In about a year and a half—December 29, 2025—we’ll mark the 180th year of Texas statehood. That’s the day the proudest of Texans would say the U.S. was allowed to join Texas.

The vast majority of Texians—95%—voted for statehood, a level of agreement we haven’t enjoyed since. President James Polk signed the joint resolution making Texas a state December 29, 1845, but there was some confusion as to the official moment that the Republic of Texas passed into history and statehood status began.

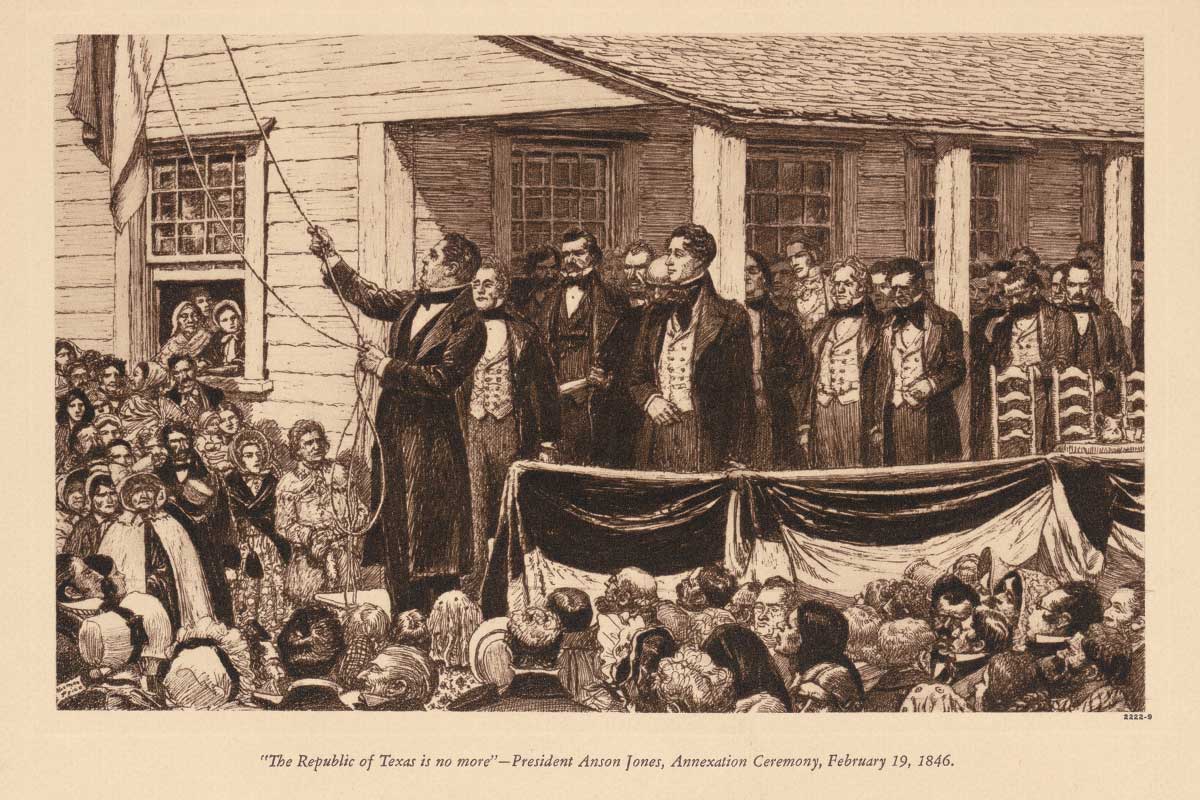

Anson Jones, president of the republic at that time, said that February 19, 1846, was the actual day that the republic ceased to exist. That day, Anson presided over a ceremony in Austin where the flag of the young but venerable republic was lowered for the last time and the U.S. flag was raised in its place.

You see, Texas couldn’t just let President Polk’s signing of a document 1,300 miles away be all there was to the moment. They couldn’t allow the republic that so many had died for to pass into history without properly memorializing the occasion.

Listen as W.F. Strong Narrates This Story

Visit Texas Standard for more W.F. Strong stories (most of which are true).

So Jones arranged a ceremony in front of the Texas Capitol, really just a wooden house at that time, to mourn the passing of the republic and to celebrate Texas as the newest (and by far the largest) state in the union.

What was needed here was what linguists call a speech act, a moment in time where something is made real by virtue of pronouncement.

Jones began with “I, as president of the Republic … am now present to surrender into the hands of those whom the people have chosen, the power and the authority which we have some time held.”

Noah Smithwick, a blacksmith in attendance, recorded the moment the Texas flag came down. Here is what transpired in that brief ceremony.

“Many a head was bowed, many a broad chest heaved, and many a manly cheek was wet with tears when that broad field of blue in the center of which, like a signal light, glowed the lone star, emblem of the sovereignty of Texas, was furled and laid away among the relics of the dead republic.”

The U.S. flag was raised, and the mood changed dramatically.

“We were most of us natives of the United States, and when the stars and stripes, the flag of our fathers, was run up and catching the breeze unrolled its heaven born colors to the light, cheer after cheer rent the air,” Smithwick recalled.

He tended toward that creature still common in Texas—the exceptionally proud Texan. Smithwick thought the star in the lower left corner of the U.S. flag should have been especially dedicated to Texas.

The exchanging of the flags made one statement. Jones made another: “The Republic of Texas is no more.” He made it politically true but never absolute because the republic lives on in the minds of Texans who still think of it as their country and their nation.