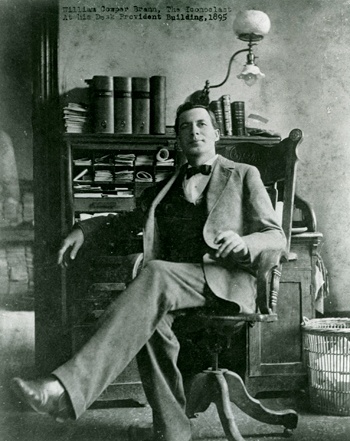

The pen is mightier than the sword, English author Edward Bulwer-Lytton insisted in 1839, but it was no protection against the bullet that buried itself in the back of William Cowper Brann, acid-tongued editor of Waco’s controversial monthly newspaper, the Iconoclast.

As Brann strolled down Austin Avenue in Waco on the evening of April 1, 1898, enraged businessman Tom Davis shouted unprintable epithets, leveled a pistol at Brann’s receding back and fired, hitting him “right where his suspenders crossed,” wrote Charles Carver in “Brann & the Iconoclast” (University of Texas Press, 1957). Brann returned fire.

Both participants in this Wild West-style shootout died of their wounds.

Davis’ daughter attended Baylor University, and the institution was one of Brann’s favorite targets for editorial assault. The defensive father was among hundreds whose threats against Brann had been “thick as the bluebonnets in the meadows,” wrote Carver.

Baylor University, the educational jewel of the Baptist Church since 1845, hit a stretch of rocky road in 1895 after a 14-year-old female student from Brazil working in the home of Baylor’s revered president, Rufus C. Burleson, became pregnant and accused one of Burleson’s young relatives. Brann decried this “brutish crime against the chastity of childhood” and referred to Baylor as “a factory for the manufacture of ministers and Magdalenes,” a comment that didn’t sit well with Baylor’s many supporters, according to Carver’s book.

Brann, who first published the Iconoclast in 1891 in Austin where it went belly-up from lack of interest, was well aware of the boost to circulation that would result from an assault on Baylor. Nothing sells papers quicker than controversy. “Change is the order of the day,” Brann wrote, “and as Baylor cannot very well become worse, it must, of necessity become better.”

Wacoans snatched up the paper for its biting controversy interspersed with bits of wisdom and wry humor. By the late 1890s, almost 100,000 subscribers across the nation and in England, Hawaii and Canada read the Iconoclast.

In October 1897, Brann launched a particularly mean-spirited attack on candidates hoping to replace Burleson, who was retiring as Baylor president, accusing them of “blatant jackasserie.” The scalding commentary prompted a group of Baylor students to kidnap Brann. Several hundred milling students planned to tar and feather him, but someone had gotten wind of the plan and hid the tar and feathers. Frustrated, the students began to chant “hang him.” Only the intervention of some Baylor professors saved Brann, but not before he had been tied up, soundly beaten and forced to sign a promise to leave town by sunset.

Brann did not leave town and took the “Baylor bullies” to task in his newspaper. He planned to let it go at that, but others in Waco did not consider the matter settled. Tempers flared again when Brann offered to teach a night school at Baylor free of charge “… for the instruction of its faculty—if each member thereof will give bond not to seek a better paying situation as soon as he learns something.”

In early April, Brann scheduled a lecture tour beginning in San Antonio. His wife, Carrie, suffered from frayed nerves brought on by the host of threats, and the timing was right for a vacation. The day before they were scheduled to leave, the deadly shots rang out on Austin Avenue.

Hundreds of people lined the streets as Brann’s funeral cortege made its way to the cemetery, preceded by a brass band. No one had ever seen so many people at a funeral in Waco, although it was unclear whether the spectators loved or hated the deceased. A large obelisk was erected above his grave bearing a bas-relief profile of Brann done in marble. Before grass had grown over the grave, an unknown gunman fired a final bullet into the side of the controversial editor’s carved face.

——————–

Martha Deeringer is a frequent contributor who lives in McGregor.