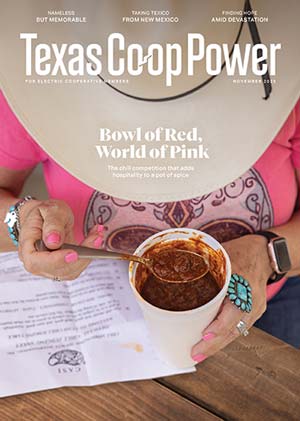

Texans know: Chili is so much more than just a bowl of red.

That wasn’t always the case for Teena Friedel—not many years ago, when she worked for the city of Irving and was tasked with spicing up a city festival.

“I started trying to think of ways to make a festival more fun,” she says, “and one of the things I found was something called a chili cook-off, not knowing what that entails.”

Friedel joined her local pod of the Chili Appreciation Society International to learn the rules and process of a sanctioned competition. After her 2006 event, she remained part of the chapter but was reluctant to get more involved. “They asked me if I wanted to cook, and I did not want to do it,” she says.

After much cajoling and a crash course in cooking chili, she was finally persuaded to compete.

Competition chili typically includes several chili powders.

Julia Robinson

“I made the final table that first day and placed second in showmanship,” Friedel says. She was hooked. “I said, ‘Oh, honey, if I’m cooking chili, I’m going all in.’ ”

The community embraced her.

“If I needed anything, somebody gave it to me, and seeing how much fun everybody had, and part of your entry fee went to charity, and that feels really good.”

In the birthplace of chili, the official state dish comes with a storied history that represents Texas’ bold, rich culture. CASI, one of three standard-bearers for chili cook-offs in the state, hosts hundreds of competitions annually across the continent, raising $729,000 for charity during the last full fiscal year. But none of those events have the vibrance, camaraderie and history of the Texas Ladies’ State Chili Championship Cook-Off.

It’s as much about Texas hospitality as it is secret spice mixtures, and it’s a testament to the power of women in a traditionally male-dominated domain and the close-knit bonds that good food fosters.

Donna Dodgen—Seguin mayor and a contest judge—takes a taste.

Julia Robinson

The TLSCCO holds a unique place in chili history. The event was created in direct response to the 1970 formation of the Chilympiad, a famous San Marcos cook-off that barred women. In response, legendary rancher and humorist Hondo Crouch offered up Luckenbach, the town he owned near Fredericksburg, for a separate cook-off in 1971 called Hell Hath No Fury Like a Woman Scorned. It was for women only. And it was an instant hit.

The event evolved over the years to support more entrants and found its footing in Seguin, about 35 miles east of San Antonio, in 1991 as the second-largest chili cook-off in Texas, just behind the distinguished Terlingua International Chili Championship. While it’s no longer the second-largest, the women’s competition is still a qualifier for Terlingua, meaning winners gain immediate entry to the most prestigious cook-off of the year.

Paisley Banks brings her chili to the judges. The 7-year-old from La Grange won the junior competition.

Julia Robinson

Reese Satsky, wearing her crown from the 2024 junior championship, dishes up her chili.

Julia Robinson

Heating Up

On a warm April day at Max Starcke Park in Seguin, there’s a huge spread of cars, campers and tents, all in residence for the TLSCCO weekend. A flag with the CASI logo flies above the proceedings, centered around a covered pavilion in a grove of pecan and sycamore trees along the Guadalupe River.

With 135 cooks, the competition is fierce but also clearly fun. Tents, tablecloths, T-shirts and décor are in bright pinks, purples and yellows. Previous champions stroll around wearing tiaras and bright sashes. Men, working behind the scenes, wear pink polos. Everywhere is the sound of women laughing.

Under the pavilion, the junior competition is already underway, with four girls ages 7–15 tending their pots in front of the main stage. Last year’s junior champion, Reese Satsky of Friendswood, is back, wearing her crown.

At the appointed hour, they parade their chili through a glitter-speckled purple arch to the turn-in table, reminiscent of a beauty pageant victory lap.

Outside the pavilion, the adult competition is just getting started. Cooks can begin their chili anytime but most plan a three-hour cook for the 1 p.m. turn-in time, when all competitors must present their chili to judges in 32-ounce plastic foam cups, marked only with ID numbers for anonymity. The visiting and socializing quiet down as the burners are lit.

“A lot of people think if you go to a cook-off, it’s just, you know, a free-for-all,” says Beverly Maricle, the cook-off’s board president. “We do party. We do have a good time but take what we do very seriously. After chili is turned in, or during the resting period, then you walk around and you visit with everybody, but when you’re cooking, you’re cooking. It is a competition.”

René Chapa of Grand Prairie, the 2023 chili world champion and 2014 ladies state champion, is among this year’s top competitors, browning her meat on a custom-painted camping stove under a purple awning with six other cooks, including her mom, Beth Baxter. All are dressed in pink shirts that read, “Spread Kindness.”

Chapa coats her plastic foam cup with a spoonful of chili.

Julia Robinson

“Everybody does their own things a little bit differently,” Chapa says. “And so, you know, I’ll tweak it here and there. She tweaks hers here and there.”

While traditional Texas chili consists of beef (usually cuts of stew meat) cooked low and slow with a blend of peppers, garlic and onions, competition chili is more concentrated.

“This chili is not like a Wolf Brand Chili. You’re not going to sit there and eat a whole bowl; it’s very spicy,” Chapa says. “We’ve got five, six chili powders in here.”

Stew meat is left behind in favor of chili ground beef, and any vegetables are blended to create a gravy. Judges taste a single spoonful of each chili before recording a score, so each bite needs to pack a consistent punch.

“Competition chili is a little bit stronger, a little saltier, a little spicier,” says Maricle, a member of GVEC. “You want a little back bite, but if the tears are running down your face, your pot’s too hot.”

Final-round entries at the 2025 Texas Ladies’ State Chili Championship Cook-Off in Seguin.

Julia Robinson

Each entry is judged based on five factors: aroma, color, consistency, taste and aftertaste. At the end of each round of judging, half the entries advance and the tasting begins anew.

Pat Krenek, 2001 and 2003 ladies state champion, has been coming to the competition since the Luckenbach days.

“You have to start out with a decent recipe,” she says. “You crank it up, put it in that cup, turn it in and wish for the best. Once you cook your pot, it’s out of your hands.”

Krenek loves the atmosphere of the event. “This is just a relaxing time. It’s not a beauty contest, so you don’t have to dress up or do your hair and makeup,” she says. “And the men are the ones working.”

Cooking Down

Stoves get turned off during the chili’s resting period as the spices work their magic. And then there’s a last-minute crush of activity before the mad rush to the turn-in table.

At Chapa’s tent, a band of visiting competitors brings out a tray of Jell-O shots, and everyone toasts to each other’s good luck. Some go back for seconds.

About 10 minutes before turn-in time, Chapa primes her entry cup by pouring in a spoonful of chili and swishing it around the edges, coating the cup in a familiar red color. Precoating the cup takes some of the plastic foam smell away, giving the aroma the best chance of scoring high.

At its core, this is a competition, but it’s also about the experience. For the participants, it’s a chance to show off their skills and gain recognition but also to nurture the bonds of a supportive statewide community.

Jeff Bauer, a CASI board member from Pinehurst, is sitting in the shade as his daughter Madalynn Bauer, 18, is cooking in the adult division for the first time. “At barbecue cook-offs, nobody will help you. It’s all about me, me, me, me, me,” Jeff says. “But chili cooks, they’ll help you.”

He competed for years on the barbecue trail before finding the chili circuit.

“It got to the point to where I was spending almost $800, $900, $1,000 a weekend at barbecue competitions,” he says, “and without sponsorship, there’s no way an average Joe can do that.”

An entry in the junior competition gets loving attention from an adult.

Julia Robinson

Bauer made the switch to chili in 2012, bringing Madalynn with him to competitions. “I mean, the chili cook world is just so much more friendly.”

The kindness of the chili community is a common refrain among TLSCCO competitors, many of whom return year after year. There’s an unspoken understanding that while everyone is there to win, the real victory is the chance to support one another.

When Friedel, the reluctant cook from Irving, was diagnosed with cancer in 2011, words of encouragement poured in from CASI members from across the U.S.

“I never felt so much love from strangers in my entire life. I got cards in the mail from Minnesota, Ohio. I don’t even know who these people were, but they knew me from the cook-offs,” Friedel says. “It was just the most moving and precious thing to have people help you when you struggle. I have a whole chili family now.”

Crowning Moment

For judging, hundreds of people—including members of the public—are divided among tasting tables.

“We like to have a minimum of 200,” Maricle says. On this day, some parks employees and litter cleanup crews have been recruited. The mayor of Seguin, Donna Dodgen; city employees; and longtime chili judges line the final table to determine the winners.

The main stage features custom purple camp chairs, part of the award booty for the top 20 cooks.

After the final tastings, the pavilion overflows with competitors, their supporters and curious onlookers. The winners are announced from 20th place to first by the entry numbers on their cups. Sharp cries and shouts of excitement rise up as winners emerge from the crowd, accept hugs from friends and then are escorted on stage.

Beth Baxter’s number is called as 20th place, and she takes a seat in her camp chair. As she’s handed a chilled glass of champagne, the number of her daughter, René Chapa, is called as 19th place, and the two women reunite on stage with laughter and hugs.

Friedel relishes winning the 2025 cook-off.

Julia Robinson

The traveling championship plaque with a growing list of engraved names.

Julia Robinson

The camp chairs are almost full as the reserve champion’s number is called. A proud Jeff Bauer lets out a whoop of joy and spins his daughter Madalynn around. As the runner-up, she will head to Terlingua after her first year of competition.

When the championship announcement comes, Friedel looks radiant as she rises from the crowd. It takes her a few minutes to make her way to the stage, slowed down by all the hugs she receives along the way.

She’s crowned by last year’s winner and handed a bouquet of yellow roses and a large trophy, which she will carry around to competitions until next year’s winner is declared. She dabbled in chili cooking on a lark, and now—with the help of her “chili family”—she’s a state champion.

“I already knew it was going to be me,” she says later. “It was really weird, I just knew I was going to go get that crown.”