Growing up in the Angelina County timber town of Manning, Bob Flournoy knew about East Texas’ most historic roadway, El Camino Real (or the King’s Highway). Generations of American settlers who headed west overland to the Texas frontier traversed the route now followed by Texas Highway 21. Flournoy’s ancestors were among them, including one who operated a stagecoach inn on the route near the community of Chireno.

Known as the Halfway Inn, it was located halfway between San Augustine and Nacogdoches. Flournoy, a longtime Lufkin attorney and Sam Houston Electric Cooperative member, knew the basics from family lore, but it was only a few years ago that he began to fully appreciate that legacy. That’s when Flournoy and several family members met at Chireno for a tour of the historic Halfway Inn. Walking its creaky wood floors, the Flournoys could feel their family history and that of Texas pour from the inn’s hand-hewn timber walls. “It really came home to us that we have a real connection to the very beginnings of the Republic of Texas,” he says.

Randy Mallory

Indeed, Flournoy’s great-great-grandfather, Samuel Martin Flournoy, moved his large family in the early 1840s from Mississippi to a new home in Chireno, named for Spanish land grant holder José Antonio Chireno. Enslaved people built the two-story structure using longleaf pine and local stones. Samuel Martin quickly became the area’s postmaster, opening the post office in his home.

In those days, mail was delivered via stagecoaches that also carried passengers and freight. It was natural then that the Flournoy home would serve not only as post office but also as a stage stop, inn and center of community life. All sorts of people stopped at the Halfway Inn, including notables such as republic president Sam Houston, military leader Thomas J. Rusk and James Pinckney Henderson, the first governor of the state of Texas.

The old Halfway Inn, west of Chireno, photographed by Chas. B. Witchell, March 13, 1934.

Courtesy Library of Congress

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the house changed ownership several times and eventually became the property of the Granberry family until the 1980s. The Chireno Historical Society then took control and began the arduous process of restoring the venerable structure.

“The inn had been moved, so we relocated it to near its original site, probably about where the stagecoach line’s horses were watered,” says historical society member Kaye Monzingo. The society relocated the 1890 Chireno Baptist Church to the site alongside the Halfway Inn (or Flournoy-Granberry House). Both are available to tour. Call Monzingo at (936) 552-7058 for information.

East Texas Beginnings

In the era before railroads and automobiles, carrying mail and newspapers by stagecoach was the fastest way to keep citizens informed. It was also the quickest way to carry passengers, legal documents and other valuables across the country. Setting up a postal system was, in fact, one of the first actions taken in the 1830s by the new Republic of Texas.

Texas’ first stage line ran 5 miles between Houston and Harrisburg and opened just a year after the Texan victory over Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto. After statehood in 1845, entrepreneurs competed for government contracts to carry U.S. mail. These important contracts drove new stagecoach lines to cross East Texas and later to reach West Texas and beyond.

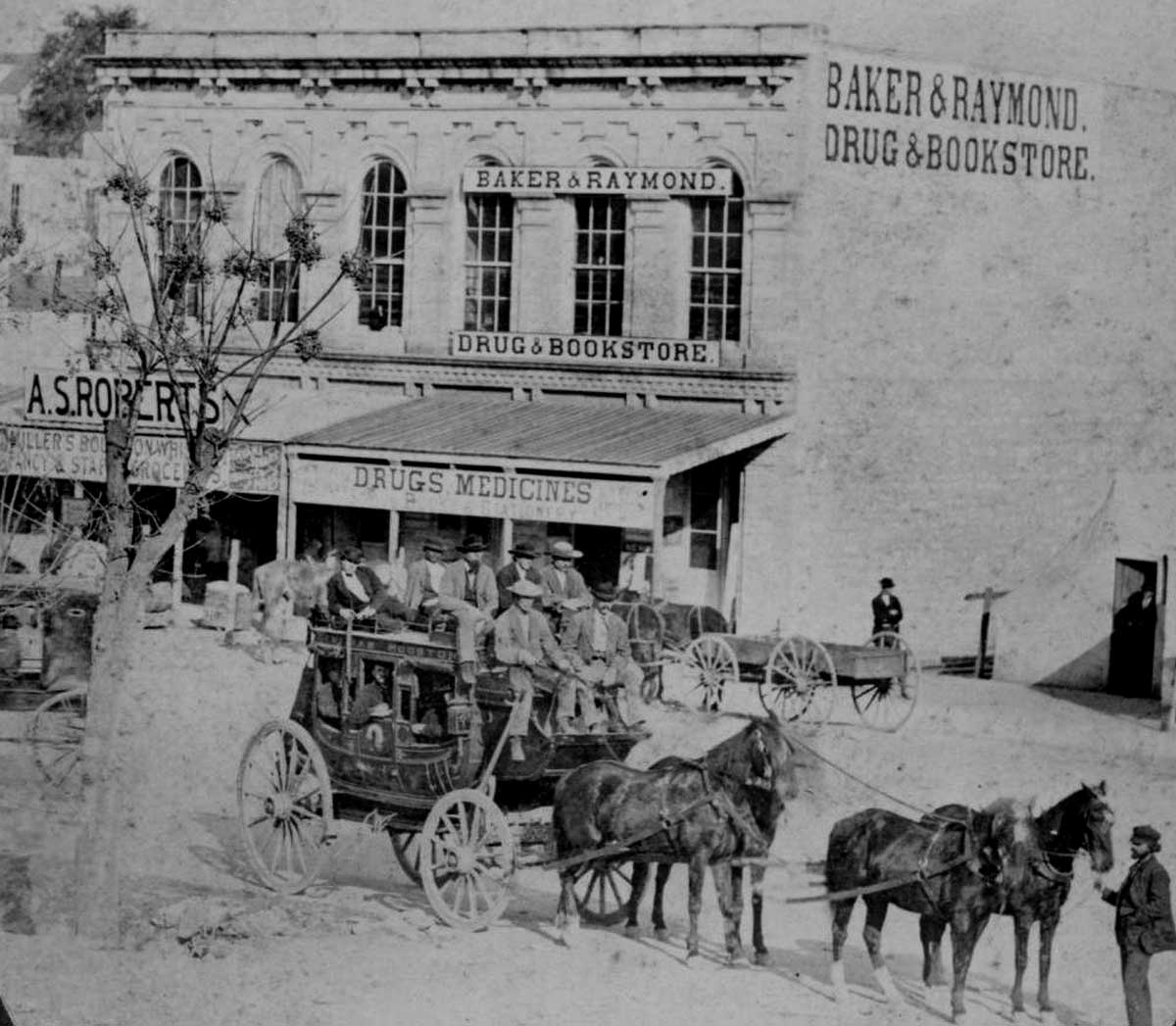

The Sam Houston Mail Coach, photographed by H.B. Hillyer in the 1870s, ran from Austin from 1841 to 1873.

Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

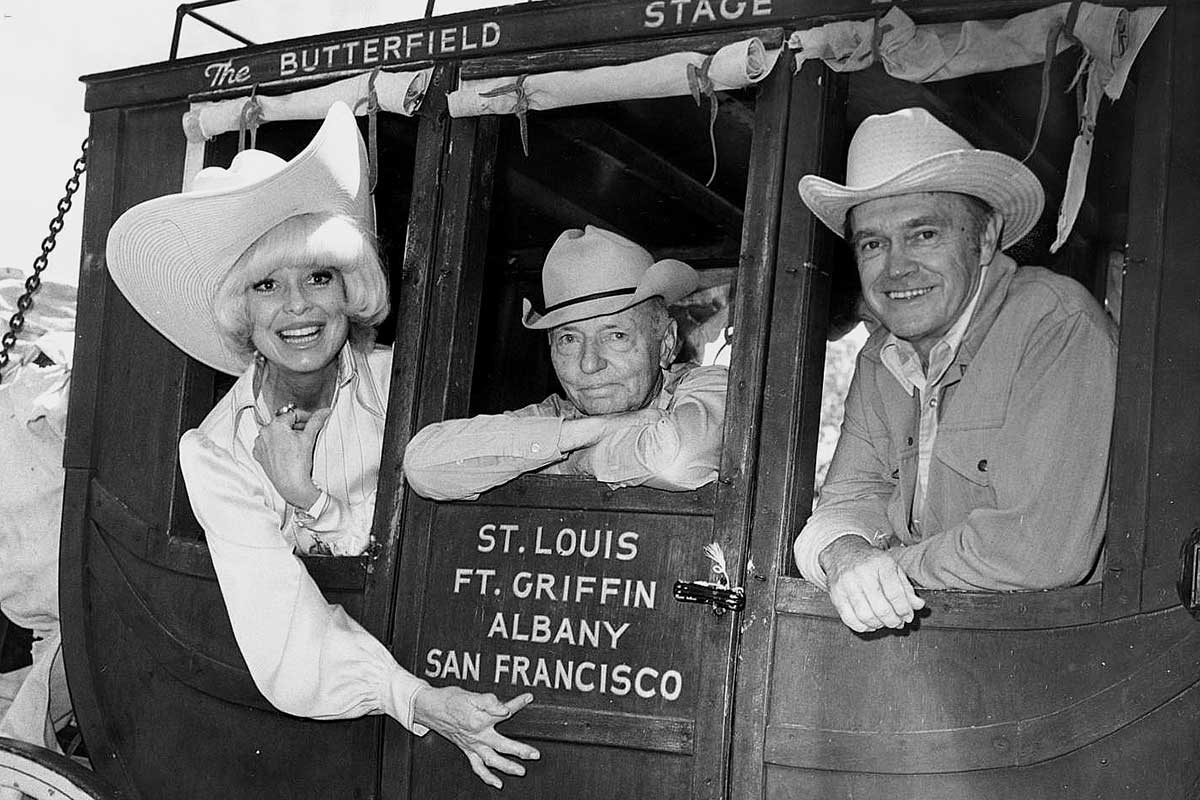

Carol Channing, Watt Matthews and Cactus Pryor in a Butterfield stagecoach.

Courtesy Matthews Family and Lambshead Ranch

The Concord coach—which looked like a teacup on four wheels—became an icon of westward expansion. It was romanticized in movies about the Old West. The Concord typically was painted red with yellow trim along with fancy painting and scrollwork decorating the doors. Four or six horses pulled the coaches, and at stage stops scattered 15–30 miles apart, a driver could hitch up a fresh team of horses to stay on schedule, according to the Texas Almanac.

Passengers could secure meals or even overnight accommodations at inns operated as part of the stage stop. In more populated East Texas, many inns were refined homes, like the Flournoys’, or even elaborate hotels. Out west, stages more often stopped at simple buildings made of local stone or adobe brick.

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 sent a flood of American miners and settlers westward across Texas aboard stagecoaches. The Butterfield Overland Mail Company grew into the state’s largest stagecoach operation, running its 2,795-mile route from St. Louis to San Francisco in 25 days. The route crossed the Red River into Texas at Colbert’s Ferry, near today’s Denison, then traveled eight more days to El Paso, some 740 miles away.

The mail contract was large enough to allow Butterfield to operate 250 coaches pulled by 1,200 horses and 600 mules driven by 800 drivers. To get a feel for stagecoach travel, trek west to the frontier fort of Fort Chadbourne, operated by a private foundation in the small town of Bronte, near San Angelo. There, you’ll find the only restored Butterfield stage stop in Texas, along with other fort buildings from the 1850s and artifacts on display.

Tough Traveling

Stagecoach travel proved jarring at best. Travel tips suggested the best seat as the one beside the driver. Etiquette demanded that passengers avoid slumping over a fellow passenger when sleeping and not constantly asking how far to the next station. Common sense dictated that you not discuss politics or religion.

A postcard shows Salado’s Stagecoach Inn, which it describes on the back as a “major stage stop-relay station of the old Chisholm Trail.”

Randy Mallory

The Halfway Inn in Chireno, built around 1840, sits on Texas 21, the historic El Camino Real, and served as a post office and stagecoach inn.

Randy Mallory

Frequent heavy rainfall in East Texas made stagecoach travel a mucky mess. The bog-prone line from Houston to Austin often required passengers to exit the coach and help push it through deep muddy ruts. To make matters worse, the coaches often carried valuables that made them targets of robberies and—out west—attacks from Native Americans.

To boost business, stage line operators sometimes promised punctuality. Harrison County cotton plantation owner William Bradfield ran stagecoaches between Marshall and Shreveport in the late 1850s. He advertised in local papers that his “line of four-horse Post Coaches runs regularly three times per week from Shreveport via Marshall, Henderson and Rusk to Crockett” and that he featured the best coaches and horses as well as “sober and accommodating” drivers.

The stage ran throughout the Civil War, despite shortages of drivers and horses, and continued until the arrival of railroads in the late 1800s. Many decades of traffic—first by horse hooves and steel-rimmed coach wheels, then by automobiles—left the old stage route deeply worn. You can experience how worn it is today by driving Harrison County Road 2116, which dips in places as deep as 12 feet below grade. The drive is especially popular at Halloween, with reports of haunted sightings along the old road.

The Chireno Historical Society restored The Halfway Inn and offers tours.

Randy Mallory

By the late 1880s, railroads had built thousands of miles of lines across Texas, eliminating the need for stagecoaches in most places. Short stagecoach lines continued to operate after 1900 in isolated places such as the Rio Grande Valley and the Texas Hill Country. The last time a horse-drawn vehicle was used for scheduled transportation came during World War II in East Texas. With gasoline in short supply during the war, the newly formed company town of Lake Jackson started offering horse-drawn wagon rides from neighborhoods to downtown and to schools as well as to the Dow Chemical plant, where most people worked. The Lake Jackson Stagecoach saved residents gasoline and wear on tires, both of which were rationed at the time.

The legacy of stagecoach travel lives on across Texas. A residential community and resort in Montgomery County once served as a stagecoach stop—hence the town name of Stagecoach. The north-central Texas town of Bridgeport once sat where Butterfield Overland Mail coaches crossed the Trinity River.

In tribute, the town got itself named the “Stagecoach Capital of Texas” and houses a replica Concord coach in the town museum. The Grimes County community of Anderson boasts the Fanthorp Inn State Historic Site in a restored 1830s stagecoach inn, open for tours and occasional rides in a replica Concord coach.

Randy Mallory

In early Texas a stagecoach coming to town stirred excitement. A bugle sounded its arrival, and town folks rushed to see who and what had reached their corner of the frontier. Lufkinite Bob Flournoy likes to imagine the scene at his ancestors’ home, the Halfway Inn in Chireno, during the tumultuous yet promising early years of Texas. “Sam Houston was always a hero of mine,” says Flournoy. “I’m proud to think that he stopped at Chireno, shaking hands with my great-great-grandfather right there where we can stand today. Not many people can say that.”

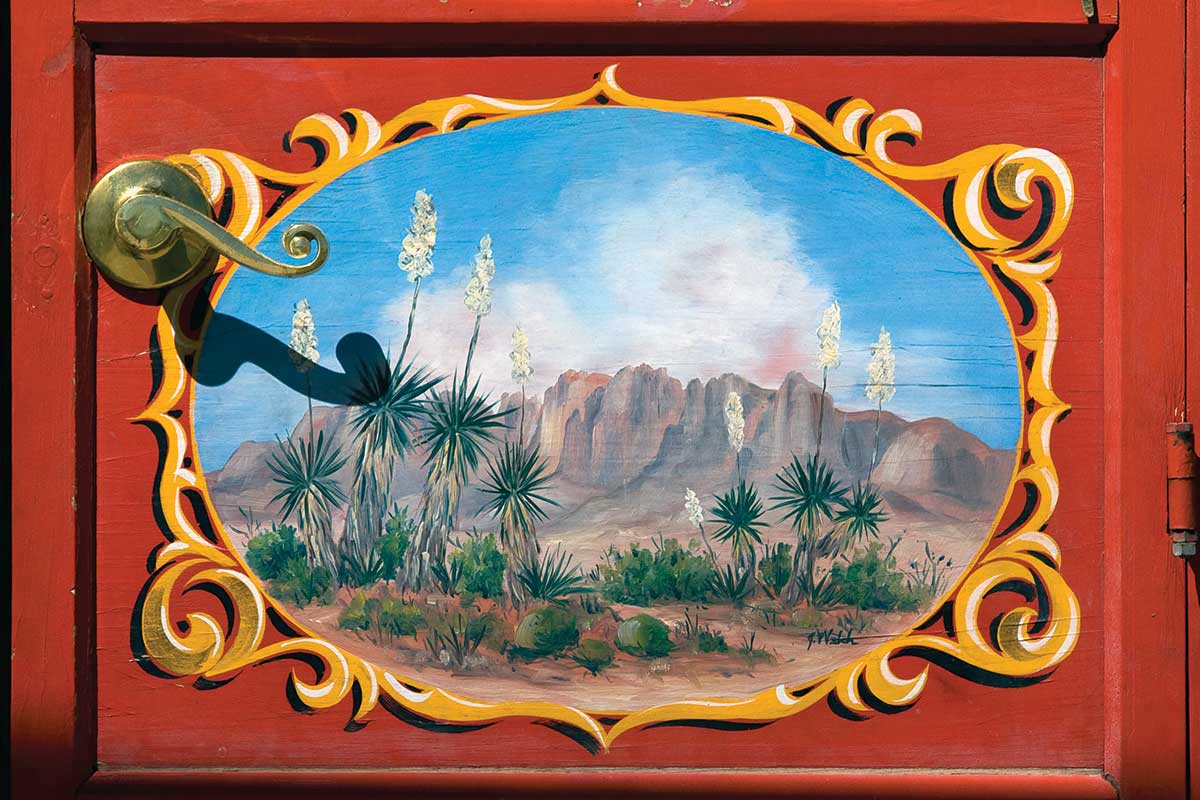

The door of a replica period stagecoach at Fort Lancaster State Historic Site, where a fort was established in 1855 to guard the San Antonio-El Paso Road.

Randy Mallory

A 1911 postcard features the Boerne Hotel, now the restored Kendall Inn.

Patrick Heath Public Library, Boerne

Historic Stagecoach Road (County Road 2116) winds for 6 miles east of Marshall, where horse-drawn coaches and oxen-pulled wagons brought early settlers and mail to the East Texas frontier. More than a century of traffic has worn the single lane as deep as 15 feet into the red clay hills.

Randy Mallory