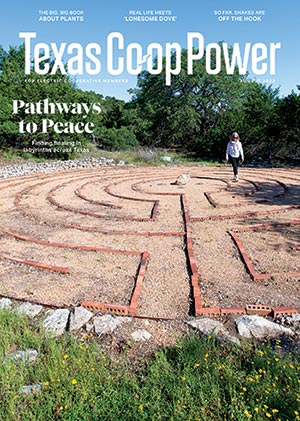

About 20 minutes northwest of Bastrop State Park, a labyrinth lies beneath a grove of towering cedar elms. Seven circles of sandstone, Colorado River rock and honeycomb limestone—all native to the area—comprise what’s known as a Cretan, or classical, design at Bastrop Botanical Gardens. A shepherd’s hook, the name of the long, perpendicular row that leads straight to the bench in the center of the labyrinth, is lined with an eclectic array of rocks and stones, gifts that Deena Spellman received for her birthday in 2012.

Each stone has a story. They celebrate friendships, symbolize memories and mark devastating losses. It was loss, in fact, that inspired Spellman to begin constructing the labyrinth she’d been dreaming of building for more than a decade.

“After the Bastrop County Complex Fire destroyed so many of our neighbors’ and customers’ homes in 2011, I wanted to create a space where people could find some peace and maybe a little hope,” says Spellman, the owner of Bastrop Botanical Gardens, a boutique nursery. “Since then, many people who needed a quiet place to heal have walked the labyrinth. The Cretan part gives you time to contemplate what’s on your mind while you’re walking to the center, or source. The shepherd’s hook gives you direct access. Sometimes you just need to get to source.”

Simply put, a labyrinth is a meandering path leading to a center, a geometric framework for walking, meditation and reflection. Many use it as a tool for personal and spiritual transformation. There are more than 4,500 documented labyrinths in the U.S., according to the World-Wide Labyrinth Locator.

At last count, 240 were listed in Texas—most open to the public, though a handful are private.

Alison Hannah walks the labyrinth at Unity of Wimberley.

Laura Jenkins

Deena Spellman created the labyrinth at Bastrop Botanical Gardens so visitors can “find some peace and maybe a little hope.”

Laura Jenkins

Bastrop Botanical Gardens.

Laura Jenkins

Many Texas labyrinths are situated at houses of worship or spiritual retreat centers, but they’re not just for religious folks. There’s a labyrinth in the meditation garden at the National Vietnam War Museum in Weatherford. The UTHealth Houston nursing school installed one for students as a means of reducing stress. You can find labyrinths at parks, schools and retirement centers.

They’re by no means new. The oldest documented labyrinth dates to 1200 B.C. It was found in Pylos, Greece.

Many conflate labyrinths and mazes, but there’s one major difference between the two. Mazes may offer numerous possible routes to the center, some of which are dead ends. But labyrinths feature only one nonbranching route to the center. One way in, and one way out. They’re ancient archetypes—multicultural symbols that have been found on every continent except Antarctica.

Robert Ferré, a retired labyrinth builder and author of the book The Labyrinth Revival: A Personal Account, says labyrinths went from being archetypal symbols to walkable structures sometime in the Middle Ages.

“Originally labyrinths were small drawings and illustrations in manuscripts,” says Ferré, who lives in San Antonio and has designed more than 1,100 labyrinths worldwide. “At some point somebody decided to build one large enough that they could walk around in. It became a symbol you could embody.

“I think labyrinths reflect a spiritual need in a society that has wandered into living too shallowly, or on the surface of things,” he says. “They signal our need to go deeper.”

Using a labyrinth as a means of self-reflection is something Karen Knight knows a lot about. She’s a certified labyrinth facilitator and co-owner of Ardor Wood Farm in Red Rock. She became interested in labyrinths in 2011 after visiting Chartres Cathedral in France. Her husband, Graham Pierce, built a labyrinth in the cathedral’s style at their farm for Knight’s 50th birthday, a gift that their camping and retreat guests often utilize.

The Rev. Mike Marsh and Brenda Faulkner, director of programs at Children’s Bereavement Center of South Texas.

Laura Jenkins

The St. Philip’s Episcopal Church labyrinth in Uvalde.

Laura Jenkins

Knight also offers “labyrinth magic” experiences, wherein she guides people through the labyrinth using the Veriditas method, which she learned from one of the world’s foremost labyrinth authorities, the Rev. Dr. Lauren Artress.

“Before we begin, I encourage people to start in a place of gratitude and to keep the three Rs in mind: releasing, receiving and returning,” Knight says. “You’re releasing on the way in during your walk. Perhaps there’s a specific thing you’re letting go of, or maybe you’re just releasing the busy chatter in your head. You’re receiving and staying open while you’re in the middle, and as you return you’re taking your experience home.

“I feel like it’s a moving meditation,” she says. “People need a pause. We’re often busy, depleted or distressed, and labyrinths can bring a profound sense of renewal and peace.”

The Rev. Mike Marsh was sold on the benefits of labyrinths long before he became the rector of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Uvalde in 2005. Nine years later, he and Ferré designed and built one for the church. It was a gift to the community, and now it’s a place of respite in the aftermath of the 2022 Robb Elementary School shooting.

“I’ve seen many individuals and families linger there over the years,” Marsh says.

San Antonio-based Children’s Bereavement Center of South Texas uses a church building that is adjacent to the labyrinth to serve children in the community struggling to cope with trauma and grief. They’ve committed to a presence of at least five years in the small town. Brenda Faulkner, the director of programs, moved to Uvalde to take the job—not only because her son, daughter-in-law and two grandsons live there but also because she wanted to help the community heal.

She had used labyrinths as a therapeutic tool for years, so using the one at St. Philip’s with some of the children came naturally to her.

Labyrinth guru Robert Ferré.

Laura Jenkins

A suspended sculpture by Lewis deSoto creates a labyrinth in shadow on the University of Texas at San Antonio’s downtown campus.

Laura Jenkins

“I’ve found that walking the sacred path, which is what Mike calls their labyrinth, serves a couple of purposes,” Faulkner says. “One is that it gets us outdoors. We have a lot of beautiful days in Uvalde. At the beginning of the path I say, ‘I’m old, so you’re going to have to go slower for me so I can keep up with you.’ And as we walk, we talk. It’s also great because it’s a very physical thing. As they’re moving and we’re talking, they’re often not even aware that the therapeutic process is going on.

“What’s interesting about walking a labyrinth,” she says, “is that just about the time you think you’re done, you’re only a quarter done, which kind of correlates with the grief process.”

Marsh has observed the same thing.

“There’s a metaphor in the walking,” he says. “If you follow the path, you’re not going to get lost. You may get disoriented because it looks like you’re getting almost to the center and then you’re way out on the periphery again. But the discipline is to follow the path. Don’t overthink it.”