Gretchen Riley refers to trees as “who.”

Her subtle personification of living and dead woody perennials reveals how this Texas A&M Forest Service forester and partnership coordinator makes trees relevant to people.

“They have a story to tell, so they have a personality,” she says.

Riley is talking about Texas’ famous trees who were “witness to some of the exciting periods and events in Texas’ frontier history,” according to the first edition of “Famous Trees of Texas” (Texas A&M University Press, 1970). An upcoming edition of the book, due out in early 2015 to correspond with the TFS’ 100th anniversary, memorializes the tales of 100 historic trees.

“I like the famous trees a lot because I love the stories,” says Riley, a Bryan Texas Utilities member. “If trees could talk, this is the story they would tell.”

Across diverse ecological regions—including the piney woods of the east through the post oak savannah, prairies and mesquite regions to the mountain forests in the west—Texas sprouts more tree species than any other state, according to the TFS. Among Texas’ more than 300 native and naturalized tree species stand the ancient, the large and the famous. Riley’s agency educates Texans about forestry and keeps track of exceptional tree specimens.

The oldest trees, such as the 1,000-plus-year-old Goose Island Oak near Rockport, and the biggest, such as the state champion baldcypress near Leakey noted in the Big Tree Registry, earn their credentials based on numbers. Famous trees, however, claim distinction by serving as tangible historical markers.

“The trees are a great way to make it relevant to people today,” Riley says. “People of all ages can go to these places and touch these trees.”

Touching grand and old trees, which are symbols of strength and reminders of God’s creation, she says, is “a bit like sitting in Daddy’s lap.”

Guided by the first-edition book, I hit the road to meet four famous trees. I steered away from trees linked to well-known stories—such as how Stephen F. Austin signed the first boundary agreement with Native Americans under the Treaty Oak in Austin or how Gen. Sam Houston rallied his troops before the Battle of San Jacinto under the Runaway Scrape Oak near Gonzales—and instead visited a variety of species in disparate regions of the state.

Here are their historic stories and snapshots of their present.

Landmark Cottonwood, Canadian

Before permanent settlements came to the Panhandle in the 1870s, a tree on the prairies of the Southern Great Plains had to fight for survival. Sand bluestem, switchgrass and Indiangrass grew on the mostly stabilized dunes of the old prairie, thriving through fires that once flashed the region every seven to 12 years. The blazes would destroy all the woody vegetation, but the grass would sprout again, providing nutritious sustenance to buffalo.

“Fire and grass go together like peas and carrots,” says Texas Parks and Wildlife Biologist Jamie Baker, who lives on the Gene Howe Wildlife Management Area near Canadian.

Mankind’s suppression of fires has allowed more trees to grow among the grass. The Canadian River valley now grows thick with western soapberry, black locust, black walnut and eastern cottonwood.

At Lake Marvin on the federal Black Kettle National Grasslands, Baker hikes near the Canadian River. He steps over the trail’s sun-bleached railroad ties into golden, hip-high grass and looks out over a small meadow rimmed in thicket.

“Transpose it in your mind across thousands and thousands of acres,” he says. “That’s the old prairie.”

On this landscape where historically the horizon rarely interrupted the sky, any large tree would have stood out. The Landmark Cottonwood, which grew in a low wet spot and had thick bark that insulated it from fire, marked a safe crossing on the Canadian River for military and stagecoach travelers heading north to Fort Supply in Oklahoma or south to Fort Elliott, the first permanent settlement established in 1875 in the Panhandle.

“It’s the right kind of tree in the right place at the right time,” Baker says, arriving at a viewing platform above muddy ground. “There’s no mistakin’ it.”

At about 90 feet tall with a trunk more than 6 feet in diameter, the long-living Landmark Cottonwood towers above its neighboring trees. Baker estimates a nearby 80- to 90-year-old elm comes closest in age to this cottonwood, which was mature enough for settlers to notice almost 140 years ago.

Today, the Landmark Cottonwood’s fallen limbs—some as big as the trees around it—lie on the ground among shards of bark as big as hands. The tree’s deciduous soft hardwood has weakened with age, and the elements have taken a toll.

“Evidently, to a large number of people it is a rather important tree, but we just cringe every time the wind blows,” says Curtis Youngman, natural resource manager for the Black Kettle National Grasslands. “I think it’s time to take some pictures of it and document it because I don’t think it’s going to be with us much longer.”

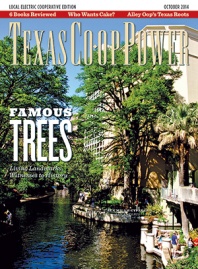

Ben Milam Cypress, San Antonio

On the winding San Antonio River Walk near the Commerce Street Bridge, a baldcypress rivals the height of a multistory Holiday Inn. The famous tree and hotel share a plot on the east side of the San Antonio River.

Here, honeymooners Anthony and Toni Whitlock from Waco stroll along the water and crane their necks to see the tree’s ascending branches.

“These trees must have been here a really long time for them to be that big,” Anthony says, snapping pictures of the deciduous conifer.

He’s right. This towering baldcypress with a forked trunk has been around since before 1835. The Ben Milam Cypress measures about 90 feet tall and has a canopy spread of about 98 feet, says San Antonio City Arborist Mark C. Bird.

Before the Battle of the Alamo, soldier and colonist Benjamin Rush Milam joined the Texas army in the fight for independence from Mexico. In winter 1835, he and the Texans were about to retreat when a Mexican general surrendered, and Milam saw the opportunity to seize San Antonio.

“Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?” he asked, according to the “Handbook of Texas.” Milam rallied 300 troops for the Siege of Bexar.

The victorious four-day fight paved the way for Texas’ independence, but Milam didn’t live to see the success of the siege. After the capture of two prominent houses along the east bank of the San Antonio River, a sharpshooter shot Milam from a perch in the same baldcypress tree that overlooks the Holiday Inn today.

Unlike the Whitlocks, most passersby barely glance at this famous tree. Except for a QR code mounted on a post standing in a pile of cinnamon-colored, feather-like leaves, no memorial marks the spot. Scanning the barcode-like icon on the post with a smartphone app directs the curious to a recording of former longtime TFS Director Bruce Miles telling the tale of the Ben Milam Cypress.

Hubbard Ginkgo, Tyler

In Tyler, City Hall’s front desk employees don’t know which tree on City Hall property is the historic Hubbard Ginkgo.

Gary Lynch in the Parks and Recreation Department, however, can distinguish the tree from among the pecans, oaks and magnolias because he and his wife sometimes share lunch outside in the park-like surroundings.

Lynch describes the ginkgo biloba, a tree species with fan-shaped leaves that dates back to eighth-century China. He pulls up a street view in Google maps and points out the approximately 80-foot-tall living fossil—the only known member left in its genus—growing on the south side of Tyler City Hall just off the redbrick West Ferguson Street.

“It’s especially glorious in fall,” he says. “It turns a canary yellow.”

In spring, the ginkgo’s green leaves ascend almost as high as a nearby magnolia, and the trunk takes about 15 paces to walk around. A bronze plaque on scaly bark with deep fissures honors former Texas Gov. Richard B. Hubbard for the tree’s presence in Texas, far from its Asian roots.

The Hubbard Ginkgo began its life in Texas as a sapling 125 years ago. Hubbard, whose second career was serving as a U.S. ambassador, brought two ginkgos back to Texas from Japan.

“Because an ambassador brought it over, it shows that very early on … immediately we are out and about. We get places,” says the Forest Service’s Riley. “You talk about being from Texas, and people know where you’re talking about, even in other countries.”

One ginkgo was planted at the Texas Governor’s Mansion but did not survive. The other was planted on private property that the city of Tyler later acquired for its municipal building. There, the Hubbard Ginkgo has lived long because it has had the appropriate amount of care, says Riley.

“Surprisingly, the tree is doing really well,” says Tyler City Arborist Luke Porter, who explains that the tree endured a lightning strike and repair in the 1960s plus a spring freeze earlier this year. “We just try to keep it alive and keep it healthy.”

Columbus Court Oak, Columbus

The Columbus Court Oak is famous for something it probably didn’t have anything to do with.

After the Texas Revolution, the Republic of Texas formed Colorado County and sent Robert McAlpin Williamson to hold the first court. Lore remembers that Williamson convened the first session in 1837 under a live oak tree near the present-day courthouse. A few years later under the same tree, the story goes, the circuit judge convicted a thief, who was whipped and branded on his right hand with the letter “T” for “thief.”

Based on this story, the State of Texas marked the site in 1936 with a historical marker that declares: “Beneath this tree the first Court of the Third Judicial District of The Republic of Texas was held.” A second marker added in 1969 identifies the tree as a Texas Historic Landmark.

Yet the earliest account of Williamson’s first court, published by the Colorado Citizen newspaper in 1889, says that the people met in a log house, likely a schoolhouse that survived the Revolution.

Even if the court session had been under a tree, exactly which one is disputed. Some believe that Williamson actually conducted his court under another nearby oak.

“But the charm of the supposed outdoor setting took hold with the public,” wrote local historian Bill Stein in “Colorado County’s Courthouses” (Colorado County Historical Commission, 1991).

Residents revere the Columbus Court Oak for this story, even if it isn’t true.

At festivals held each spring for many years, community members celebrated the story of Williamson’s first court with re-enactments under the Court Oak.

“We know that some of the stories aren’t true or have their facts wrong,” Riley says of the original famous trees book. “Perhaps that isn’t quite right, but there is a story in itself in that the community thinks it’s significant.”

Columbus residents also honor the Columbus Court Oak for its beauty, even though it has been dead for about 30 years.

“Of course it died, which was sad,” says Marian Schonenberg, a lifelong Columbus resident in her 50s and San Bernard Electric Cooperative member. “It was sort of the passing of a good friend. We consoled ourselves locally by planting the new tree.”

Schonenberg and fellow members of the Columbus Garden Club maintain a pocket garden at the base of the old and new trees, which occupy a median on Travis Street. Pink knockout roses, Shasta daisies and Confederate jasmine with white blooms that smell “like heaven” give the garden life, she says.

“It is very sculptural,” Schonenberg says of the wide trunk with smooth bark and three main twisted limbs, now trimmed and nestled in the shade of its replacement. “It is majestic, and you just have to stop for a moment to imagine how grand the tree was when it was alive.”

The Columbus Court Oak will be one of the 100 profiled in the 2015 edition of “Famous Trees of Texas.”

“We still feature the ones who have died,” Riley says. “Once you’re famous, you’re always famous.”

———————————–

Suzanne Halko is a staff writer.