Hall, where Elvis Presley, Nat King Cole and Patsy Cline performed. Or they’re used for storage.

In 2008, Preservation Texas collectively identified all Texas dance halls as endangered places worthy of protection as architectural, historical and cultural landmarks. The nonprofit advocacy group cited neglect, suburban development, highway projects, shrinking grassroots support and lack of public awareness as threats to dance hall survival.

A dancer who came all the way from California on a dance hall tour looks over photos at Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall.

Dave Shafer

The designation came a year after Sparks, along with historic preservationist Stephanie McDougal and the late Texas music historian Steve Dean, founded the nonprofit Texas Dance Hall Preservation. Since its start, the volunteer group has worked to inventory existing halls, spread the word about their historical importance and partner with owners to keep them afloat.

Dean’s advocacy for dance halls ran deep. In 2014, he asked via social media whether someone could make a documentary about them. Filmmaker Erik McCowan of Rosanky responded.

“First we visited the Round Top Schützen Verein’s annual shooting competition that’s been held every year since 1873,” recalls McCowan, a Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative member. “That’s when I realized the history of these places runs much deeper than I thought. After Steve and I saw what was left of New Bern Helvetia Hall near Taylor, I knew I had to make a film.”

More than three years in the making, Dance Hall Days shares the down-home stories of 56 classic halls. Some stand forgotten, such as Cistern Hall in Cistern and Kreutzberg Shooting Club Hall near Boerne. Fire destroyed several, including the Fredericksburg Social Turn Verein Hall in 2016 (members voted to rebuild). Siblings restored their family’s Park Hall (now called Hruska’s at Park) near Fayetteville, and Renck Hall in Warrenton hosts antique sales. But dancing still ranks No. 1 at many others, including the Albert Dance Hall in Albert and Schroeder Hall in Goliad.

Throughout the 82-minute film, Dean steps in and out of halls, sharing his hopes and wisdom. Sadly, he died April 28, 2018, the day after Dance Hall Days won Best Texas Film at the Hill Country Film Festival in Fredericksburg.

Rich stories captured by McCowan’s film abound within the walls of Texas dance halls. “These places live and breathe the stories of Texas,” Fleming says. “They’re melting pots of our state’s culture. Every time we lose one, we lose a piece of Texas history.”

Web Extra: A Twin Sisters Dance Hall fixture in his familiar position behind the bar, also keeps an eye on the dancers and makes sure there is ample cornmeal on the floor to keep the boots scootin’.

Dave Shafer

Twin Sisters Dance Hall

Blanco | Served by Pedernales EC

Fewer than a dozen couples two-stepped across the hardwood floor one summer night in 2015. Jo Nell Haas, watching from her perch by an open door, thought back to monthly dances when crowds jammed the checkerboard tin-sided Twin Sisters Dance Hall.

German immigrant and rancher Max Krueger built the hall, 7 miles south of Blanco, as a dance pavilion and community center in the mid-1870s. Severe drought later forced Krueger to sell the building. Subsequent owner Henry Bruemmer Jr. sold the hall and surrounding land in 1918 for $5 to Twin Sisters Hall Club, a nonprofit group that still runs the facility.

Through the years, countless families have gathered at Twin Sisters, once the site of a German community named for a pair of nearby hills. In the 1970s, Haas met her husband, Joe, on the oak floor. Like many other couples, they taught their children how to dance there, and their families celebrated weddings beneath its arched blue ceiling.

Recent attendance at dances, however, had waned to the point where Haas, club president, considered closing the doors. She knew the night’s ticket sales would barely pay the band. Frustrated, Haas slipped outside that night in 2015 and tapped a familiar number into her cellphone.

On the other end, Steve Dean picked up. He listened as Haas unloaded her worries. Then his passion for historic halls took hold. “Keep your head up,” he yelled. “Don’t give up! I’ll rob a bank if I have to, to keep Twin Sisters open. But don’t you shut those doors!”

Three summers later, Haas reflects back on that night. “I thought we’d have to shut down,” she says, seated at one of Twin Sisters’ wooden tables. “But then the TDHP showed us how to up our marketing and book bands that are more popular.”

Nowadays, big crowds turn out for Twin Sisters’ monthly first Saturday dances. Hall rentals for weddings, proms, parties and reunions have boosted revenues. In March 2018, the club replaced Twin Sisters’ leaky metal roof with money from fundraisers and grants, including a community grant awarded by Pedernales EC.

“Twin Sisters Dance Hall has always been about family and community,” Haas says. “All of us volunteers work hard to continue that tradition.”

Twin Sisters Dance Hall, 6720 Highway 281 S., Blanco, 78606; (830) 833-5773; [email protected]; twinsistersdancehall.com.

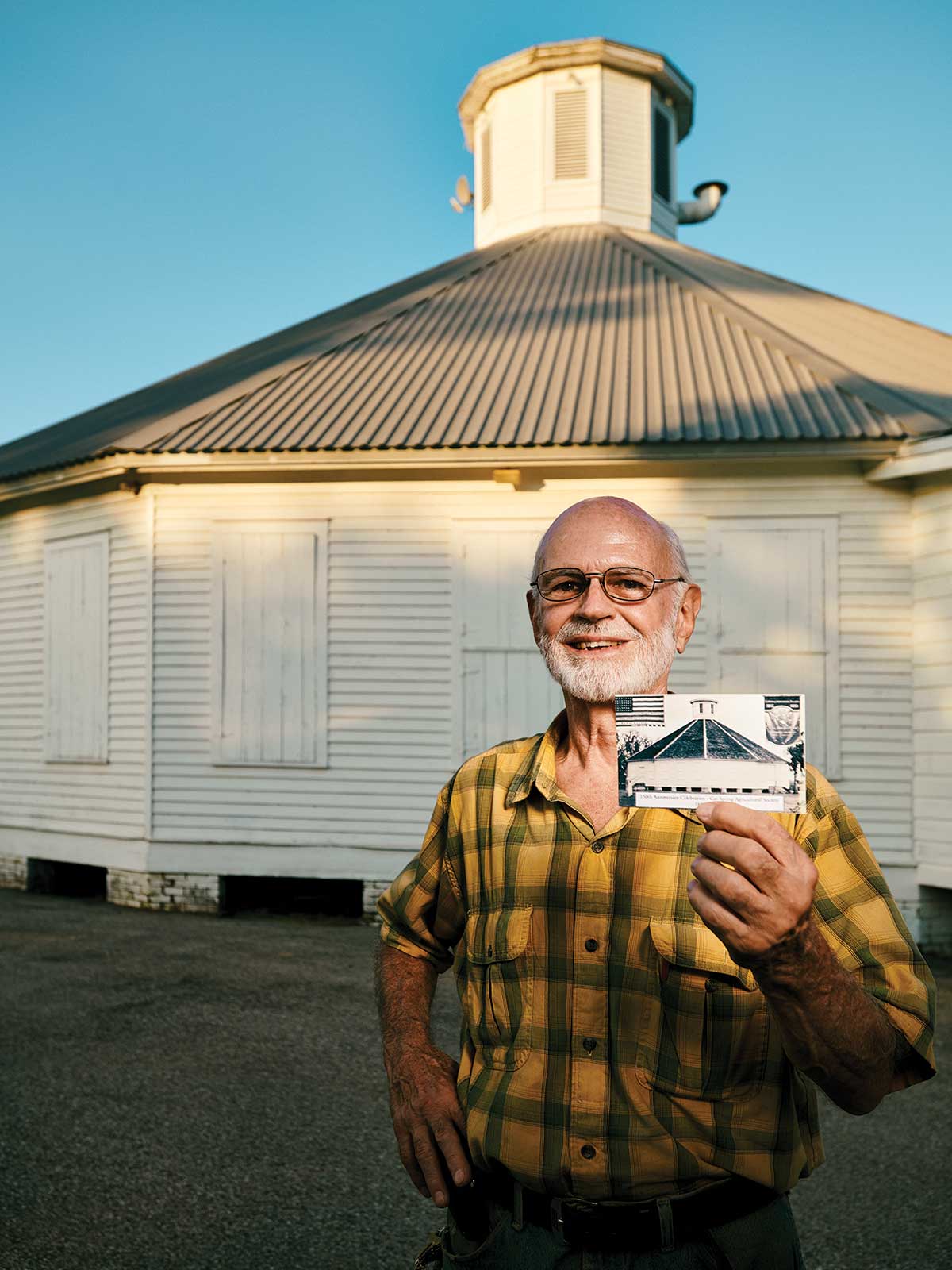

David Wade holds a 1956 postcard from Cat Spring Agricultural Society’s 100th anniversary.

Dave Shafer

Cat Spring Agricultural Society Hall

Cat Spring | Served by San Bernard EC

Many of the German and Czech immigrants who settled Cat Spring in the 1850s had education but no farming know-how. They joined together in 1856 as the Agricultural Society of Austin County, later renamed for Cat Spring. The men met regularly to trade information and acquire garden seeds. They and their families tended fruit orchards, canned vegetables, compared fences and experimented with growing tea and coffee.

“We were the first extension service before Texas A&M University,” says David Wade, Cat Spring Agricultural Society treasurer and a San Bernard EC member. “The U.S. Patent Office would send seeds to the society for testing, and members reported back on how they performed.”

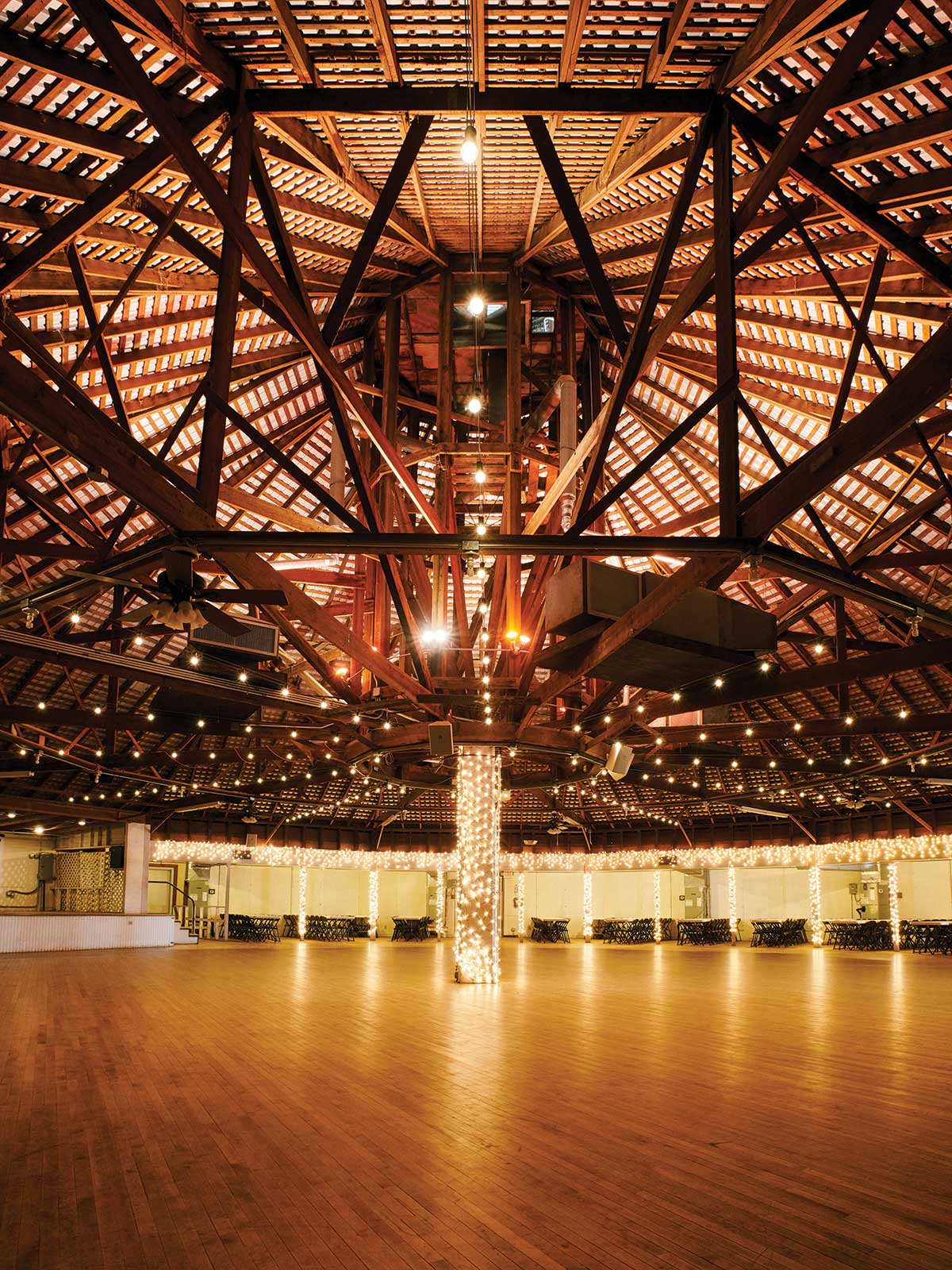

In 1902, German carpenter Joachim Hintz built the group’s 12-sided, white-clapboard social center, the largest of the three round halls he built in Austin County, including the Bellville Turnverein Pavilion and Peters-Hacienda Community Hall in Sealy. During dances, couples proceed counterclockwise on the pine floor around the center pole, which supports the beamed ceiling.

In addition to public dances, the hall hosts weddings, anniversaries and events for Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, the Texas Farm Bureau and other ag groups.

The spacious interior of the 12-sided dance hall in Cat Spring.

Dave Shafer

Approximately 200 society members pay $10 annual dues. Up until the 1950s, minutes were recorded in German. Even though women always were involved in the organization’s affairs, they were allowed to join the society just over a decade ago.

“I serve as secretary, and my brother Malcolm Dittert is president,” says Marilyn Nelson, a San Bernard EC member. “Before him, our father, grandfather and great-grandfather were presidents, too. I’ve gone to the hall all my life. While my parents danced, we kids would sleep on pallets under benches, on tables and in the kitchen.”

Since 1856, families have come together for the society’s annual June Fest. The activity-packed evening includes a barbecue supper, live auction, petting zoo and a free dance. “Traditionally, June Fest was held the first Sunday of June,” Nelson says. “But we had to change it to Saturday to make it more convenient for people who travel.

“It’s hard to keep the community involved with the hall and agricultural society,” she adds. “We’re trying to keep it all going. We’ve got to.”

Cat Spring Agricultural Society Hall, 13035 Hall Road, Cat Spring, 78933; (979) 865-2540; catspringagsociety.org.

Texas music legend Johnny Bush and his band bid farewell to dancers at Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall.

Dave Shafer

Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall

Quihi | Served by Medina EC

On a horse-themed calendar, third-grader Savannah Grohman marks birthdays and upcoming dances at the Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall. “She’s been going there all her life,” says mom Jackie Grohman, a Medina EC member. “Sometimes, Savannah helps her grandparents stock sodas and water. Or she and I dance together in a corner.”

Family traditions keep alive country western dances at the tin-sided hall, set on cedar posts among live oaks near Quihi Creek in Medina County. Folks have gathered at the same place since 1890, when German settlers founded the Quihi Schützen Verein for community protection against frontier-era threats. These days, Quihi Gun Club members, who number about 600, still meet regularly to hone their rifle skills and compete in annual shoots.

Folks have gathered at the site of Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall in Medina County since 1890.

Dave Shafer

“Until 1950, you had to speak and read German in order to become a member,” says Clyde Muennink, club secretary-treasurer and Savannah’s grandfather. “We require that members be men at least 21 years old and have lived in Medina County for one year. Since 1890, our club has had a burial fund. When a member passes, we each give a dollar toward burial costs.”

Floods washed away the hall a few times. In the 1960s, the group enlarged the building and set it on 5-foot posts. In a May 2010 flood, 2 feet of water got inside. By the next weekend, members had it cleaned up for a party for a family that had no place else to go.

“I’ve been going to the hall since I was a week old,” says Muennink, a Medina EC member who’s managed the place where he met his wife, Kathy, for 27 years. “My parents met and married there. So did my wife’s. My mother still dances at the hall, and she’s in her 90s. We all grew up there. It’s like home to us. Maybe because it is.”

Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall, County Road 4517, Hondo, 78861; (830) 426-2859; quihidancehall.com.

Correction: January 31, 2019

The story originally said Hank Wilson was one of the artists who got his start in dance halls. His name has been corrected to Hank Williams.