Here’s something you may not know about Texas:

Way back in 1719, the Marques de San Miguel de Aguayo proposed to the king of Spain that some 400 families be transported from the Canary Islands; Galicia, a region in Spain; or Havana to help populate the province of Texas, which was wide open for such a venture since hardly anyone lived here. The king thought this was a splendid idea and sent a number of Canary Islanders on their way, but, as kings are wont to do, he changed his mind.

By that time, 55 or so Canary Islanders already were well on their way to this wild and thinly populated province. Under the leadership of Juan Leal Goraz, they made their way to the presidio San Antonio de Bexar. They decided to settle near the fort, and their community, Villa de San Fernando, in 1731 became the first chartered civil settlement in Texas. Goraz became the first mayor, and San Fernando was on its way to becoming a city—San Antonio. Many present-day San Antonians trace their roots back to those original Canary Islanders.

Who knew?

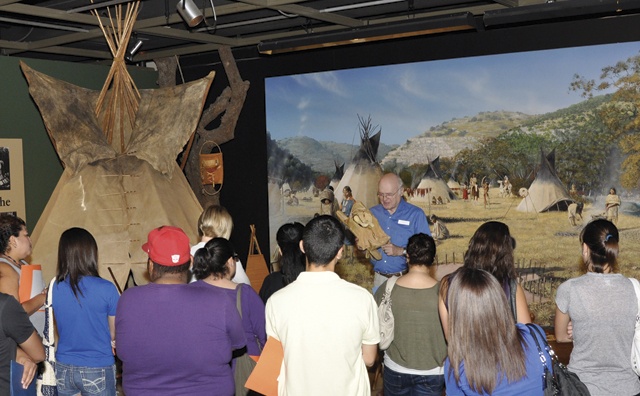

The people at the Institute of Texan Cultures did. It’s one of hundreds—thousands—of stories the institute is dedicated to tell. The Canary Islanders exhibits make up just a smidgen of the tributes and stories about what makes Texas what it is—a land settled by immigrants from nearly every country.

Aaron Parks, assistant executive director of the institute, said that a lot of visitors—out-of-staters and foreigners—expect to see a different Texas from what they see in downtown San Antonio. At the institute, he said, they can get a glimpse of the whole state in a single visit.

“We try to provide a real perspective about Texas,” he said. “Most visitors know Texas is Anglo and Hispanic, but what they realize here is that Texas is incredibly diverse and was settled by people from everywhere. People migrated here and are still coming here, looking for opportunity, and they have helped turn Texas into the 15th-largest economy in the world. It’s really a remarkable story.”

Visitors who don’t necessarily know what the institute is all about get an inkling when they drive up and see period flags from Germany, Mexico, the Czech Republic, Poland, Ireland, Switzerland, Sweden, Spain and other countries flying out front. There are a lot more than six flags over Texas here. Inside, some 40 cultures, including Native Americans and African-Americans, are represented, as are Aleutians, Wends, Belgians and Japanese.

Japanese immigrants were among the first rice farmers in the state. They settled along the Gulf Coast in the first decade of the 20th century, bearing with them seed as a gift from the emperor. Their rice produced considerably more barrels per acre than did native seed. They sold their first three years’ harvest as seed to farmers in Texas and Louisiana, thus creating the Gulf Coast rice industry.

Who knew?

The ITC is in downtown San Antonio in HemisFair Park, at the corner of East Cesar Chavez Boulevard and Tower of the Americas Way. It’s in a building that served as the Texas pavilion during HemisFair ’68, in the same general area where the Canary Islanders set down their roots. The ITC was established by the Texas Legislature in 1965 as part of the state’s participation in the world’s fair, with exhibits devoted to the state’s history, culture and resources. The ITC was put under The University of Texas System in 1969, and in 1973 UT San Antonio assumed the administrative functions of the museum. The ITC library, on the third floor, is operated and run by UTSA and features manuscripts, rare books, personal papers, more than 3 million historical photos, more than 700 oral histories and the university archives. “UTSA brings us a ton of expertise,” Parks said.

The institute’s signature event is still the Texas Folklife Festival, which celebrated its 41st anniversary earlier this year. R. Henderson Shuffler, first director of the ITC, saw the festival as a way to bring people to the institute and expose them to the story it was built and designed to tell. “No matter how different or divergent our ancestry, we are all Texans,” Shuffler told reporters at the time of the festival’s founding. “This is all the Institute of Texan Cultures ever had to say, and the Texas Folklife Festival seems to be a good way to tell it.”

Jo Ann Andera was at the first Texas Folklife Festival in 1972. She appeared with a group of Lebanese folk dancers who moved their feet and bodies and twirled their colorful skirts in the time-honored way—but in a country where belly dancing was less common. Andera was there partly because O.T. Baker, the festival’s first director, helped represent Texas at the Smithsonian Institution’s folklife festival in 1968.

The institute hired 18-year-old Andera as a multilingual tour guide. She helped Baker connect with the Lebanese community in San Antonio and cashed in some vacation days to perform at that first festival. For the past 30 years, she has served as its director. And why not? In many ways, the story that the ITC is dedicated to telling is Andera’s own story. She grew up in a bilingual household where she learned to speak Lebanese and Spanish before she learned English. She said that working for the institute for 40 years and directing the festival for 30 has made her realize that the institute’s stories are as ongoing and current as they are historical. In some very fundamental ways, little has changed since the early immigrants arrived.

“People are coming to Texas today for the same reason they have always come here—freedom,” Andera said. “Whether it’s freedom of religion or freedom from war or oppression, they come here to make a better life for their families, the same as people have always done. Today, we have a growing Afghan population and a growing Middle East community. In some ways, it’s the same story but for a different time.”

These are also different times for institutions like the ITC that have traditionally depended on state funding. In 2011, the Texas Legislature cut funding for the institute by 25 percent. Parks says that means the ITC will focus more on private donations and corporate sponsorships and less on state appropriations while creating exhibits that focus on the blending of cultures. After all, he said, these groups have interacted with one another to form the Texas we know today.

“The cultural contributions to the state from other countries didn’t end in the ’70s,” he said. “We’re focusing now on education and exhibits that help connect the past with the present.”

With a resource like that, when people react to the news of the day by asking, “Who knew?” visitors to the Institute of Texan Cultures will be able to say they did.

——————–

Clay Coppedge, frequent contributor. His book Texas Baseball: A Lone Star Diamond History from Town Teams to the Big Leagues was recently published (The History Press, 2012).

Find more information on the Institute of Texan Cultures, including current exhibits and upcoming events, on the Institute’s website.