These days, children often play with toys that come from China. Not so for yesteryear’s kids. For nearly seven decades, customers around the world bought model airplanes and other aerial gadgets made by two former farmers in Schulenburg.

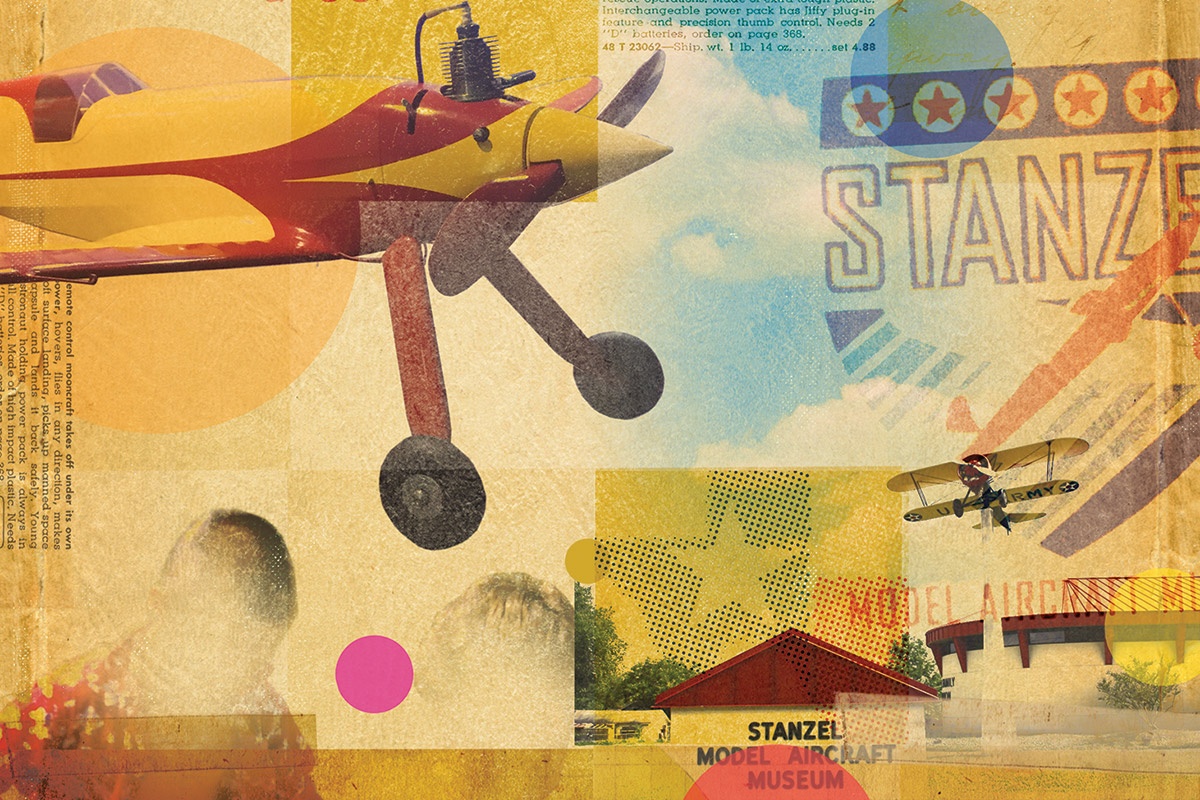

On Baumgarten Street, not far from downtown, a miniature propeller biplane set high atop a slender white column marks the red-roofed Stanzel Model Aircraft Museum. Inside, 30 exhibits share the story of brothers Victor and Joseph “Joe” Stanzel, who manufactured flying innovations ranging from balsa wood airplane kits to spring-powered space shuttles.

“Altogether, they designed 75 different products,” says museum director Lucy Stanzel, who’s married to the brothers’ nephew, Bob Stanzel—both members of Fayette Electric Cooperative. “Every year, they came up with a new toy or packaging design.”

Respectively born in 1910 and 1916, Victor and Joe—along with middle brother Reinhart—lived on their family’s farm east of Schulenburg. After their father died in 1918, the boys and their mother moved to town, but the boys continued to work on their uncle’s nearby farm, picking cotton, tending corn and milking cows. In the fields, Victor studied birds as they winged past, and his fascination with flight included the World War I aircraft that roared overhead on training missions out of San Antonio.

Interest in air travel soared after Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic in 1927. In commemoration, Victor carved a wooden replica of Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis. Victor also studied trade magazines and noted a market for similar model planes. In 1929, he and Joe began constructing “ornamental” models of Army planes, which sold for a then-hefty price of $20 to aviation enthusiasts across the U.S.

Unable to make a profit with ornamentals, they produced model airplane kits, which they priced at $3.50. In a spare bedroom, the brothers packaged each kit’s parts and instructions into cardboard boxes branded “Victor Stanzel & Co.”

To boost sales, Victor designed ads for Model Aircraft News and other aviation magazines. The Stanzels expanded their product line to include military plane kits priced at less than $2. Mail-order sales boomed, and by 1931, their company cataloged 14 different kits and hired two employees.

Victor, 22, had sealed his reputation as a savvy entrepreneur. “This young man does all of his own work and does it well,” the Schulenburg Sticker glowingly reported in August 1932. “He has the fundamentals of a big business man, and we predict a great future for this boy.”

Victor did not attend high school, but when he was 15, he began correspondence courses in drafting, mechanical drawing, algebra and other technical subjects for two years. He also read scientific books and magazines in his quest to understand aerodynamics.

Victor and Joe forged a strong lifelong partnership. “Victor was a man of many talents and abilities,” Ted Stanzel wrote in a biography of his uncles. “He designed model airplanes with precision and attention to detail. Joe was a builder-flyer and possessed unique mechanical capabilities, even without a post-high school formal education.”

In addition to models, Victor designed action-packed rides, which the brothers built. For 25 cents, thrill seekers could soar aboard the Fly-A-Plane Amusement Ride, a full-sized, electric-powered plane Victor patented in 1933. The Stratos-Ship, a six-passenger rocket ship that lifted up and spun in a circle, wowed visitors at the 1936 Texas Centennial and New York’s World Fair in 1939. Victor also patented decorative glass blocks called Glassite and an amusement game similar to pinball.

Aerial toy inventions, though, comprised the majority of Victor’s 25 patents. In 1939, the company introduced the Tiger Shark kit, a gas-powered airplane controlled by a 50-foot-long guideline.

In 1957, after control-line sales dipped, Victor and Joe ended the production of model kits. For the next 40 years, they used plastic-molding machines to manufacture 33 battery-powered aircraft that included helicopters, rockets, jet planes, stunt biplanes and spaceships. These ready-made toys sold in discount stores, grocery chains, specialty toy stores and overseas.

At the company’s peak, more than 125 employees, working in two shifts, turned out 6,000–7,000 toys a day in a factory complex on Kessler Avenue. In July 1990, Joe died, and Victor followed in April 1997. In 2001, the Victor Stanzel Company stopped making its branded Ready-to-Fly toys. “Outsourcing and importing foreign-made products by many U.S. toy merchandisers was a big reason why,” Lucy Stanzel says.

Today, the Stanzel Family Foundation, founded in 1989, awards scholarships and community grants in the Schulenburg area. It also operates the Stanzel Model Aircraft Museum, which includes the museum, the company’s first factory and the 1870 farmhouse of Joe and Victor’s grandparents.

“Our purpose here is to educate and inspire people to follow their dreams,” Stanzel says. “That’s what Victor and Joe did, and it all started as a hobby.”