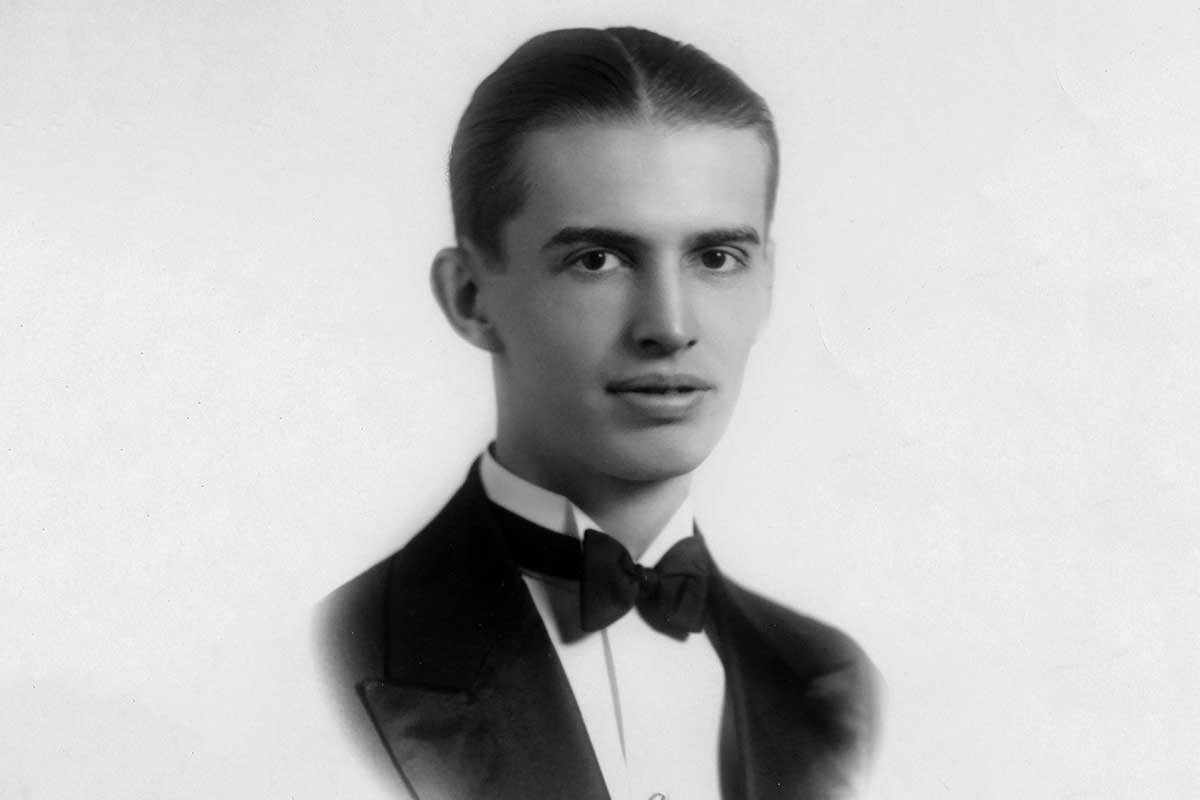

The term “Renaissance man” is used to describe a highly cultivated man (or woman) who is skilled and well-versed in many fields of knowledge. The idea is that the person embodies the idealized qualities of celebrated Renaissance thinkers and artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. During the first half of the 20th century, a Southeast Texan named Larry Jene Fisher seemed to fit that bill, earning him the moniker “Renaissance Man of the Big Thicket.”

A photographer and filmmaker. An organist and music teacher. A playwright and newspaper columnist. An aviator and firefighter. A theater director and environmentalist. Fisher stood out during his half-century of life as a man of vision in a place barely rising from its frontier past.

Fisher directs the play The Keyser Burnout.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

His accomplishments grew from his extreme self-confidence, insatiable curiosity and, as a man of modest means, economic necessity, explains Penny Clark, special collections librarian at Lamar University in Beaumont. Clark maintains the Larry Jene Fisher Collection, a repository of 8,000 scanned images of Fisher’s work, 800 of which are available online (by searching “Larry Jene Fisher” at lamar.edu).

Fisher was born Lawrence Orsino Fisher in 1902, just as an oil boom erupted in the tiny North Texas town of Petrolia, where his mother operated a boardinghouse. A devout German Catholic, his mother moved to Dallas, where she enrolled her son in parochial school. He proved a musical prodigy, learning to play the pipe organ by age 5. At 15 he started working for Warner Brothers and Publix Theatres, traveling the American heartland playing organ music to accompany silent motion pictures, as was the custom before “talkies” brought sound to the silver screen.

He billed himself as Larry Jean Fisher (later spelled “Jene”) and organized vaudeville shows while also playing live on radio stations in several states. When not in Texas, he went by “the Texas Organist” and dressed in Western clothes, playing cowboy tunes.

Fisher studied music under well-known organists and composers and began teaching organ at East Texas State Teachers College (now Texas A&M University-Commerce) by 1930. Fisher soon moved to Southeast Texas, signing on to play a remarkable Robert Morton Organ Company-made organ at the Jefferson Theater in Beaumont, where an oil boom was underway.

A man stands in a field at Lucas Gusher with many oil derricks behind him in 1939.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

For years Fisher played the organ daily for silent films and stage shows while also hosting an organ club for kids. During the 1930s, he operated several music studios in Texas and Louisiana, teaching the accordion, which was very popular at the time. He even formed a group of top students called the Accordionaires, which performed across the region.

“It was music that paid the bills,” Clark says. “But it always seemed like he had 20 other things going at once.”

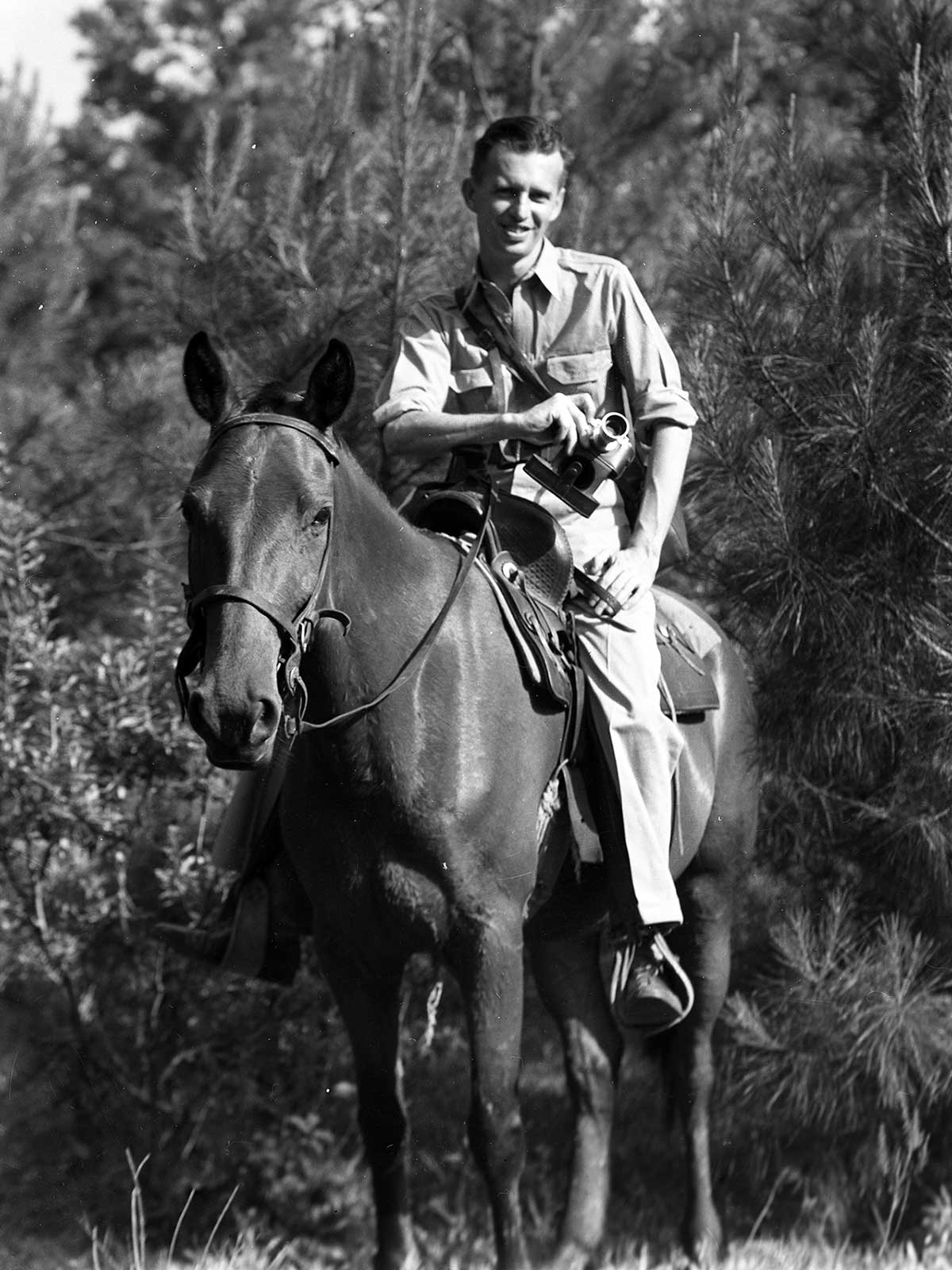

Fisher on horseback.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

Two of Fisher’s favorite activities were photography and aviation. As president of Beaumont’s camera club, he introduced members to color film just as it was being introduced by Kodak. After earning his pilot’s license, Fisher left the Jefferson Theater and opened Larry Fisher Aviation Service. There he gave flying lessons, took aerial photos and took passengers on charter trips and pleasure tours.

Fisher became intrigued by the vast forestland known as the Big Thicket on regular flights from Beaumont to Dallas as he visited his mother. On the ground he quickly learned about its biodiversity and the ancestral traditions of its residents, both of which were disappearing. He met former railroad conductor R.E. Jackson and self-taught naturalist Lance Rosier, joining them in the work of the East Texas Big Thicket Association. The group brought in respected biologists to chronicle the area’s flora and fauna.

The Big Thicket.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

Cameras in hand, Fisher joined their field trips. He showed his treasure trove of photos to community groups, scientists and politicians to drum up interest in creating what is now the Big Thicket National Preserve.

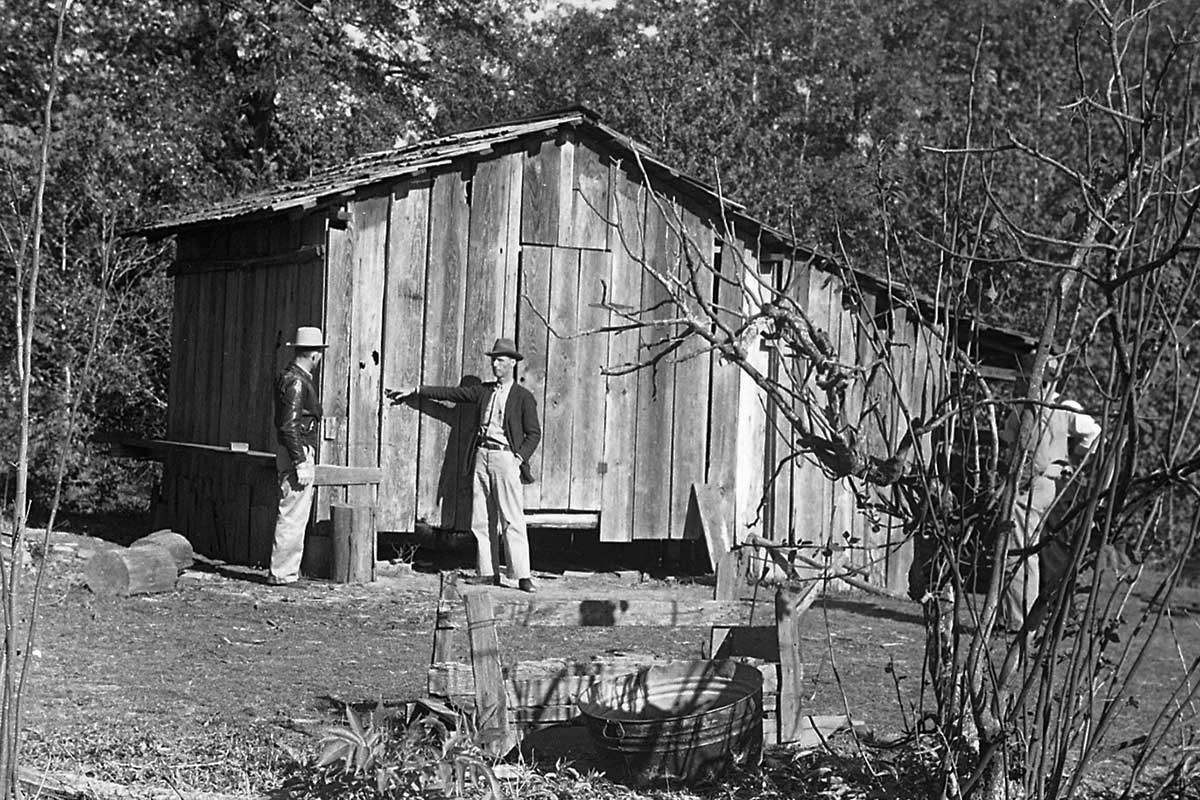

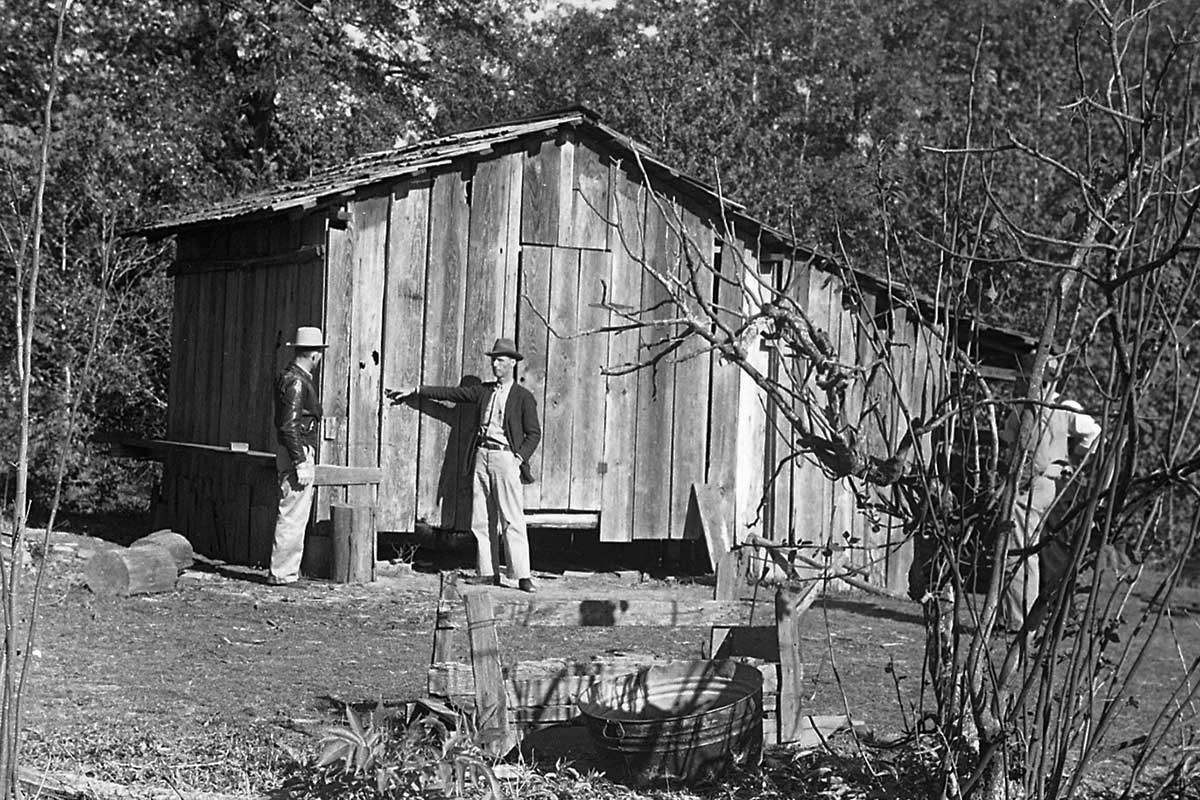

To facilitate his Big Thicket outings, Fisher moved to Saratoga in Hardin County, where he lived for 15 years. At his humble farmhouse, he opened a photography business for taking portraits and recording family funerals, anniversaries, weddings and graduations. He also photographed the waning frontier traditions of the Big Thicket—from syrup making and chimney daubing to free-range cattle raising and stave making. He used his theatrical talents to write and direct a musical drama called The Keyser Burnout about locals who hid out in the Big Thicket during the Civil War to evade Confederate Army service. He also wrote and staged a play about the local oil boom.

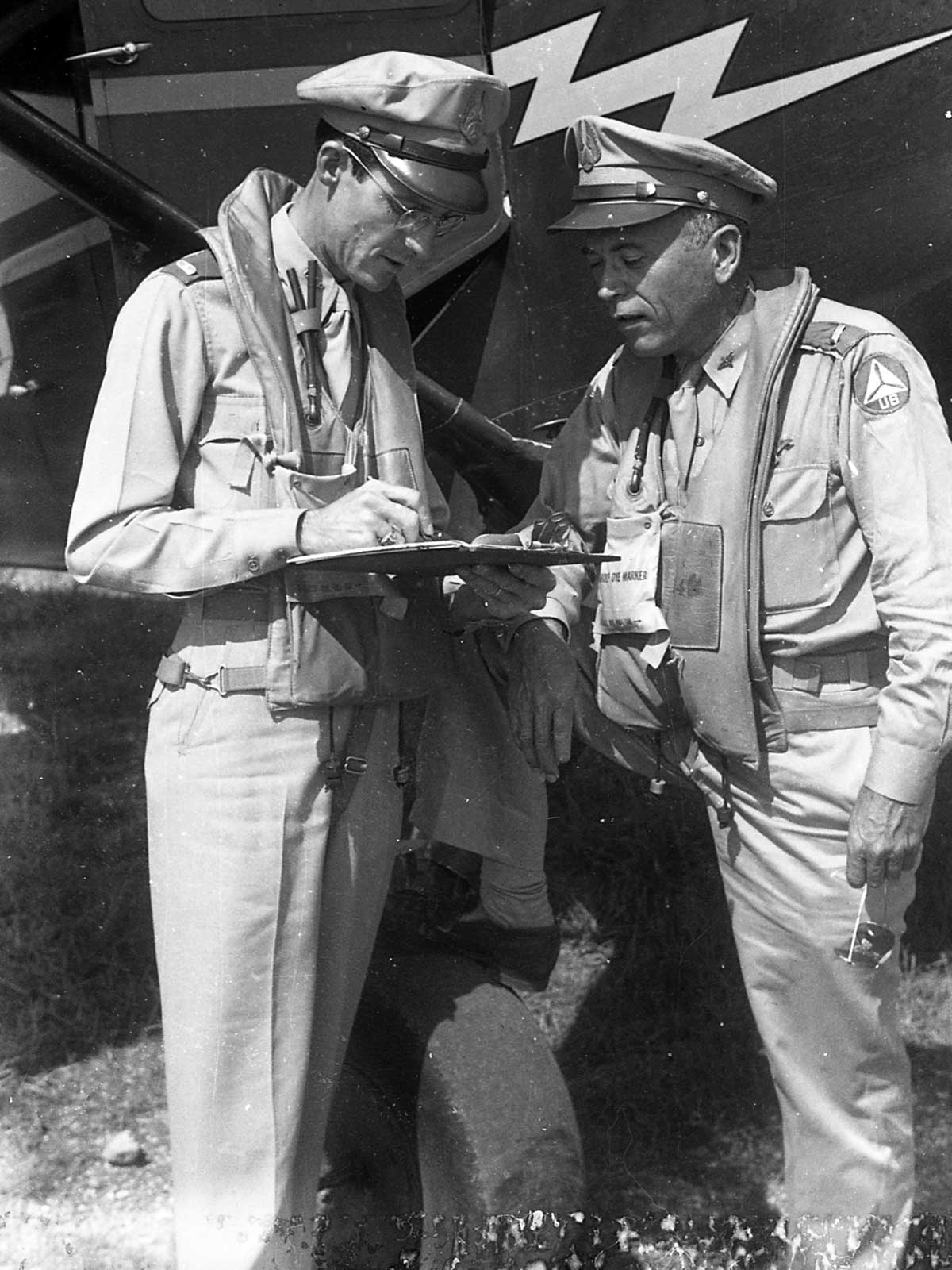

During World War II, Fisher combined his love of photography and aviation. He joined the Civil Air Patrol, a military aviation auxiliary of civilian pilots. Supporting the U.S. war effort, he flew more than 300 hours on missions over the Gulf of Mexico, watching for Nazi submarines.

As archivist and historian for the CAP, Fisher chronicled, in photos, station life at Base 10 in Beaumont. “Whether it was the Big Thicket or the CAP, Fisher understood the need to record what was going on,” says Clark, who used Fisher’s photos to illustrate her book, Beaumont Civil Air Patrol in World War II.

A crowd gathers in downtown Beaumont around a Japanese minisub that was captured at Pearl Harbor and used in a fundraising campaign.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

New opportunities caused Fisher to leave his Saratoga photo studio. He moved to College Station to work for the Texas Forest Service, setting up forest fire patrols. Fisher also headed up an audio-visual department where he produced, filmed and edited topical films.

One project integrated biblical quotes and ideas about forest protection. The short color movie, called Which He Hath Planted, gained high praise in MovieMaker magazine as a top noncommercial film for 1946. (Several of his films can be viewed at texasarchive.org by searching for Larry Jene Fisher.) Fisher continued his film career in Denton in 1949, turning his attention to producing movies and shows for the new medium of television.

A man offers bread to Civil Air Patrol members sitting at a table in 1942.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

Fisher died in 1953 in Nashville, Tennessee, at the young age of 51.

In the early 1970s, well-known Big Thicket activist Maxine Watson of Batson arranged for the Fisher collection of negatives and documents to be archived at what is now Lamar University. The collection had been kept in less-than-ideal conditions near the residence of naturalist Lance Rosier, to whom Fisher gave his works.

A family photographed by Fisher.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

Watson summed up Fisher’s importance in the foreword of the 2008 book Big Thicket People: Larry Jene Fisher’s Photographs of the Last Southern Frontier, by Thad Sitton and C.E. Hunt. “Everything that Larry did attracted friends and attention,” she wrote. “He was interested in virtually everything that people did for their livelihoods and for their amusement. He seemed compelled to record every living thing that grew.”

More than 50 years after the collection arrived at Lamar University, Watson added, “Fisher’s photos and his plays provide an exceptional record of the Big Thicket region—its folklife, its nature, its history, etc. The opportunity to save the record in the Lamar Library was one of the most outstanding and significant acquisitions.”

The hideout of Big Thicket outlaw Thomas J. “Red” Goleman, a simple wooden building, in 1940.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

Civil Air Patrol members examine a flight plan in 1942.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

Fisher’s house in Saratoga.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections

The hideout of Big Thicket outlaw Thomas J. “Red” Goleman, a simple wooden building, in 1940.

Courtesy Larry Jene Fisher Collection, Lamar University Archives and Special Collections