When Sam Houston’s youngest son, Temple, spoke at the state Capitol dedication in 1888, he waxed eloquent about the grand building. “Texas stands peerless amid the mighty, and her brow is crowned with bewildering magnificence!” he said. “This building fires the heart and excites reflection in the minds of all.”

Houston also commented on the logistics required to manifest this structure, which started with the creation of the 3 million-acre XIT Ranch and included the construction of the Austin and Northwestern Railroad to deliver red granite for the Capitol from Marble Falls to Austin.

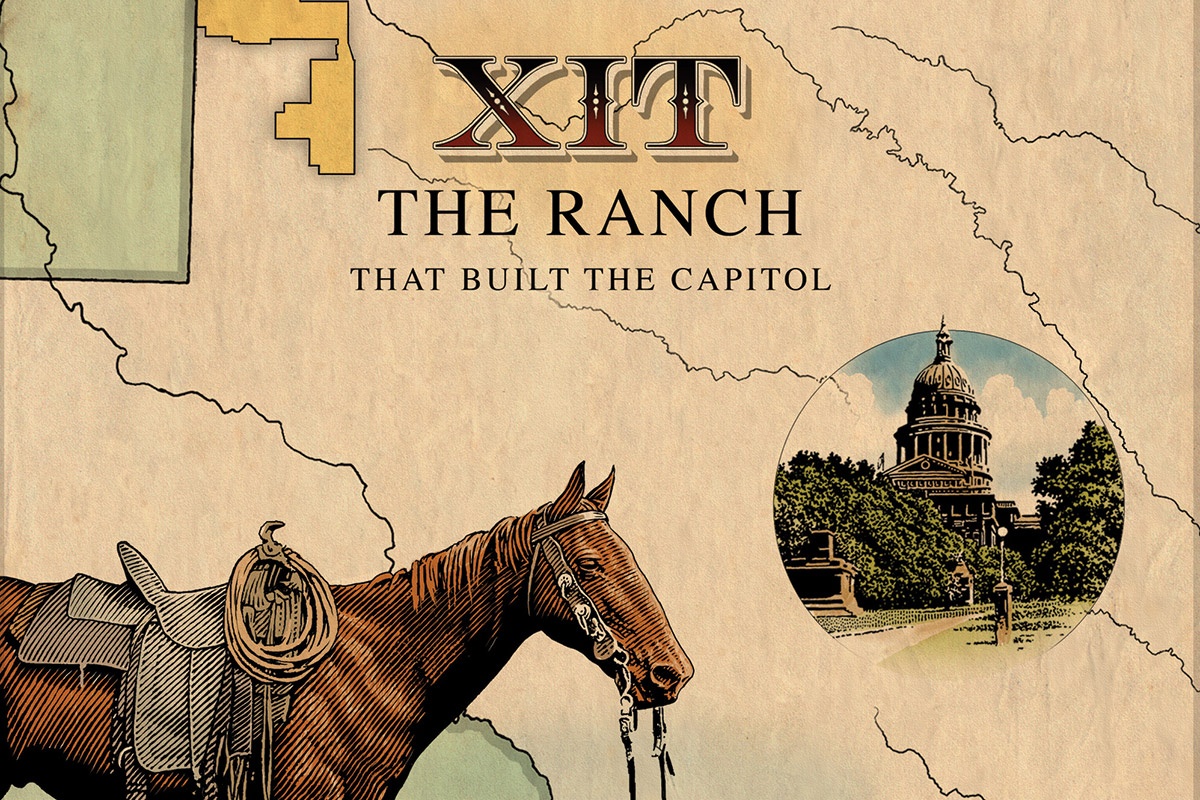

“The XIT looms large in Texas mythology and ranching history because it was the largest fenced ranch in the world during its heyday,” says Nick Olson, director of the XIT Museum in Dalhart, which preserves images, stories, saddles and artifacts associated with the XIT. “And it’s the ranch that built the largest state Capitol in the country.” At the time of its dedication, the Texas Capitol was the seventh-largest building in the world.

Neither the XIT Ranch nor the special, narrow-gauge railroad tracks exist today. The XIT lives on as a carefully tended legend, and the reality of the ranch is difficult to separate from the myths. Capitol and XIT historian Bill Green says the ranch’s legacy can be seen as a branding tool because businesses in Dalhart and around the Panhandle adopt the name: XIT Roofing, XIT Real Estate, XIT Feeders, and XIT car dealerships and communications companies. Thousands of area residents own small patches of the fabled ranch. Cattle outfits operate on lands purchased from the original XIT acreage.

Moreover, the XIT legacy looms globally. “I was curator of history at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum for 17 years,” Green explains, “and we had visitors from all over the world. They all knew two things about Texas: the Alamo and the XIT.”

Building the Capitol

State Legislators realized they needed to plan for a new Capitol in the 1870s, and the Texas Constitution of 1876 set aside 3 million acres of land along the western border of the Panhandle to fund its construction. Even though they allocated the land, they did not articulate a procedure for how to survey the land and execute the legal agreements required to construct the building itself. In 1879, the Legislature approved a process for surveying the land and moving forward with a working plan. Not long after the existing Capitol burned in 1881, the newly appointed Capitol Board, including the governor, treasurer, attorney general and land commissioner, solicited bids.

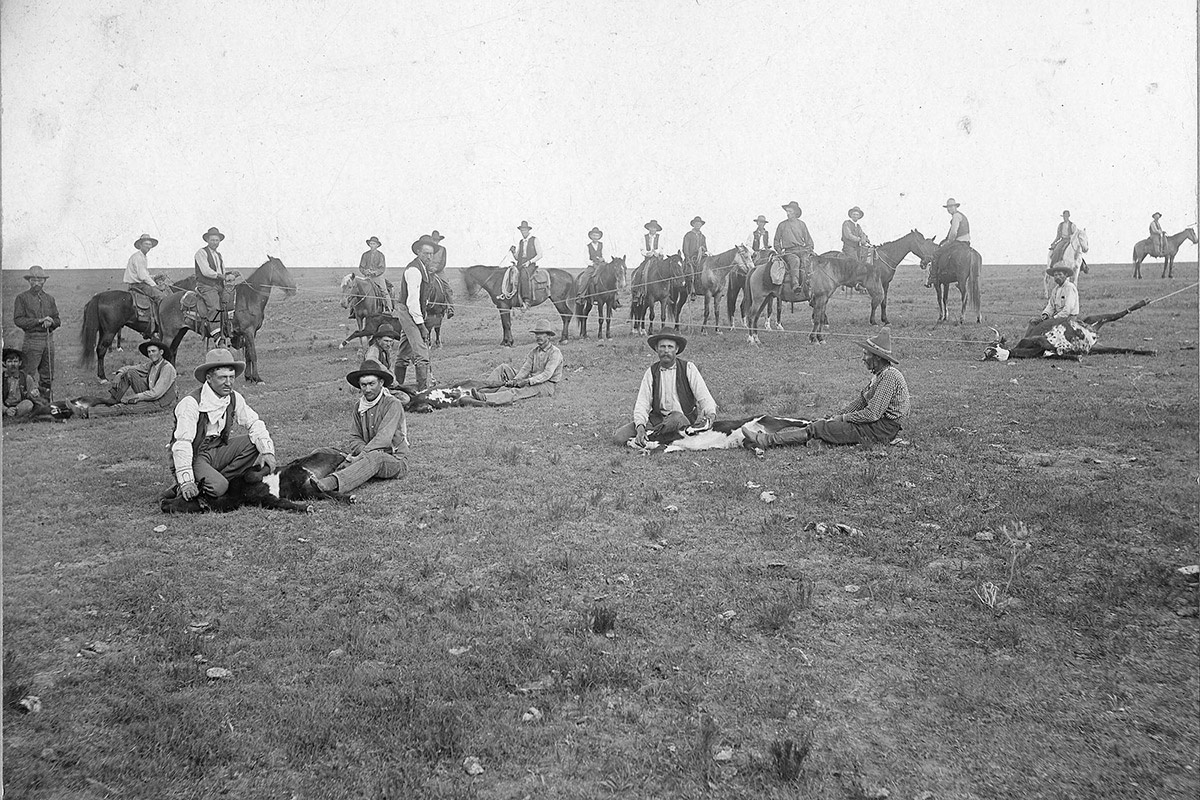

Web Extra: Cattle on the XIT Ranch.

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

In 1882, the contract to construct the edifice went to four Illinoisans: brothers John and Charles Farwell, Amos C. Babcock and Abner Taylor, who formed the Capitol Syndicate. Taylor then hired a 27-year-old German immigrant named Gustav Wilke to serve as contractor. In 1885, the syndicate made an agreement by which it could occupy and ranch on the XIT land even though it did not yet have the title to it. Once the Capitol was complete, the legal title would be conveyed from the state to the syndicate.

To finance the cattle ranching, John Farwell formed the Capitol Freehold Land and Investment Company of London. He and his partners raised about $5 million to keep the ranch running until it could be broken up and sold to individual ranchers and homesteaders.

Back in Austin, construction started on the Capitol, with the Farwells paying for the initial stages from their own funds.

As Green points out, Europeans of the time had a rather romantic view of Texas ranching, and British investors had bankrolled several large Texas ranches, including Charles Goodnight’s JA Ranch. The British Empire enjoyed global reach, and there was little opportunity to pursue the promise of such lucrative investments at home.

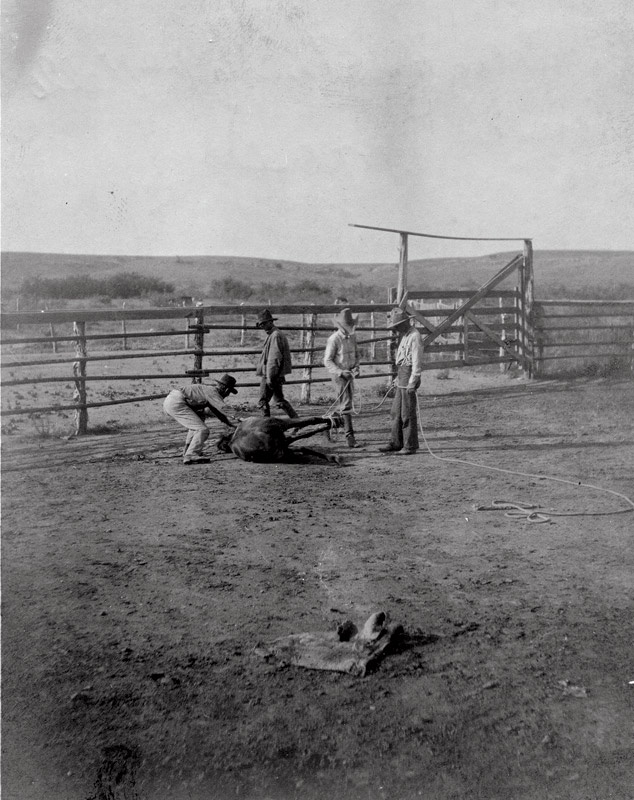

Operating the Ranch

The first longhorns arrived on the XIT range in 1885, delivered by a team of drovers led by Ab Blocker. J. Frank Dobie wrote that Blocker was “the most original-natured trail boss I have known.” At the third XIT Reunion in 1938, where aging cowpokes gathered to swap tall tales and reminisce, Blocker told Lewis Nordyke, author of the 1949 XIT volume, Cattle Empire, that he sketched the XIT brand in the sod with his boot heel for the ranch’s manager at the time, B. H. “Barbecue” Campbell. Blocker demonstrated for Campbell that the brand could be accomplished with five applications of a straightline branding iron and would be nearly impossible for rustlers to alter. XIT it was.

Web Extra: Cattle gather around a windmill on the XIT Ranch.

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

In his 1929 book, The XIT Ranch of Texas, J. Evetts Haley explained that managing the sprawling ranch posed huge challenges for Campbell. “Barbecue exercised slight control over his men and allowed the ranch to become a rendezvous for rustlers, outlaws, and hard cases of all kinds,” Haley wrote.

Ranch operations improved when Albert G. Boyce, described by Haley as “a frontier cowman of commanding presence and vast experience,” became manager of the XIT in 1888. When Boyce took over, he fired and replaced most of the ranch’s 150 cowboys. At the same time, John Farwell improved profitability by replacing the ranch’s longhorn herds with Hereford, Angus and other purebred stock.

Web Extra: Cattle branding on the XIT Ranch.

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

To further streamline the XIT’s business, Boyce divided the massive ranch into eight sections, each with a separate function, and established ranch headquarters in the town of Channing, where he built a house. The northernmost section was named Buffalo Springs. The others included Middle Water, Ojo Bravo, Alamasitas, Rita Blanca, Escarbada and Spring Lake. The southernmost division was Yellow Houses, named for nearby limestone formations called las casas amarillas.

Cowpunchers, well drillers, windmill toilers and freighters—who kept the ranch’s remote outposts equipped with necessities—came from all walks of life. One cowpoke was even said to have a special love for the poetry of John Keats. When Boyce’s daughter Bessie opened a letter from a farm boy in Maryland who professed to love horses, she hired him by return mail. A hand named Blue Stevens later recalled that he gathered cow chips—used as fuel—for 21 days straight, picking up enough chips “to heat branding irons for every cow in the U.S.A.”

Noted ranching photographer Ray Rector cowboyed on the XIT as a youth. According to the 1995 volume The Papers of Will Rogers, the cowboy philosopher worked on the XIT around 1901. A photograph of Yellow Houses’ chuck wagon dining includes an hombre identified as Rogers, who later recalled the Plains as “the prettiest country I ever saw in my life.”

Operating under threat of receivership by British investors for most of its existence, the XIT began selling off its acreage in 1901. The last cattle left the ranch in 1912. In 1936, the first XIT Reunion drew a crowd to Dalhart, and the annual event is now known internationally as “the world’s largest free barbecue.”

The Escarbada division headquarters building—deconstructed, moved, reconstructed and restored—can be seen today at the National Ranching Heritage Center in Lubbock. The XIT general office and manager’s residence still stand in Channing, where an annual Christmas in July event began in 2018. (The 2020 event will be July 25.) The Capitol Visitors Center in Austin features a display on the XIT story.

Was the XIT too sprawling and massive to be a successful ranching operation? Manager Boyce thought so. But Andy Wilkinson, playwright of Charlie Goodnight’s Last Night, takes a longer view. “When you let all the big windies about the fabled ranch drift off into the sunset,” muses Wilkinson, “what still remains is a spread of 3 million acres, 1,500 miles of barbed wire, tens of thousands of cattle, and enough outlaws and heroes and honest-to-goodness cowhands to populate all the rangeland myths of the American West.”

Writer and author Gene Fowler specializes in art and history.