Carl Hilmar Guenther left Germany for America when he was 22. The year was 1846. He left without telling his parents he was going for fear they’d try to stop him. Young Guenther sailed for America because he thought his future was limited in Germany. He wrote that he “felt hemmed in,” that there was little freedom, and nothing was happening. America, with its promise of infinite opportunities, called to him. “If I cannot see the world in my youth,” he told his parents, “then life won’t mean much to me.”

Upon his arrival in New York, he worked briefly as a laborer and then went to Wisconsin, where he worked in farming and sawmills. The game-changer came when he was able to buy a set of carpenter’s tools for $30. With those tools, he was no longer a laborer. He owned a business.

Guenther then headed south to Mississippi, where he built houses and barns and cabinets, but he didn’t much care for the plantation society he found there. After about four years in the U.S., he thought he might go back to Germany, but first, he wanted to see the place he’d heard so much about: Texas.

In San Antonio, he learned about the German community of Fredericksburg and went there to discover they needed a mill to process the local grain into flour. He had learned the milling trade from his father back in Germany, so he set about building a mill on Live Oak Creek. After borrowing money from his father to buy 150 acres of land, Guenther hired local men on promissory notes guaranteeing future payment for their helping him build a dam, a water wheel, and a mill. Guenther was so honest and reliable that his notes were used as a trustworthy currency in the area.

He married, had children, and because of the success of his mill, they quickly became one of the wealthiest families in Fredericksburg. After a flood destroyed his dam and damaged his mill, he rebuilt it and thought he should build another one in San Antonio, because the city would soon have a population of 10,000 people. It was 1859, and the little city was already a bustling, promising market. Also, the San Antonio River was a more reliable water source.

With the help of Alsatian immigrants from nearby Castroville, Guenther built his new mill. He paid for their labor, in part, with flour futures – the guarantee of future product they’d need. Guenther wrote to his mother that San Antonio was about one-third Mexican, one-third German, and one-third Anglo. His son, he noted, spoke Spanish, English, and German, sometimes all in the same sentence.

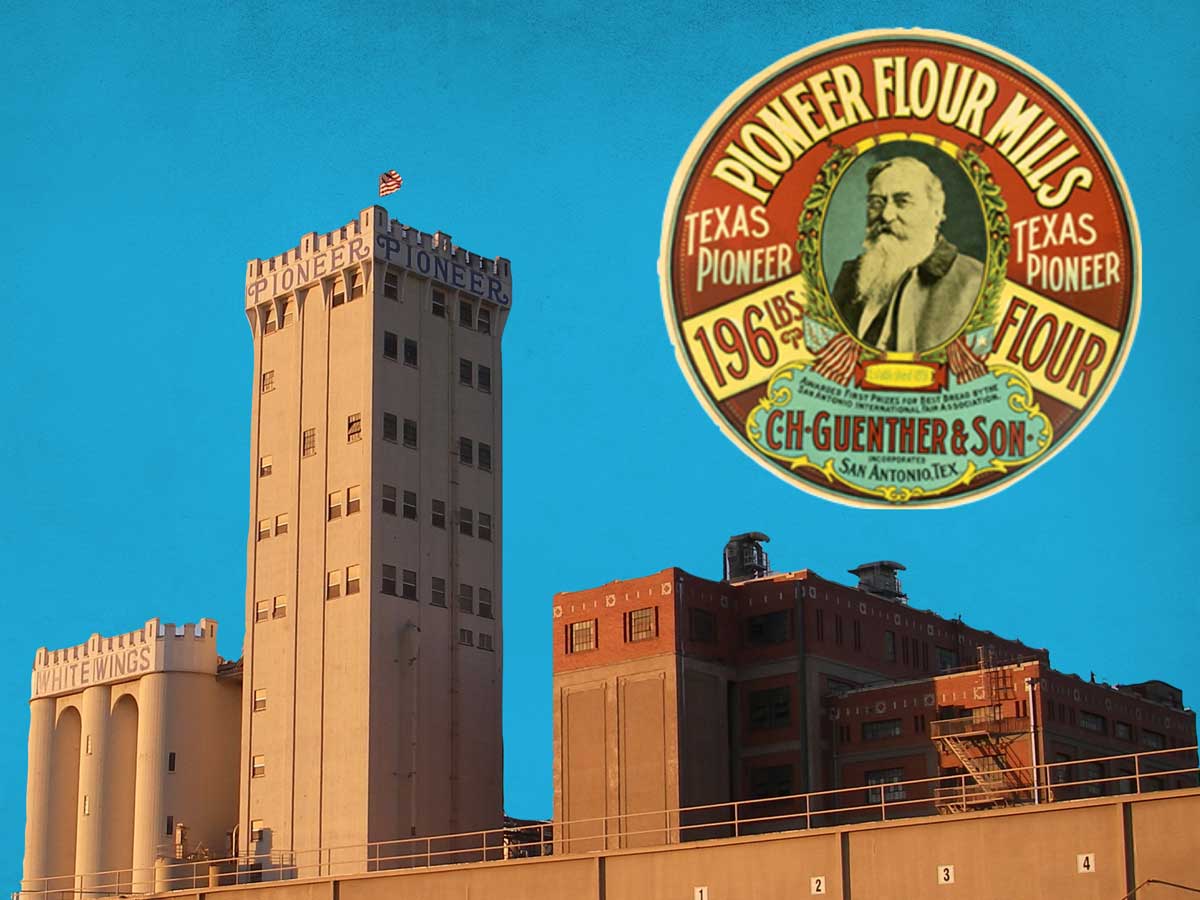

The mill Guenther built-in 1859 is still there in the same spot, much updated, of course. It is now a giant international corporation: Pioneer Flour Mills, doing business as C. H. Gunther & Son, is one of the oldest continuously operating businesses in Texas. You can go there today and tour Pioneer Mills and the original Guenther House, now an exquisite museum and restaurant.

In 1859, the only mechanical element was the water wheel turning the millstones.

Today, the plant is computerized and has robots working collaboratively with people to make flour and flour-based products, like fine gravies, for restaurants and bakeries. Pioneer makes pancake mix for Whataburger, and the Whataburger pancake mix is sold at H-E-B, alongside their own Pioneer pancake mix and Pioneer flour. You may also be familiar with the White Wings (La Paloma) tortilla mix. That’s also made by Pioneer Flour. A subsidiary provides the McGriddle buns to McDonald’s. If you’re from Texas, you’ve certainly tasted their products. Their reach is impressive. A European subsidiary even sells its bread in Germany, where Guenther came from several generations ago.